Truth in Their Own Time by Nancy Enright

Two quotes from the Holy Father:

“We have seen that it is unacceptable to say that the defeat of so-called ‘Real Socialism’ leaves capitalism as the only model of economic organization. It is necessary to break down the barriers and monopolies which leave so many countries on the margins of development, and to provide all individuals and nations with the basic conditions which will enable them to share in development. This goal calls for programmed and responsible efforts on the part of the entire international community. Stronger nations must offer weaker ones opportunities for taking their place in international life, and the latter must learn how to use these opportunities by making the necessary efforts and sacrifices and by ensuring political and economic stability, the certainty of better prospects for the future, the improvement of workers’ skills, and the training of competent business leaders who are conscious of their responsibilities.”

“In the secularized modern age we are seeing the emergence of a twofold temptation: a concept of knowledge no longer understood as wisdom and contemplation, but as power over nature, which is consequently regarded as an object to be conquered. The other temptation is the unbridled exploitation of resources under the urge of unlimited profit-seeking, according to the capitalistic mentality typical of modern societies. Thus the environment has often fallen prey to the interests of a few strong industrial groups, to the detriment of humanity as a whole, with the ensuing damage to the balance of the ecosystem, the health of the inhabitants and of future generations to come.”

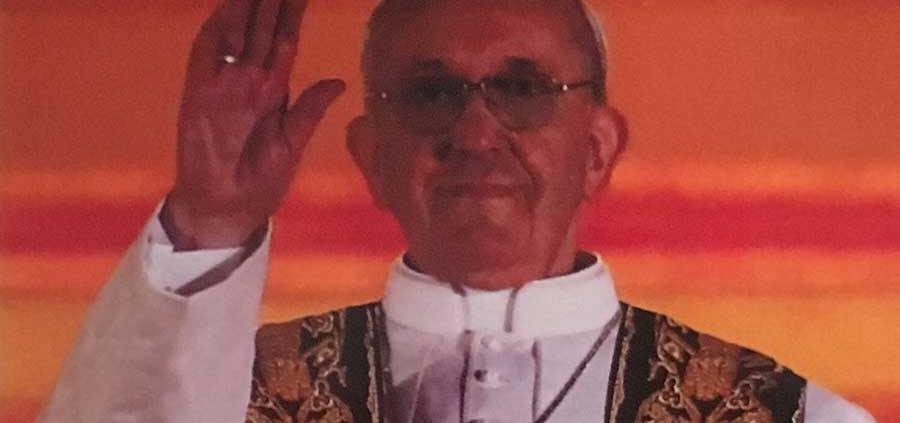

Whether they view him positively or negatively, most Catholics would likely guess that these provocative and challenging papal directives came from Pope Francis. After all, they deal with two subjects dear to his heart: economic justice coupled with concern for the marginalized, and respect and action to protect the environment as part of our spirituality. However, neither of these quotes is from our current Holy Father, but John Paul II. The first is from the 1991 encyclical Centesimus Annus, and the second a 1997 address to a conference on environment and health.

At Seton Hall University, where I teach in the English department and direct the University Core, we had a series of talks last year on the papal encyclicals, given by faculty from various disciplines. The Core Curriculum, for example, covered Ex Corde Ecclesiae, the 1990 apostolic constitution for Catholic universities. The College of Arts and Sciences presented on Fides et Ratio, a 1998 encyclical concerning faith and reason, with interesting proposals from a social scientist and a physicist. As I attended as many of these events as I could, during this past academic year, I have thought about papal encyclicals of the past more than I typically would do. This has been enriching in a variety of ways.

In our signature Core classes, we include Pope Francis’s Evangelii Gaudium and Laudato si’ among the first and second year’s optional texts, and many faculty, including myself, opt to teach them. However, as Francis points out in every one of his major writings, he is not writing in a vacuum or negating the position of his predecessors. Instead, he is building on what was spoken for their time and articulating it according to the vision given to him for our time. Being aware of the sense that any papal document must apply eternal truths to a particular historical situation, “nostra aetate” (“in our time,” as the title of the groundbreaking Vatican II statement on interreligious dialogue has it), can help us to avoid a polarizing and misleading comparison, particularly as regards John Paul II and Francis.

Often “conservative” Catholics will say the pope they “like” is John Paul II, and “liberal” Catholics will speak the same way of Francis. These two great leaders of the church become coopted by the polemics of our divided American political landscape. The truth goes much deeper, as a look at even just one encyclical, Centesimus Annus, indicates.

John Paul II, known as the pope who courageously took on the Soviet empire and helped to inspire its downfall, came of age spiritually under the domination first of Nazism and then of communism in his native Poland. His political charism grew out of that experience, and he spoke truth to the powers of his time. However, as the quote from Centesimus Annus above clearly indicates, he cannot be neatly labeled as an advocate of unbridled capitalism or, still less, a denier of climate change, unconcerned about the environment.

What would he have to say if he were alive today, when the safeguards that have kept capitalism in check, to some extent, in the United States have been diminished to such a degree that economic inequality has increased over the last 13 years? What would he have to say about the rapidly increasing devastation of the environment that has become more and more apparent since the time of his death? The quotes above suggest a direction his perspective might have taken in the 21st century.

In 1997 a close friend of mine, the late Jonathan Kwitny, published a book about John Paul II entitled Man of the Century. His book took the position that John Paul II was the pivotal figure of the 20th century, comparable to Gandhi or Martin Luther King Jr. as a peacemaker of epic stature. Today, though the 21st century is relatively young, we live in a world quite different from that in which John Paul II (who died in 2005) or Kwitny (who died too soon in 1998) lived.

Our current pope, Francis, is faced with problems that John Paul II addressed, but which have only continued to grow. Coming to the papacy from Argentina, having lived under a repressive government for many years, Francis brings some new insights to the same concerns addressed by his predecessor. (I do not mean to discount Benedict, but for the sake of comparison, I am focusing on the two papal figures who are most typically contrasted.)

The plight of the poor, the victims of what Francis calls “the idolatry of the marketplace,” is something that concerned him long before the beginning of his papacy. Known to go into the slums and for the simplicity of his life, Francis has merely carried these interests and personal habits into his much larger office. His is an entirely fitting response to the excesses of global markets and the widespread divergence between rich and poor of this century.

Similarly, Francis is only building on the concerns of both of his predecessors in his intense interest in the environment. As climate change causes damage at an accelerating pace each year, Francis’s encyclical Laudato si’ is a fitting call to alarm, based on a deep spirituality of ecology. Far from a new, “politically correct” interest, as if the pope were trying to fit in to concerns that are somehow “trendy,” Laudato si’ spells out how a loving concern for nature is rooted in our faith tradition and linked to social justice. We see this notably in the section on ecological debt, in which Francis argues that the richer nations who have caused the greater part of ecological damage owe debts to the poorer nations who are most affected by it.

Francis is speaking from a long and sacred tradition of reading nature as a second book of God, the Bible being the other. It is a tradition that goes back to Francis’s namesake, Saint Francis of Assisi, and, before him, the book of Genesis. Humans are created to care for the earth, not to use and abuse it, or eventually destroy it. Francis has built on an ancient tradition that leads right up to his two immediate predecessors, both of whom considered environmental concern an important spiritual commitment.

Reading past papal encyclicals may not be the habit of the average Catholic, and I do not pretend that it is a habit for me. However, even just a basic awareness of encyclicals like Centesimus Annus or the enormously important Rerum Novarum by Leo XIII (known as the originating statement of modern Catholic social teaching) will show us that many of the ideas of Pope Francis, articulated courageously and emphatically in his own exhortations and encyclicals, are rooted in the tradition of the church and the writings of his predecessors, as he so often has insisted.

What would John Paul II say if he could hear Francis unfavorably compared with him? No one can know the answer to this question, but I like to think that he might be saying, in his beloved Polish accent, “This is the man for the 21st century. He is the one expressing the truths of the Gospel to the challenges of your time.”

Nancy Enright holds a Ph.D. from Drew University. She is an associate professor of English at Seton Hall University and the Director of the University Core. She is the author of two books: an anthology, Community: A Reader for Writers (Oxford University Press, 2015), and Catholic Literature and Film (Lexington Press, 2016) and articles on a variety of subjects, including the works of Dante, Augustine, J. R. R. Tolkien, and C. S. Lewis. Her articles have appeared in Logos, Commonweal, National Catholic Reporter, Christianity Today, and other venues.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!