Breaking Hearts and Breaking Rules by Gene Ciarlo

If you break the church’s rules with impunity, after a while there won’t be any church left. It will have splintered into a million pieces with everybody doing whatever they like and choose to do. If the Roman Catholic Church is to remain viable and vibrant as an institution, the rules must be obeyed. It is a sociological principle.

A prominent woman who is known to have been married and divorced several times strides confidently up toward the altar as the priest is distributing Holy Communion. He knows of her infidelity and her alienation from the church, so when she arrives in front of him with outstretched hands, he refuses to give her the sacrament. She turns scarlet and buries her face in her empty hands. The gasps from the congregation are audible, as they too are embarrassed for her. What has just happened? The law has taken precedence over the spirit; a rule has become more important than a person and her shame, perhaps her contrition, perhaps even her repentance.

In one way or another this infraction is not uncommon, more so in our age of new enlightenment and individuation. It happens time and time again, not only regarding the sacrament of the altar but in many other tender and sensitive occasions when the institution must protect itself lest it fall apart from apathy and indifference to doctrines, dogmas, and rules which alone create order.

There is a significant flaw in that line of reasoning, however. In the embarrassing incident described it is not so much the authority of the church that is being put to the test; rather, it is traditional moral theology that ought to be under scrutiny. It is a matter of sin, grace, and reconciliation. From the Catholic Church’s point of view, you may not receive communion while you are in a condition of mortal sin because you have separated yourself from the grace of God and the communion of saints. You are no longer on a path toward heaven but in a state of damnation. In sum, to flout the rules on the reception of the Eucharist is to weaken the moral authority of the church and the developed theological history of sin, reconciliation, and grace.

This is the institution-centered approach to a response. But there is a different Gospel-centered approach that a person might find in the New Testament, interpreted from a holistic perspective. Call it the “Jesus mandate.” It goes like this: You have come to worship specifically because you believe in God and thus, wittingly or unwittingly, you have made yourself a part of this particular worshipping community at this existential moment. The fact of your presence is a sign that you are on a trajectory toward goodness and perhaps you have regrets for the misdeeds of your life. However, you have not availed yourself of the usual norms that the official church has established for reconciliation with the community at large. Your reconciliation is between you and your God.

A bit of history is in order at this point. In the earliest days of the church there were many, many communities of Christians who considered themselves followers of Jesus. They learned their lessons from one or another disciple of Jesus, perhaps a firsthand witness who had even written a text explaining his or her beliefs and practices. The community would therefore make known that they were followers of John or perhaps of Thomas or Mary. Their faith was in Jesus as Savior, but their beliefs and practices were according to a certain evangelizer whom they considered their leader, their bishop, so to speak, the one who oversaw the development of the fledgling Christian community.

In time, all of these Christian communities necessarily had to come together with greater unity. That is what happens for the sake of continuity in a growing community. In the fourth century it was the emperor Constantine who was responsible for the Nicene Creed; later his successor, Theodosius I, pronounced Christianity to be the religion of the Roman Empire. From a legal and institutional perspective those are historical facts, but theologically and practically it may have been Polycarp of Smyrna and Irenaeus of Lyons in the second century who actually got Christians to accept the same Gospel and teachings of Jesus. Irenaeus, while very tolerant of diversity among the various Christian communities, brought some sense of unity to them. It was a sociological as well as a spiritually unifying move on his part. We owe the 27 books of the New Testament largely to him.

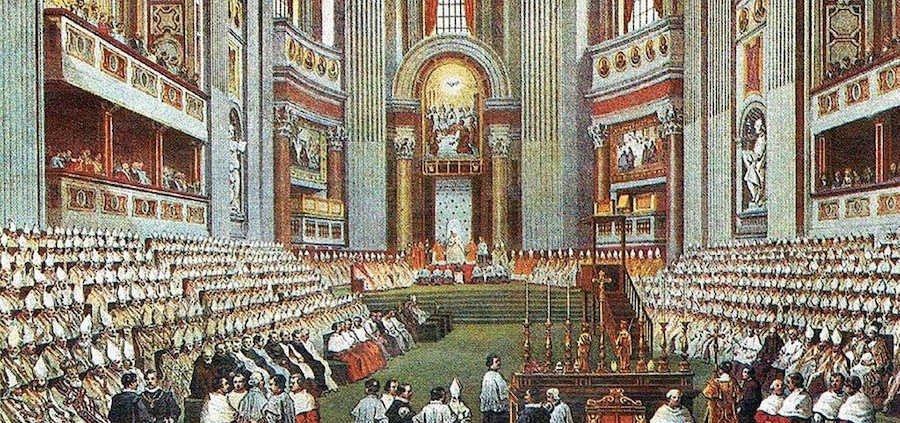

Institutional, sociological structures for the church were weak and minimal in those days. As numbers grew and the personal faith conviction of the newly initiated and baptized became more a matter of course than heart- and soul-felt faith in Jesus as Lord and Savior, the sheer numbers of faithful and not-so-faithful followers of Jesus burgeoned while quality was put to the test. The charisma that characterized the earliest days of discipleship receded into the background while hierarchical authority and the rule of law came into prominence. The Nicene Roman Catholic Church as institution was born.

The root of the question is: Can a sociological phenomenon as large as the Roman Catholic Church maintain unity and discipline, a common belief and practice, a collective agreement on teachings and expression of belief, and still remain faithful to the mind and spirit of its founder and center of focus, Jesus the Christ? That mind and spirit is one of compassion and mutual support, centered fundamentally on persons as individuals and in community. It is a juggling act to balance the law with the spirit of Christ. And in cases of conflict which are multiple, how is it to be resolved? In favor of the law or the Gospel mandates?

While recognizing blatant false teachings as heresy, the early fathers of the church were still flexible in their regard for individual communities of Christians and their founders. The communities that looked to John’s Gospel and the Gnostic gospels such as that of Thomas had great convictions about Jesus as one with the Father, Jesus as God, while other communities founded along the lines of Mark and Matthew’s gospels were less motivated by Jesus as God than by Jesus as a man among men, meant to be followed and emulated, truly a Son of God.

We go back to the original question: How is the church as institution kept intact while fostering the spirit of Christ? There will be conflict: laws are static and impersonal whereas religion of any sort has its focus on persons, their needs and aspirations, presuming good intentions inherent in their God-seeking inclinations. As fire seeks fuel, so the human heart seeks to go beyond itself into the world of spirit and life. The law kills; the spirit gives life, says Paul in his letter to the Corinthians. He too was assured that Jesus was God incarnate.

The example that I posed in my opening story presents a small, individual conflict between law and spirit. Today in our church there is the larger question of Christian, or should I say Catholic accommodation. For example, married priests in the Amazon region of the church, or various regional conferences of bishops and people composing their own Eucharistic prayers. Must there be only four “official” Eucharistic prayers? Can the same theology expressed in those four acceptable prayers be translated into the mind, spirit, and culture of native peoples without jeopardizing the unity of the Catholic Church? The concepts expressed in the Eucharistic prayers are universal. They can even be expressed in music and dance. Rather than simply calling it Christian accommodation, perhaps a better term might be cultural accommodation.

This is just one example of how the church might better accommodate itself to the great variety of cultures and traditions in our world without falling apart and splintering into hundreds of independent groups. The institution itself still needs greater renovation, proposed by Vatican II in several of its documents. Local conferences of bishops need and should have more authority over what happens in their dioceses without having to appeal to Rome for the final word. The Bishop of Rome can still be the first among equals. And now, going beyond the implementation of Vatican II, the laity ought to have a greater role in establishing the norms that will characterize the beliefs and practices of their particular communities.

I have simplified a very complex and multifaceted situation that is confronting our church at this time in its history. I have painted a picture with broad strokes, but hopefully it will open more doors and windows than those allowed by our present United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. The conference is inclined to retain the status quo for fear of schism within this branch of the body of Christ that we call the Roman Catholic Church. Why this inclination? There are multiple reasons; some are spiritual and sociological, while others are selfish and personal. A body of bishops can be as complicated and crafty as the US Congress. In sum, we ought to have more spiritual men and women who can speak the language of the Good News fluently in our conference of bishops. As it is, we have men who are fearful of rocking the barque of Peter centered in Rome; specifically, in the persons of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, formerly known as the Congregation of the Holy Office, and named, even before that, the Inquisition.

Gene Ciarlo is an ordained Catholic priest no longer in the active ministry. He lives and works in Vermont. He has been writing for Today’s American Catholic since the early days of its publication.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!