A Modern-Day Morality Play: On The Irishman by Leonard Engel

A brief survey of Martin Scorsese’s over 25 feature films and documentaries reveals at least two things: a rich variety of topics and characters, and an almost obsessive examination of individuals facing ethical, moral, spiritual, or loyalty issues (think Mean Streets, Taxi Driver, The Last Temptation of Christ, Raging Bull, Goodfellas, and Silence, to name a few). The Irishman, his latest film, encapsulates them all, becoming a capstone of the legendary director’s career.

Premiering at the New York Film Festival in September, The Irishman is based on Charles Brandt’s book I Heard You Paint Houses. The book evolved from several years of interviews Brandt conducted with Frank Sheeran (who died in 2003) and chronicles Sheeran’s rise in the Philadelphia underworld during the 1950s and ’60s. Sheeran claimed to be a close friend of Jimmy Hoffa and, in the interviews, confesses to killing him. This revelation caused a minor uproar among reviewers and crime historians when the book came out in 2005, and the film generated an even greater uproar when it appeared. In a post ranking The Irishman the best film of 2019 at RogerEbert.com, Brian Tallerico provides an incisive summary of the film’s reception:

It can be increasingly difficult to step back from controversy and the deafening din of social media to really look at a piece of art on its own terms. Many of the initial reviews of The Irishman seemed to focus more on Martin Scorsese’s comments about the . . . epic length of the film, the de-aging technology, how much Netflix spent on it, its historical veracity, or the specific line count of its female characters. While some of these issues are relevant to a discussion of the film’s quality, it does seem like the actual critical analysis of The Irishman is only now starting to come to the forefront of the conversation. And as we look deeper at this masterpiece, we realize how many layers there are to unpack, each one richer than the next.

I would like to “unpack” one of these layers based on a further comment by Tallerico: “The whole movie can be distilled into the flashback in which Robert De Niro’s Frank Sheeran remembers [as a G.I. in Italy during World War II] making German soldiers dig their own graves, wondering aloud why they keep digging when they know they’re just going to die.” In this flashback sequence, Sheeran stands above the hole and watches the soldiers as they dig. He suddenly orders them to stop, and as they climb out, he shoots them. He relates this incident to his new acquaintance, a mob boss named Russell Bufalino (Joe Pesci), who will become a friend and mentor for the rest of their crime-ridden days. Tallerico summarizes the remainder of the film: “We then watch as Frank Sheeran, like so many men, just keeps on digging his own grave for the rest of his violent life.”

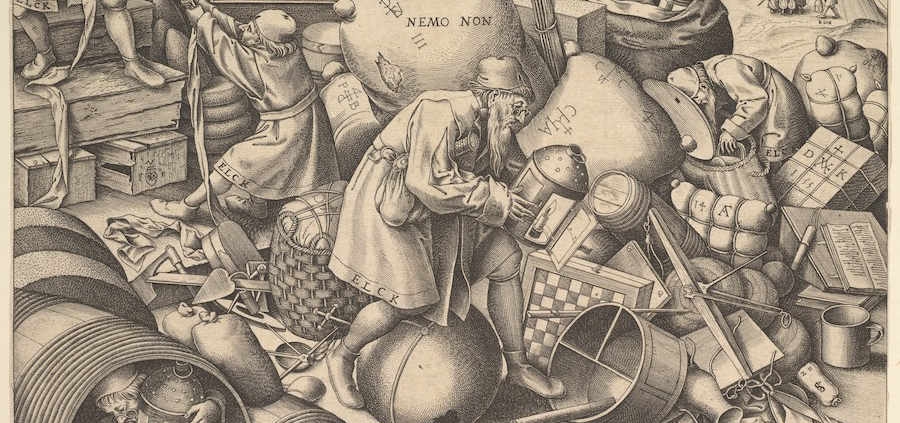

Sheeran’s “digging his own grave for the rest of his violent life,” can be read as a metaphor for the creation of a modern morality play. Morality plays grew out of religious mystery dramas in the Middle Ages and flourished in Europe in the 15th and 16th centuries. They usually featured a protagonist who represented an individual, a society, or humanity as a whole. Meant to provide moral guidance in a world of good and evil, they dramatized examples of various vices, personified by different characters—deceit, cheating, bearing false witness—which were then opposed by characters representing virtues, such as honesty or justice. The core idea of the morality play was that God, believing that humanity too easily succumbs to accumulating earthly riches, sends a strong reminder that death is all around us, and that sooner or later we will be forced to face that fact.

While most morality plays concentrated on evil, the anonymous 15th-century play Everyman became the best-known work of the genre because it focused on God’s power to help us overcome sin in its various guises. Scorsese, I believe, renders a contemporary version of this tale, but ironically reverses the traditional Everyman pattern by focusing on Sheeran’s gradual descent into the criminal underworld, never resisting or seeking God’s help. Going from stealing, to enforcing, to killing (the FBI estimates that Sheeran may have been involved in at least 25 murders), he eventually murders Hoffa, the kingpin of the Teamsters labor union, to whom he was a “loyal friend” at the time.

In an interview with Entertainment Weekly, Scorsese acknowledged Sheeran’s descent and the choice to depict it in detailed, visceral images: “the point of this picture is the accumulation of detail. It’s an accumulated cumulative effect by the end of the movie—which means you get to see from beginning to end [in one sitting] if you’re so inclined.” These words recall Edgar Allan Poe’s theory that the perfect fiction is one that contains a single idea, leading to a unity of effect and should be read in one sitting. The Irishman’s plot adheres to this: the controlling idea is one of moral choice, and Scorsese dramatizes with vivid images the choices Sheeran makes—choices that have devastating effects on others and leave him a pathetic old man, alone, waiting for death. (In another interview Scorsese claimed that the film is “all about the final days. It’s the last act.”)

The Irishman opens with the camera moving slowly down the hallway of a nursing home, passing communal rooms with small groups of people talking, playing games, and eating. At the end of the hall, we see the back of a resident in a wheelchair, sitting like a rock, with one leg partially extended; our first thought is that this person is dead. But as the camera slowly pans to the front and rests on the figure’s pallid, expressionless face, we see that he’s not dead yet, but his appearance suggests that he soon might be. There are other people in the room, but he is alone, staring into space; whatever is going on in his mind—possibly his past deeds—is about to be revealed.

Thus begins a series of flashbacks (including some flashbacks within flashbacks) as we see how these deeds play out in Frank Sheeran’s life. The journey is gradual, and, as Scorsese says, filled with “the accumulation of detail”—violent action resulting from Sheeran’s life decisions. Unlike Everyman, whose journey depicts resistance to evil, Sheeran embraces evil and thrives on the choices he makes, and his attitude and physical appearance reveal confidence and success. He is on track to achieve the underworld’s version of the American Dream as he sinks deeper into criminality.

In one early flashback, we see him driving a truck, delivering sides of beef to meat-packing plants, discovering how he can steal beef and sell it on his own. On a chance encounter, he meets Bufalino, a crime boss who controls the Philadelphia area, and Sheeran begins to do small jobs for him. Soon he graduates to enforcer, then to hitman. Through Bufalino, he meets Jimmy Hoffa (Al Pacino), begins working for him, and winds up as Hoffa’s bodyguard, signaling the union boss’s trust in him.

The film’s main flashback involves a road trip Sheeran, Bufalino, and their wives take to Detroit in 1975 to attend the wedding of Bufalino’s niece. However, this flashback is interrupted by earlier flashbacks including Hoffa’s arrest and incarceration and culminating in his return from prison and attempt to regain control of the Teamsters. Here Hoffa oversteps his power and is given a death sentence by the mob bosses. Since he’s a “loyal” friend of Hoffa and has access to him, Sheeran is chosen to do the hit—which he does during the wedding trip. This sounds grim, but Scorsese and screenwriter Steven Zaillian keep it moving and even humorous, almost slapstick at times.

Hoffa’s death scene is abrupt. When he arrives at a house for a scheduled meeting with members of the mob and finds no one there, he immediately senses trouble. As he turns to leave, Sheeran emerges from the shadows, shoots him in the back of the head, neatly arranges the body on the floor, then flees the scene. However, the aftermath of the crime is not abrupt. Hoffa’s “disappearance” appears to be heart-wrenching for Sheeran. At an informal family gathering when his daughter Peggy learns that her father has not called Hoffa’s wife, to whom Peggy was close, she gives him a ferocious, accusatory look and asks why he hasn’t. Her look reveals that she knows he’s involved, and she refuses to see him for the rest of their lives.

The denoument lingers and does not tie up loose ends, but leaves them fractured and scattered. We see Sheeran, practically in tears, talking to Hoffa’s wife on the phone; we see an older Sheeran with a cane, limping toward Peggy at work (she turns her back on him and walks away); we see both Sheeran and Bufalino in prison breaking bread and dipping it in what appears to be wine (a kind of communion, recalling a much earlier scene of camaraderie in a fancy restaurant where they dipped bread together). Back in the nursing home where the film began, we see Sheeran talking to another daughter about Peggy’s refusal to see him, and this daughter asking why he did the things he did. After an initial silence, he eventually mumbles something about protecting her and the family. To her pointed question—“Protecting us from what?”—he has no answer. Later, in his room, quietly talking to a priest, he appears to be to confessing; when the priest asks if he is sorry and if he ever thinks about the families he has affected with his actions, Sheeran’s response is no, because he didn’t know them. It is difficult to tell if he has real sorrow and has truly confessed, but the priest proceeds to give him absolution anyway.

The final image of Sheeran in the nursing home connects with the film’s opening scene, but now, as the camera moves away and we see him through the partially open door, we are left with the feeling that Scorsese and Zaillian have dramatized (through the “accumulation of detail”) the outer self of Frank Sheeran, but have rendered only a partial view of his inner life. Like the priest, we know little about his soul. What we do know is that he’s by himself, staring into space—maybe reliving his past, maybe not. We are left to draw our own conclusions, but these devastating, sad images of alienation speak volumes.

Throughout his life Frank speaks of how devoted he is to his family and how everything he does is for them. But now, like the lost characters in the medieval morality plays who couldn’t resist life’s temptations and went to their deaths empty and alone, with no faith or good deeds to rely on, Frank is bereft, stripped of his family and friends, left with nothing but thoughts of his deadly deeds. That is the ultimate question Scorsese and his team raise in this magnificent contemporary morality play: What has your life’s work amounted to? And how do you approach death?

Leonard Engel, Professor Emeritus of English at Quinnipiac University, lives in Hamden, Connecticut, with his wife Moira McCloskey. He can be reached at Len.Engel@quinnipiac.edu.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!