The Highest Gift: On Rambam’s Ladder by Valerie Kent

One of my not-so-secret pleasures is checking out other people’s personal libraries. I always find something there that intrigues me and makes me want to borrow it. One amazing coincidence was finding a copy of a book written by a high school classmate of mine in England in the library of the man from Connecticut I later married. I knew that this writer, Alan Coren, was a very good student who had gone on to become the editor of the satirical magazine Punch, but I did not know he had written a humorous book that would travel across the Atlantic and end up where it did.

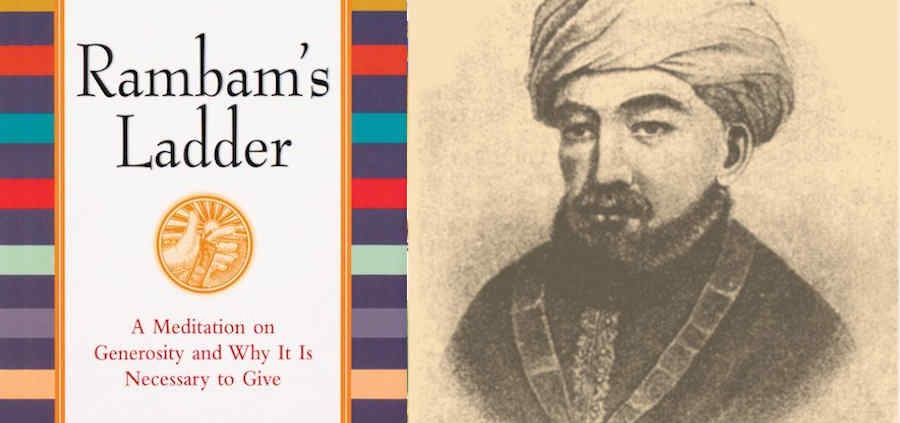

Anyway, I digress. What I want to write about is a book I found in the wall of bookcases belonging to my brother and sister-in-law when I went home to visit them this summer. They must have kept every book they had ever bought for their two children throughout the past 20-plus years. The shelves also contained their own their reading choices, many of which were best sellers. Tucked away among the fiction, I found this little gem of a book called Rambam’s Ladder. I read it avidly every night in bed when I couldn’t sleep and I brought it home with me to America.

The title had immediately caught my eye, since I vaguely knew that Rambam was another name for Maimonides, the Jewish scholar, mystic, and physician of the 12th century. I also knew that, among many other writings, he had constructed a “ladder of giving” with eight levels as a kind of stairway to heaven (although Jews don’t believe in heaven—let’s say a stairway to achieving righteousness). The lowest level of the ladder was giving money reluctantly and the highest level was giving someone the gift of self-reliance. In between there were various levels ranging from giving the proper amount, which included a discussion on tithing (i.e., one-tenth of one’s income); to give only after being asked to do so; to give before being asked but in such a way that the recipient feels a sense of shame for needing help; to give to a good cause but making sure you get the appropriate recognition; to give a personal gift to someone you know without revealing who you are; and the next-to-last step, to give to someone not known to you without revealing your identity.

Some of these steps may seem like splitting hairs—Maimonides was an expert in that. Even though he was kept very busy in his profession as a physician, he spent much of his life studying the Torah and explicating it to his fellow Jews, with all the many intricacies of fulfilling the law and the commandments. One of his most famous books was called Guide for the Perplexed. In a biography of Maimonides by the writer Sherwin B. Nuland, he was described as a “renaissance man” centuries before the Renaissance. He knew many languages, among them Greek, Arabic, and Hebrew. He had lived in Spain, Morocco, and Egypt, where he was the physician to a sultan. He was very familiar with other religions, particularly Islam, having masqueraded as a Muslim when his family lived in Spain.

Reading Rambam’s Ladder was an eye-opener to me. Though I did not consider myself a particularly generous person, I felt that I gave according to my means. I had a kind of conscience-satisfying regimen for giving. Every month I would send $50 to a different worthy cause and feel that that was my contribution to the needs of the world. Of course, if I had really thought about it, it certainly wasn’t tithing! Now, I don’t even do that. In the spirit of anonymity, I will refrain from saying what I do give, but rest assured, it is definitely not “generous.” In fact, lately, I myself have been on the receiving end of generosity, without even asking for help.

This book challenged me to rethink the subject of giving. The author interviews many people involved in the profession of philanthropy: millionaires, heads of foundations, fundraisers, people who receive recognition, people who prefer to keep their wealth quiet in case they get inundated with requests. Having worked in this area myself at various times, it brought back memories, not always pleasant, of an uneasy feeling about cultivating people with wealth in the hope of a donation. The author also explores her own feelings towards personal encounters she has had with needy people and her conflicted reaction to them at times.

Money is a difficult subject for many people to come to terms with. Sometimes we never seem to have enough, other times we have money to spare and can’t wait to spend it or give it away. For those of us uneasy about our giving habits, I recommend Julie Salamon’s book as a first step in understanding their own mixed feelings on this topic.

Valerie Kent is a part-time writer/editor/proofreader, who worked at Quinnipiac University in Hamden, Connecticut, for 26 years before retiring in 1997. She has been an Episcopalian, a Billy Graham convert, a Congregationalist, and a Jew, in that order. One thing she has not been is a Catholic.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!