The World’s Parish Priest: A Review by Dale P. Faulkner

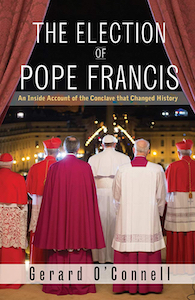

The Election of Pope Francis:

An Inside Account of the Conclave

That Changed History

By Gerard O’Connell

Orbis Books, 2019

$28 336 pp.

Doesn’t it seem that in many contested elections there’s a moment which catapults a candidate to victory? Think Richard Nixon’s sweaty brow contrasted with John F. Kennedy’s made-for-TV appearance, or George H. W. Bush’s “Read my lips: no new taxes,” or, regretably, “I’ll build a wall!”

Such a moment led to the election of Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio, Archbishop of Buenos Aires, as pope at the conclave of March 2013. But it was more sincere and prayerful than those moments, and it had a powerful impact on the cardinal electors. It is revealed together with a detailed, nearly minute-by-minute reportage of the proceedings and the upset victory that would refresh the spirit of the church and its sense of mission.

Gerard O’Connell writes with authority. He is an associate editor and Vatican correspondent for America magazine. He has covered the Vatican since 1985, reporting for several English-speaking news outlets. He and his wife, herself a Vatican correspondent from Argentina, befriended Bergoglio some years before. Relying on extensive inside sources developed over 25 years, O’Connell reveals, in large part, what happened before and inside the secret conclave. In fact, the couple were among the few Vatican watchers who predicted that their friend would become pope.

The book is neatly arranged in four parts: the resignation and departure of Benedict XVI, the vacancy of the see of Peter, the conclave, and early signs of the new style demonstrated by Francis. Within each part is a timeline which helps the reader grasp the essential facts.

Benedict took the world by surprise on February 11, 2013, when he announced his decision to resign. Most had forgotten that 10 years earlier, then Cardinal Ratzinger had been asked whether a visibly ailing John Paul II should resign. “Not him, but given that we live longer nowadays I can forsee that a future pope could resign,” he replied. Seventeen days after the announcement, Benedict’s resignation was formalized.

The second part of the book covers the 11 days between the end of Benedict’s papacy and the start of the conclave. Most of the cardinal electors had arrived in Rome. There were 115 of them, all under the age of 80, the cutoff for those eligible to vote for the next pope. Present too were 30 other cardinals all over 80, and thus ineligible to vote. They took part, however—some significantly—in the dialogues leading up to the conclave.

This period is marked by the questioning of what qualities and programs the next pope should have. There were dinners, meetings, and caucuses to delve into these questions. As a result, leading candidates emerged, although there was no clear choice. Cardinals Angelo Scola, archbishop of Milan, Marc Oulette of Canada, and Peter Erdo of Hungary were some of the names frequently heard. There was not much talk about Bergoglio, even though he had apparently finished a distant second at the conclave in 2005. Scola seemed to be at the top of most informal lists.

Between March 4 and 11, all of the cardinals present—electors and those not eligible—participated for six days in the General Congregations, pre-conclave assemblies. These sessions allowed the cardinals to speak on their respective views of what the church needed. The reform of the Roman Curia was a major topic. Bergoglio did not address the cardinals until the sixth day of the General Congregations. He delivered an unforgettable three-and-a-half minute intervention in Spanish.

Bergoglio focused on evangelization, citing it as “the Church’s reason for being.” He urged the Church “to go out from herself and to go to the peripheries.” When the Church fails to do this, he said, it becomes “self-referential” and gets “sick.” He concluded by reiterating that the next pope should help the Church to go outside itself, to the “peripheries.”

That speech was a, if not the, decisive moment in the lead-in to the conclave, a true turning point. Bergoglio “touched hearts,” O’Connell reports, “and many more cardinals began to see him as the candidate to succeed Benedict.” Boston’s Cardinal Seán O’Malley, who was sitting behind Bergoglio in the hall, recalled later, “Everybody had spoken about everything. But Bergoglio said something new and fresh.” Another witness said there was a “stillness” when he sat down.

The individual interventions are usually kept confidential, but Bergoglio’s remarks have been disclosed because Cuba’s Cardinal Jaime Lucas Ortega y Alamino asked him for the text that day. All Bergoglio had were some bullet points in his own handwriting. After the election, Cardinal Ortega was given permission by Francis to share the text with a wider public. A verbatim copy in English is set forth in O’Connell’s book.

The General Congregations ended on March 11, having identified the place of the church in the world and the principal challenges and tasks facing the church and the next pope. They also served to identify the kind of candidate who could best respond to these challenges.

The third part of the book covers the two-day conclave of March 12 and 13. Here the writer draws heavily on multiple sources, mostly anonymous because the cardinals are sworn to secrecy.

O’Connell reports that before the start of the conclave, several cardinals predicted there would be a wide spread on the first ballot. Indeed there was, with 23 cardinals receiving votes. Scola came in first with 30 votes, but this was short of what had been predicted by the Italian media. Bergoglio was a surprise second with 26, and Oulette followed with 21.

Because no candidate had the required two-thirds majority, the ballots were burned. Black smoke poured forth from the chimney of the Sistine Chapel, announcing to the world that the pope had not been elected.

The first vote showed Bergoglio to be a stronger candidate than many had initially believed. According to O’Connell, “He was known to be a very holy man, a humble, intelligent, inspiring pastor, devoid of ambition, who avoided the limelight, lived a simple life and had a passionate love for the poor.” O’Connell notes three additional factors that served in his favor: most Latin American cardinals backed him; he had shown his ability to inspire others when he gave his brief intervention; and he had support from Asians, Africans, and some Europeans.

On the next day, the second and third ballots showed a strong shift to Bergoglio. Many cardinals who supported other candidates turned to him. His gains continued through the fourth and fifth ballots. He was elected pope on the sixth ballot with 85 votes. Scola had fallen to a distant second with 20.

The fourth part of the book is limited to the first five days of Francis’s papacy. His earliest homilies are directed at the plight of the poor. We see how simply he chooses to live, eschewing the papal apartment and being driven in a modest car. O’Connell describes him as the “world’s parish priest” on the basis of just that handful of days, a description still apt as the seventh anniversary of Francis’s election draws near.

Dale P. Faulkner is a trial lawyer who practices in New London, Connecticut.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!