When Jesus Met the Kings by Gene Ciarlo

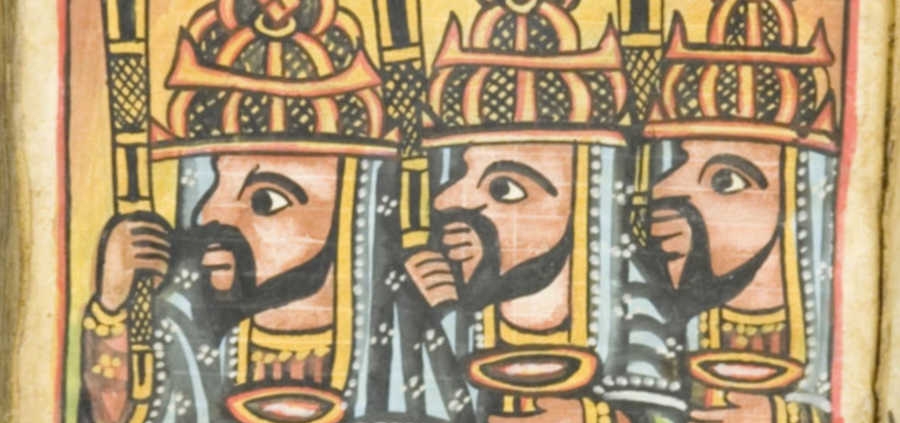

Every year without fail the Christmas season reminds me of my favorite Nativity poem by T. S. Eliot, Journey of the Magi. I’ve gone back to this poem time and again, and invariably it incites in me new reflections about the journey that is at the root of our Christian commitment and legacy. It is suggested by people in the know that the evangelist Matthew’s story of the three kings, the magi, is a tale told to juxtapose shepherds and kings, to announce that Jesus’s presence on earth was for everyone, rich and poor alike. It is a wonderful story worth pondering because it holds a lot of power for reflecting on the life of Jesus, the man and his mission.

Eliot’s poem is not one of his best nor is it particularly well known. But it contains within its simplicity some profound lessons. The poem begins with one of the kings reminiscing about their journey following the star: the terrible weather they endured, the camels, ornery and sore-footed, the “cities hostile and the towns unfriendly.” “At the end we preferred to travel all night, sleeping in snatches, with the voices singing in our ears, saying that this was all folly.”

But then the scene changes and seasonal harshness suddenly is transformed into a blossoming spring. Finally and in conclusion, the king recalls: “All this was a long time ago, I remember, and I would do it again, but set down this, this set down—this: were we led all that way for Birth or Death? There was a Birth, certainly. We had evidence and no doubt. I had seen birth and death, but had thought they were different; this Birth was hard and bitter agony for us, like Death, our death. We returned to our places, these Kingdoms, but no longer at ease here, in the old dispensation, with an alien people clutching their gods. I should be glad of another death.”

A journey is not a cut-and-dried deal. In a deal, as is religion to so many people throughout the world, you do this and God will do that. If you do not conform to the laws and strictures that God has imposed through his earthly representatives then beware, you’re playing with fire. To live rightly is a deal with God. On the other hand, a journey is work, it is a struggle, traveling rugged roads, living with uncertainty, often dangerous, draining, and uncharted. No maps; just following perhaps a star or a dream, a hunch, a guess, a hope—definitely a hope that there will be a springtime of enlightenment.

Listen to Yuval Noah Harari, an avowed atheist, noted historian, professor at Hebrew University of Jerusalem, offering his take on religion versus spirituality-as-journey in his 2017 book Homo Deus: “Religion is a deal, whereas spirituality is a journey. . . . If you obey God, you’ll be admitted to heaven. If you disobey Him, you’ll burn in hell. The very clarity of this deal allows society to define common norms and values that regulate human behavior. Spiritual journeys are nothing like that. They usually take people in mysterious ways towards unknown destinations. . . . For religions, spirituality is a dangerous threat.”

That final sentence strikes me like a bolt of lightening and speaks volumes. Spirituality is a threat to religions. Why? Because if you are on a journey searching toward an unknown, searching for meaning in your life, searching for understanding and enlightenment, then you will question your religion which has everything neatly set out as part of the deal—the doctrines and dogmas, the obligatory dos and don’ts. Catholics, especially, cannot do journey. After all, Roma locuta, causa finita: Rome has spoken, the cause is finished.

But let us get back to the poem, Journey of the Magi. The king contrasts birth and death. What of this death? Who died, and who was born? Something radical happened to him because of this Birth that he saw. After that, nothing was the same for him. Yes, the kings went back to their palaces and their riches, to the land and people whom they knew and who knew them well. But it was never to be the same. This king saw with new eyes, maybe a new heart and even a new hope. “No longer at ease here, in the old dispensation, with an alien people clutching their gods.” What a powerful phrase. He had a vision, made a discovery, a eureka moment, an enlightenment, and now nothing would ever be the same for him. He would be glad of another death which would open to him the light that he found in that Birth.

This poem reminds me so much of the journey of Christian mystics. Is this beginning to sound unreal and unrelated to our lives? After all, we’re just workaday people who don’t have time in our crazy world to deal with spiritual journeys and pie-in-the-sky, let alone mystical experiences. Bear with me a bit more.

If you have ever read the works of such people as John of the Cross or Teresa of Avila, you can see in broad strokes the tough way to finding much greater meaning in life than the vicissitudes of our daily grind here on earth. Like the kings in Eliot’s poem, John struggled through stages on his journey. Basically, writers over the years have named his spiritual progress a journey of purification, illumination, and transformation.

The rough-and-tumble camel ride into the unknown that the kings endured was not easy. In fact it was painful, not only physically but perhaps psychologically. But they struggled on with determination hearing the “voices singing” in their ears. It is the onset of the spiritual journey, and it is called purification. Then they arrived at a fertile valley, smelling of vegetation, with a stream running through it. They were not yet at their destination, but it was a peaceful and bucolic scene. In spiritual talk this phase might be called illumination, a glimpse of something good, a splash of cool water on the sweaty face. It is the beginning of vision; they begin to see.

They arrived and they were confused; birth and death, birth or death? Who died and who was born, perhaps even born again? John of the Cross called it a transformation, the unitive way, where there are no answers, just conviction about the world of spirit and life. Call it Buddhist nirvana if you are a Buddhist. And if you are a died-in-the-wool yogi you would recognize this as the Crown Chakra in kundalini yoga, the ultimate arrival point on the spiritual journey. You see that the format of John’s spiritual awakening is not peculiar to Christianity. It is universal and found in many religions, especially those of India and the East.

A conversion is in the works here. We might even call it a conversion from religion to spirituality. I think we all need to be converted from our passive, static, boring religion to a living and dynamic, rough-and-tumble spiritual life. Jesus was a wild man. No wonder he was finally murdered by the Romans. He was not fooling around with formulas and laws. In fact, his first job was to stir up the stagnant masses, his own people who fell into the habit of religion and were sold on the deal. And to think: it all started in a manger in Bethlehem, a great image that the gospel writer Luke chose to get his point across; from poverty and apparent nothingness to the grandest spiritual journey and awakening that humankind has ever witnessed.

Of course it has been ruined over the centuries. Following laws and rules is equivalent to stagnation and religion-as-usual. How is this different than the Judaism that Jesus condemned? We are victims of our human condition. That is what we do and we cannot help ourselves. But there is hope; we can wake up and start on the journey into the unknown. Jesus did this. I don’t think he knew what he was getting into. And by the way, whatever happened to the shepherds? I wonder if they ever joined the parade after the apparent Resurrection?

To get back down to earth, at my place of employment I asked one of my coworkers if he ever went up to worship at Weston Priory, the Benedictine monastery in Vermont, since he lives close by. He said yes—if he gets up early enough on Christmas morning he goes up there. He’s a good man, and his girlfriend is a gentle, kindly, soft-spoken, fine person. They are good people. I think there are many, many people like Alfie who may now and then ask themselves what it’s all about. This life is all too short, loaded with joys and sorrow, angst and anniversaries. We made it this far. What else is there? We can live in two different worlds, simultaneously. This world is just a chimera of things to come. But living in hope we must start the journey, or it will all end simply with a whimper when it should be a death that is indeed a new birth.

Gene Ciarlo is a priest resigned from active ministry in the Archdiocese of Hartford, Connecticut. He received an MA in Theological Studies from the University of Louvain, Belgium, and an MA in Liturgical Studies from the University of Notre Dame. After 10 years in the active ministry he returned to the American College in Louvain as Director of Liturgy and Homiletics. He now lives in peaceful and graceful Vermont.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!