Faith in the Incarnation by Ed Burns

One could write about the Incarnation for pages and pages and still not exhaust the meaning and wonder and the astonishing good news that God reveals to us in this great mystery. “About Christmas, we know more than we can say,” writes the theologian John Shea in his book Starlight. “The intuition of good news exceeds our ability to spell out what it is.” The story of Christmas is not just about the story of Jesus. It is our story, too. It is the story of ourselves, the story of who we are.

I know a woman who had experienced several severe losses in her life. In the course of approximately one year, she had undergone a divorce, her father had died, and her adult children had moved out of state. On Thanksgiving Day of that same year, some friends invited her to spend Thanksgiving with them and their family. She was pleased with the invitation and readily accepted. As they sat down at the table for their meal, she looked about at the others who were gathered there, her friends, their children and grandparents. She said that she suddenly became overwhelmed with a great sense of sadness as she remembered other similar meals which she had shared with her own family in the past. She asked to be excused from the table momentarily and removed herself to an adjacent room, where she quietly and privately began to shed tears of sorrow and grief. However, at this point, one of hostess’s children, a five-year-old girl, came into the room looking for her. The little girl noticed that her guest was crying, and she asked her why. The woman explained briefly that she felt sad because she missed her father and her children and that she was feeling all alone. According to my friend, this little five-year-old looked at her and in all innocence said, “Well, that’s okay; you don’t have to cry anymore because you still have me!”

I really like that story. In fact, as I think about it, I realize it is a wonderful description of Christmas. Of course, the major difference is that in the story of the Incarnation, it is another child who speaks to all of us, the babe of Bethlehem, the Son of God and the Son of Mary, who now looks up at us and says, “That’s okay. You don’t have to cry anymore because you still have me.” Later on, when this child of Bethlehem has grown into an adult and is facing his own impending death, he says the same thing to us in different words: “I will be with you all days, even to the end of the world.” John Shea describes this pledge on the part of Jesus as an expression of the “non-abandoning love of God, a love of God that will not let go of any human person.”

The story of the Incarnation, our story, in which we claim to believe that God became human, is so simple, so awesome, and so amazingly good that it is all too easy to dismiss it as wishful thinking or as a sentimental fantasy. A prominent French theologian once wrote: “As I join in worship and prayer with fellow believers, a mood of astonishment sometimes overtakes me as I listen to what is being said and taken for granted, things which all human calculation left to itself would judge preposterous nonsense.” Perhaps our greatest temptation is to give the miraculous story of Christmas a passing acknowledgement and then, shortly after the holiday season, to get back to the “real world.” To quote from Shea’s Starlight again, “Christmas is not just one day of naivete and idealism in a year of unrelenting realism. Christmas is a day of the real, in a year of illusions. If we wake up on Christmas morning (really wake up), we may realize we have been sleepwalking the rest of the year.”

If we think about it for a moment, this fundamental claim of our Christian faith does sound preposterous, or, if you will, literally unbelievable. There are many who would regard Christianity to be exactly that: unbelievable. Christianity has always been met with a certain amount of skepticism. In his book about Christian practices and education, author Craig Dykstra expresses his concern that even our churches have sometimes become infected by a practical atheism, or what he describes as a “nasty suspicion that nothing real corresponds to the language of faith.”

We hear all around us at this time of year the language of faith: “God so loved the world that he sent his only-begotten Son”; “Behold, a virgin shall conceive and bear a son, and his name shall be called Emmanuel, which means, God with us”; “And the angel said to them, ‘Be not afraid, for behold, I bring you good news of great joy.’” But does anything real correspond to this language? Are these words expressing truths that we can stake our lives on? Is there any substance, any grounding, beneath these expressions? Our gathering in our churches on Christmas day is a witness to the fact that the answer is yes. These things we say and sing about the Incarnation are the truths of our lives. Many important and profound implications for our lives flow from our belief in the Incarnation of the Son of God. Faith in the Incarnation enables us to always have within us a cause for hope, even in the most hopeless of human situations. And faith in the Incarnation roots us in a source of ever-increasing joy that no one will be able to take from us.

Shea says something that may sound almost heretical in certain circles: “Christmas is not for children!” (How awful!) But he quickly appends, “Christmas is for the ever-rejuvenating child in each one of us. I cannot shake Christmas, because I will not admit that growing old and growing weary are the same thing. We can grow old, and not only not lose wonder, but increase it. We are not meant for gloom, and when there is news that the world is more, wondrously more than our poor minds are able to hold, we cannot resist the invitation.”

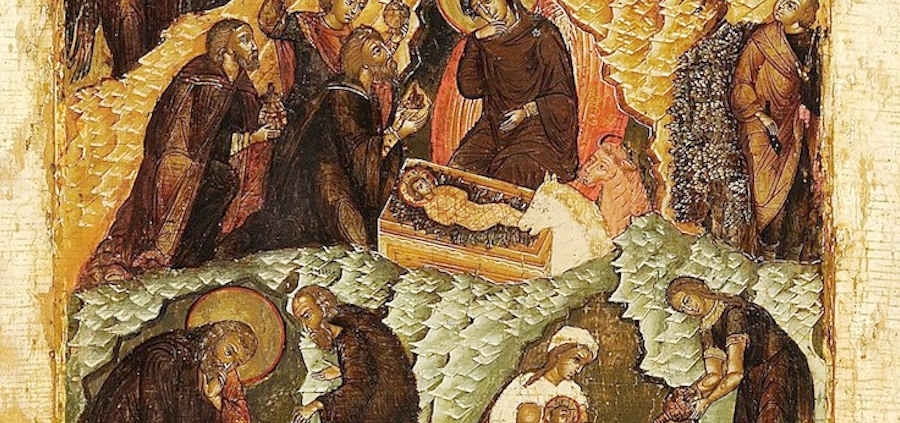

The reality that our God brought about at the moment of the Incarnation can no longer be confined to a single day, or a single place, or a single innocent child lying in a manger in Bethlehem. That reality now encompasses and extends beyond all of human history. In the moment when Mary gave birth to Jesus, God gave birth to a transfigured universe, a new creation, a redeemed humanity that has now become sanctified by the intimate presence of God in all of human life. Our Christian faith in the Incarnation invites us into a great mystery, something almost too good to be told, something about who we are. In the mystery of Christmas, I come to know myself as capable of God, as desiring God. I come to know God as the secret of my own heart, as the mystery of my own heart’s desire. For those of us who have been graced by the gift of insight into this mystery, Christmas will always be a source of unending hope and joy.

Ed Burns is a licensed marital and family therapist living in Litchfield, Connecticut, where he maintains a private practice treating individuals, couples, and families.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!