To Perform Is to Perfect: A Visit with Mother Dolores Hart by Michael Ford

In my many years of conducting interviews as a journalist, one is etched in my memory deeper than most. It took place in Connecticut in 2006. Not only was it a great story, to use the journalistic jargon, but the experience of making this documentary for the BBC World Service helped me understand more profoundly the paradox of vocation and how it is possible to integrate two, perhaps conflicting, passions within a deeper calling.

I was on the trail of Mother Dolores Hart, the prioress of the cloistered abbey of Regina Laudis in Bethlehem, and a one-time Hollywood actress who had starred with Elvis Presley. After making 11 films and becoming engaged, she left both Hollywood and her fiancée to follow God’s call. She later wrote a memoir of her experience, The Ear of the Heart, published by Ignatius Press in 2013.

Just like movie-making, radio programs are often recorded out of sequence, so the first interview with Mother Dolores took place in a New York hospital where she was receiving treatment for a nervous disorder. Then I was invited to join her in the car for her trip home, which gave me the opportunity to record a conversation about her life on Broadway as we were chauffeured past theaters where she had performed. Back in monastic seclusion over the course of two days, Mother Dolores spoke generously about her life as a contemplative and the struggles it had involved.

“I wanted the hound of heaven to cease,” she confessed. “I really didn’t want this vocation. But it wasn’t something that was a human decision. It was truly God’s call—and I knew that. I certainly did wrestle, not so much whether I made the right decision, but with whether or not I could handle what was being asked of me in the decision. The demands of the life of a cloister are so much different from when you have a check book in your pocket and can go anywhere you want as an actress.

“No one could possibly understand very easily what it costs to make that choice. My fiancé was wonderful in his capacity to accept what the Lord had asked of me and I truly feel he was a prince in his capacity to accept my decision. And we are still friends. I left behind license to gain freedom. People think something is free, but what they have is license, and then you eventually discover freedom as something very different from what you thought. Freedom is a matter of the heart. It is not a matter of doing what you want to do at any time you want to do it.

“My agent said: ‘You left Hollywood just at the right moment. You did it all in the films you did, so why do anything more?’ He was perfectly right. He said I would have kept doing it over again—only worse.”

Listening to the way Mother Dolores read Scripture during Mass—a master class in how to communicate the Word of God—it was evident that her dramatic abilities hadn’t been dulled. “I think we are always performing,” she said. ‘I think that ‘performance’ has a different meaning from ‘per-form.’ It’s more of an enriching word. We start out in life thinking of performance as an outer shell, something that we do that is apart from our inner capacity. Later we discover that to per-form is to perfect what is form in us. It’s to correct a form that is truly our own inner truth.”

She went on: “I think that to act is to do, and to constantly do what needs to be done. That was the lesson I learned from our foundress that, no matter how you feel, even if you have a 102-degree temperature, you go on the stage. That was the way she was. No matter how she felt, she did what needed to be done. I think that is the greatest lesson one can learn as a nun; that, no matter how you feel, your sentiments or your own sentimentality don’t get in your way. You do what needs to be done for another. It’s not so much of a discipline as the discipline that lends to love.”

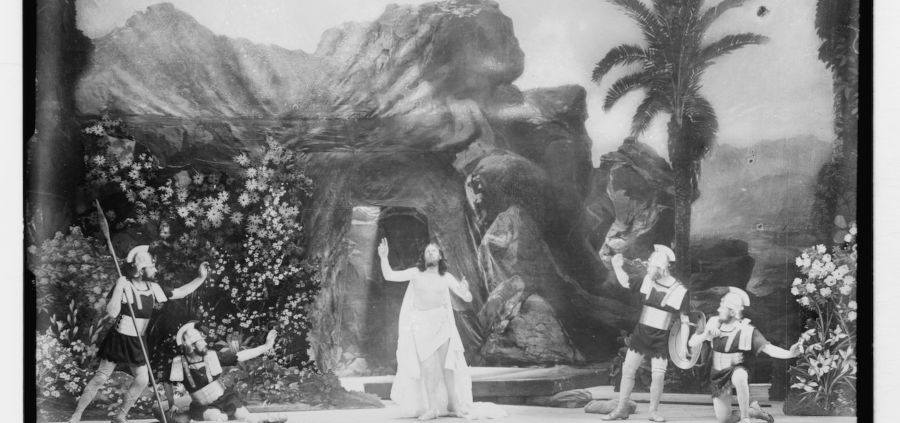

During my stay, I learned how Mother Dolores had introduced movie-making to the community. (Apparently she was as skillful behind the camera as she was in front.) I also discovered the theater she had helped build in the grounds, and how she had even set up her own production company, putting on annual shows with famous theatrical names.

“I really wanted to have a theater here because I think Saint Benedict would have wanted to advance the notion that theater is always something in the heart of the liturgy,” she explained. “They used to have plays before Matins so the idiots who couldn’t understand the Latin would know what was going on. I am still one of the idiots who needs plays to understand.” As we walked across the stage, where technical rehearsals were taking place for the next production, I asked how her two worlds came together in that context or whether it was, in fact, just one world for her. “It’s one world because I think the monastic theater brings a true holiness to the art form,” she said. “These players and musicians, and the persons who are bringing their crafts and gifts to bear, do that with a holiness that is truly the best of themselves. And that is truly what God is—the best of who we are.”

I wondered if her life would have been incomplete had she been an actress who hadn’t experienced the monastic or had she been a nun who had never embraced the theatrical. “I probably would have been suicidal on either ends of it—I’m serious,” she responded. “I don’t think that you can divorce yourself from who you are. I think that you have to marry your selves: if you try to be a nun without the truth of your whole being, or an actress without the fullness of your spirituality, you’re kidding yourself. You have to live to the fullness of the gift that God has brought in you. That you have to explore in prayer—and prayer tells you what the next step is going to be. Our chaplain is also our musician and musical conductor in our plays, so is he a chaplain or is he a musical conductor? He is both and he is also someone who brings to bear a coordinated truth of holiness for people who come and see that there is a left hand and a right hand that works in both ways.”

And that went for each nun in the community who might have led professional lives before they entered, some in high-powered positions. “You can’t just be a nun. You have to be a professional nun who knows what she is doing. I don’t think that I felt I was turning my back on Hollywood. I felt that I had to go into a deeper experience of something. I think that there is absolutely a continuity and, the older you get, the more that you see that your life is of a pattern. And if you can’t see it, you’re more grateful that you have a community that can.”

I asked whether the movement from the film studio to the abbey was one of illusion to reality or one from reality to a deeper reality? “I think you come from the illusion of the human soul and heart to the reality of God which for us is illusion because the transcendence of God for us is illusion,” she told me. “I have not seen what the Father has prepared for us—and for us that is a great illusion. We have no idea what that is going to be and we have to hang on pretty hard to keep our faith in that truth. I remember being so touched by the story of Pope Paul who, a few hours before he died, prayed for the gift of endurance that he would not fail God in the last hour, so one never has to take anything for granted. We must always ask for the gift of faith because it is a gift. It is not something we can demand, that we can conjure up or that we can create out of our human capacity to trick ourselves. It is a gift.”

As I was leaving, Mother Dolores gave me an envelope. Inside, not a signed Hollywood photo, but a picture of her as a young nun, along with a note thanking me for making the journey from England and for the hours of reflection on and off air. Like most of the interviews that are integrated into both my journalistic and spiritual pilgrimage, this was a once-in-a-lifetime experience. You are invited into somebody else’s world for a short time, write or broadcast your report, and then you move on, for that is the nature of the profession. But if journalism is your vocation rather than merely your occupation, the encounter is often something more.

Dr. Michael Ford lives in England, where for many years he was a broadcaster with BBC Religion and Ethics. An author of spiritual books and a retreat leader, he specializes in the life and ministry of Henri J. Nouwen. He maintains Hermitage Within, a website available at http://www.hermitagewithin.co.uk.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!