Reflections on Gratitude: Persevering through the Coronavirus Pandemic by Wally Swist

If we practice listening to our inner voice, and are disciplined in this practice, then we can also open ourselves to be able to listen to guidance. With our listening to guidance we enter into an inner quietude that is accompanied with an awe, a distinct sense of astonishment for being present in the moment, which is really how we began listening to our inner voice, which then lead to listening to guidance. When we are this present there is yet a fuller depth which we enter into, and that depth is that we can become awash in active gratitude.

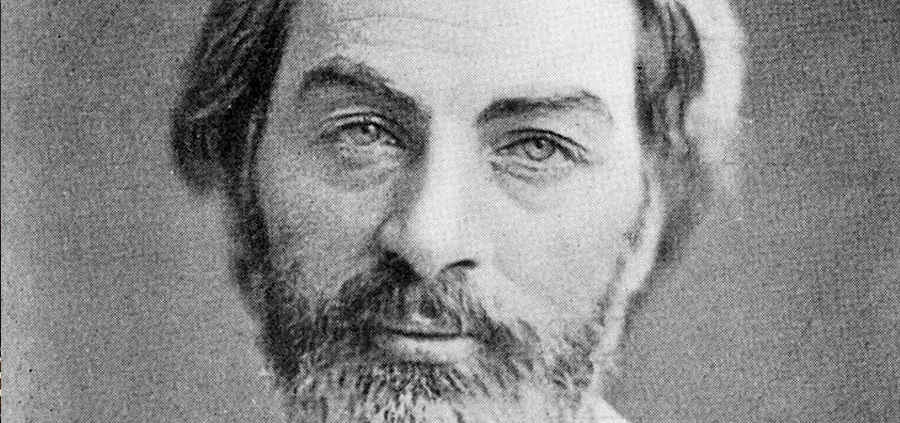

Active gratitude is the awareness of our interconnectedness with all things and with each other. However, in experiencing this awareness we also become more fully aware of our gratitude for everything and anything that we are touched by or that we, indeed, touch. And the list can be enormous. Walt Whitman and his endless lists within poems such as “Song of Myself,” in his visionary and ageless Leaves of Grass, comes to mind—certainly to the scrutiny of his critics. These critics may miss the inherent spirituality to be found in Whitman’s poetry, but despite their critiques, contemporaries of Whitman such as Richard Maurice Bucke—who not only knew Whitman and wrote a monograph on him, but is also known for his groundbreaking book, Cosmic Consciousness: A Study of the Evolution of the Human Mind—offer substantial claims that that the poet had broken through into an awakened state of being beyond a doubt.

We can begin simply by listing our gratitude during the coronavirus epidemic by what we miss: our weekly excursion to the local library, our interaction with our favorite grocery clerks, our not being able to walk through public parks or on the trails of nearby nature areas. Being shut in means we need to at least incrementally listen in to ourselves, “to the little ticking of the clock,” as Hercule Poirot from Agatha Christine’s The Clocks might say.

♦ ♦ ♦

If we can begin to practice active gratitude, we can start to access something altogether different, something that perennially enriches us, something that can become active within us—and that is awe and astonishment for each moment of every day. This practice can be described as finding the numinous in the everyday. To become aware of the ever-changing present moment in such a way offers nothing less than active gratitude, if not even a kind of magnetic sense of direction, a north star, a true north—and, yes, we can even call such direction a moral compass.

The idea of a “moral compass” brings to mind one of the most significant characters in all of English literature: Gabriel Oak from Thomas Hardy’s monumental novel Far from the Madding Crowd. There are some 19th-century writers who remain modern, and these can include Henry David Thoreau, Emily Dickinson, Walt Whitman, and most certainly Thomas Hardy. Far from the Madding Crowd is a novel that regards the awareness of gratitude and the active practice of it, and it is, indeed, one of the great ones.

Gabriel Oak is a formidable character who embodies a moral compass. Hardy introduces us to him as a sheep farmer, one who is thriving, the owner of a large flock, in full competence of himself and of the knowledge of the land on which he lives and loves, on a ledge above the ocean. When he sees the ravishing Bathsheba Everdene, who is working on a local farm with a relative, the spark of eros is struck within him, and he proposes to her. In keeping with her fierce independence, she refuses him; however, this is not the end of their relationship with each other but only the beginning.

As we might be blighted in whatever myriad ways during the coronavirus pandemic, Gabriel Oak loses all of his sheep one night when one of his sheep dogs (he has two named George, and this one was the crazy one) drives all of his sheep out of their pens then herds them off the sea cliffs into the breakers below. Despairing but not quite distraught, Gabriel Oak moves on to a large farm, which by now Bathsheba Everdene has inherited, and ends up saving a large barn from burning down due to an accidental fire beginning in one of the hay lofts. Bathsheba offers Gabriel a job, and the story continues on from there, with Gabriel practicing care and love for Bathsheba: at one point, he saves an entire harvest on her wedding day from an oncoming storm by tying tarps over the stacks of grain; at another, he perseveres with her through a doomed romance, which he had predicted would be wrong for her.

Gabriel Oak is sturdy in his moral compass. He never deviates from his course, not even once, but perpetuates in his practice of active gratitude. He may not have had Bathsheba’s hand in marriage, nor her promise of that happening someday, yet he stands firm in his conviction to love and care for her, to make sure the farm is succeeding enough that he might even think of leaving it after her doomed romance is finally finished. It is only then that Bathsheba comes to the conclusion that Gabriel is someone whom she does love, a man strong enough not necessarily to tame her but to ride alongside her and to endure to be her equal—as well as she being his. Gabriel Oak is a necessary hero in our age of a sheer lack of heroes; moreover, he is a practioner of active gratitude since he does not lament what he doesn’t have but opens himself to the level of the heart and becomes aware of his interconnectedness with all things and to all people, which is, if anything, a Whitmanesque notion and vision.

♦ ♦ ♦

The eminent psychologist and psychiatrist Carl Jung, who is the founder of analytical psychology, stated at the end of his long life that he thought he had made it as far as the fourth chakra of the Hindu system, which is the heart chakra. Of course, this is the level of the heart, and this is also the practice of active compassion. Joseph Campbell, a noted expert of comparative religion, calls this activating of the fourth chakra moving “out into the marketplace as Christ did” on a daily basis. This involves practicing active gratitude for our interconnectedness with all things and all people, especially during these trying and challenging days of the coronavirus epidemic. Even within the confines of our own homes, with open hearts, we might progress in this practice. We might see this moment as an opportunity to become more evolved as human beings, to veritably advance our souls toward a growth of awareness and consciousness that is, above all, our birthright.

For each of us who moves forward in this way, there must surely be a light that blinks on for each consciousness that is raised for everyone across the globe. And to imagine not only our own practice of active gratitude preparing such an event, but that our collective active gratitude could possibly change the world, is more than enough for us to consider beginning our practice, unhesitatingly, not just sometime today but at this particular moment—this one that is so rich in such nascent and distinctly wondrous world of possibilities.

Wally Swist’s recent books include The Map of Eternity (Shanti Arts, 2018), Singing for Nothing: Selected Nonfiction as Literary Memoir (The Operating System, 2018), and On Beauty: Essays, Reviews, Fiction, and Plays (Adelaide Books, 2018). His book A Bird Who Seems to Know Me: Poems Regarding Birds & Nature was the winner of the 2018 Ex Ophidia Press Poetry Prize and published in 2019. His other books include The Bees of the Invisible (2019) and Evanescence: Selected and New Poems (2020), also from Shanti Arts of Brunswick, Maine.

Wally Swist blows me away with his encompassing ability to reach far and wide for examples and writers who boost his premise as well as send me back to the library with thoughts of rereading or finding those books I’ve either forgotten or never got around to reading. Who else quotes Hercule Poirot? Years ago I visited my hero T.E. Lawrence’s hideaway cottage in Dorset. “Clouds Hill” is now a rentable National Trust Writer’s Cottage and stark as ever. Reading up afterward I learned that he often visited Thomas Hardy who lived nearby. And our world gets smaller. Well done, Wally.