The Spiritual Lessons of Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address by Douglas Lavine

Anything, I suppose, can spark a flash of enlightenment: a cloud, a tree, a bird. These precious moments sometimes issue from the most unlikely of places. One of those unlikely places, I submit, is a presidential address—to be more specific, Abraham Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address. No matter what your religious tradition—I am Jewish—or, if you have none, your belief system, this magnificent speech is worthy of study for a host of reasons, most significantly for the genuine humility and magnanimity it embodies.

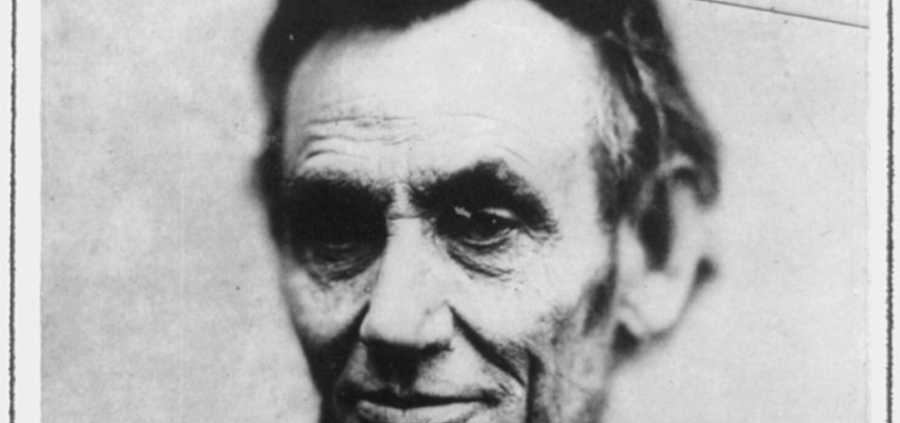

We don’t look to pronouncements by heads of state—or at least, I don’t—for spiritual succor, but this speech, unlike any other document of state I know of, enlightens, uplifts, and teaches. It does not inflame the emotions, it softens the heart. It is a literary masterpiece, biblical in its cadence, sublime in its sentiments. At the key moment of existential crisis in American history, along from the backwoods came this self-educated philosopher king, born 210 years ago on February 12, 1809, who embodied the most astute and enlightened political and ethical instincts in the center of a white-hot cauldron of death and destruction. To be sure, he was a man of his era, with some of the prejudices we now find offensive, but in his time, by any fair standard, he was enlightened.

Whenever I visit the Lincoln Memorial, I read the address. It is carved into the wall across from the more celebrated Gettysburg Address, close to the majestic statue of our 16th president. I usually read it out loud to catch its lyrical essence; it is meant to be heard as well as read. If you have never read the speech, I urge you to do so now, before reading on. (It is available at several places online, including the “100 Milestone Documents” series at OurDocuments.gov.) The speech is short (703 words), comprised of only four paragraphs, and, as with most of Lincoln’s writing, not a single word is wasted. Like most great lawyers, Lincoln had a knack for getting to the nub of things, the heart of his case. This speech offers as succinct and piercing an explanation of what caused the Civil War as you will find.

But what distinguishes it from other wartime speeches by a head of state is its utter lack of triumphalism, self-righteousness, or rancor. It has been dubbed “The Sermon on the Mount” because of its conciliatory, Christian tone. This was no “mission accomplished” speech, no self-congratulatory paean to the victor, by the victor. It was the opposite: a humble, unadorned statement by Lincoln of how he viewed the war in its larger, deeper sense. It does not bear the hallmarks of a speech by a self-righteous conqueror; it displays the sensibilities of someone who has known suffering, and who is searching to make sense of the extraordinary carnage the war brought.

To be sure, many of the thousands gathered to hear Lincoln’s remarks must have been deeply disappointed by its lack of vitriol toward the prostrate South. When it was delivered, the Civil War was winding down—it would end a mere five weeks later—and many in the North were relishing the thought of a harsh and vindictive peace which would punish the rebels and traitors who had torn the Union apart. They surely wanted to hear Lincoln demonize the South and figuratively dance on the corpse of the dying Confederacy. But he did no such thing.

History records that the day was rainy and cloudy at first but, as in a movie, the sun came out shortly before Lincoln began to speak. In the audience were ordinary citizens who had flocked to see the event, as well as reporters, politicians, reporters, ex-slave and abolitionist Frederick Douglass, as well as amputees—many of whom had lost limbs in the fighting. Also in the crowd, plainly visible well behind Lincoln in the most famous photograph of the speech, is John Wilkes Booth, who would assassinate him less than six weeks later on April 14, Good Friday.

Lincoln began his speech by stating that because the public had followed the events of the war, he saw no need to give an extended address, as he had four years before when he delivered his First Inaugural. Everything depended on the progress of the Northern armies, as the public knew.

He then reflected upon the dire circumstances facing him, and the nation, four years earlier. He had tried in his First Inaugural to reach out to the South, to avoid war, but even as he was speaking, there were insurgent agents in the city seeking to destroy the Union. “Both parties deprecated war,” he said, “but one party would make war rather than let the nation survive; and the other would accept war rather than let it perish. And the war came.”

The third paragraph is the heart of the speech. No summary or paraphrasing can do it justice. Here, Lincoln identified slavery, localized in the South, as the cause of the war, and noted that both sides had hoped for a quick and easy victory, while neither expected the war to last as long as it had. Then he stated, in famous words: “Both read the same Bible, and pray to the same God; and each invokes His aid against the other. It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces; but let us judge not that we be not judged”—a direct reference to Matthew 7:1 (KJV), and one of four Biblical references in the speech.

Lincoln continues: “The prayers of both could not be answered; that of neither has been answered fully. The almighty has His own purposes.” Here Lincoln acknowledges that human beings, with our limited vision and understanding of divine purposes, can never know the intentions of Providence. While all hope the scourge of war will pass, he states: “…if God wills that it continue, until all the wealth piled by the bond-man’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash, shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said ‘the judgments of the Lord, are true and righteous altogether.’”

Elsewhere, Lincoln directly references Matthew 18:7 (KJV): “Woe unto the world because of offenses! for it must needs be that offences come; but woe to that man by whom the offence cometh!” Insights such as these caused the theologian Reinhold Niebuhr to conclude that “Lincoln’s religious convictions were superior in depth and purity to those, not only of the political leaders of his day, but of the religious leaders of the era.” Niebuhr voiced his admiration that Lincoln was able to “put the enemy into the same category of ambiguity as the nation to which his life was committed.” The self-reflection and absence of triumphalism in the words of the wartime president, on the cusp of victory, is remarkable. Lincoln understood that the North shared some of the blame for slavery; its merchants had benefitted from the slave trade and many residents of the Northern states had simply averted their gaze from “the peculiar institution.” Lincoln rejected the tribalism and jingoism so many other statesmen would have embraced, and spoke in universal terms. The enlightened consciousness he displayed is stunning.

Lincoln finished the speech with some of the most famous words in American history: “With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for his who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and for his orphan—to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and a lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.” Note that his words are not restricted only to those in the Union. When Lincoln asked Frederick Douglass later that day what he thought of it, Douglass called it “a sacred effort.”

I majored in history in college, but I make absolutely no claim to be an historian, or, heaven forfend, a theologian. I am aware that the subject of Lincoln’s religious life and spiritual beliefs has been, and still is, the subject of study and by professional historians and Lincoln scholars. But I have no hesitancy, as a citizen, in asserting that anyone who reads the Second Inaugural Address reads the words of a highly evolved human being, a man of great humility, with a deep trust in Providence, and the highest measure of enlightenment—particularly for a head of state in wartime. We can only hope, as Americans, that our present and future leaders study Lincoln’s luminous words, meditate on them, and try to follow the awe-inspiring example he set.

The author, a lifelong student and unabashed admirer of Lincoln, resides in West Hartford, Connecticut. He urges anyone interested in this subject to consult Lincoln’s Greatest Speech: The Second Inaugural by Ronald C. White Jr. (Simon & Schuster, 2002), which was very helpful to him in the preparation of this article.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!