Losing Our Way to Nazareth by Gene Ciarlo

The world, nation by nation, people by people, from time immemorial, has never been completely satisfied and of one mind with its politics. Has there ever been a utopian state? Saint Thomas More wrote about it in his 16th-century sociopolitical satire, Utopia, focusing on a utopian island, self-contained, perfectly harmonious, with everyone in agreement, living in a common culture and understanding of how things ought to be. Of course it’s all incredible. That is why it is satirical; it could never happen.

I want to bring us back to another aspiration with the hope of utopia. It happened with the birth of Jesus. Let us look at the drama that Matthew and Luke portray in their stories of his birth. (Just to give you a heads-up on where I am going with this, if we want to place it in the context of our nation in the 21st century, Matthew leans Republican and Luke definitely favors the Democrats. It becomes more obvious in the stories they tell individually about the birth of Jesus.)

Marcus Borg, the great Episcopalian scripture scholar, has suggested the idea in his small but powerful book, Meeting Jesus Again for the First Time. I take up where he leaves off in describing the stories of the pre-Easter Jesus of history, over against the post-Easter Christ of faith.

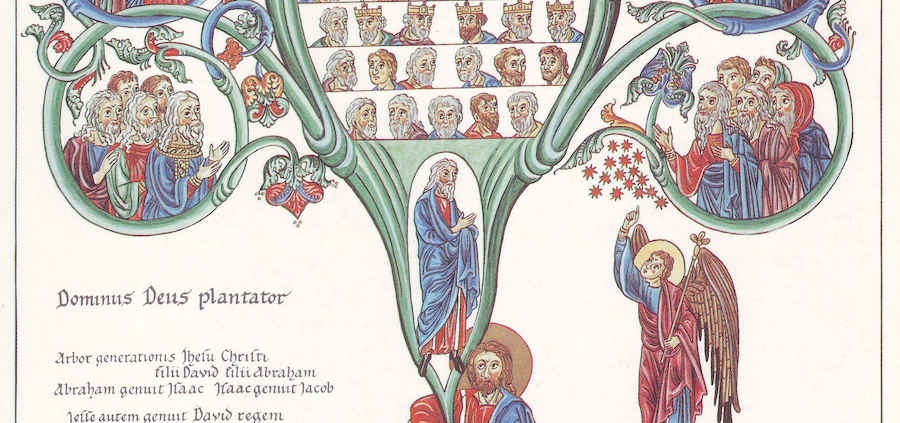

Matthew starts his gospel story with a genealogy, going back to Abraham, the father of the Jews. He notes the kingship of David and traces the lineage of Jesus through the kings of Israel. Luke, on the other hand, in his genealogy goes back to Adam, the father of both Jews and Gentiles. He too highlights David, tracing Jesus’s genealogy not through the kings but through the prophets of Israel. The kings of Israel and the prophets of Israel are traced, respectively, up to the birth of Jesus. We’re seeing a picture forming already. Let us open up the stories as they continue.

In Matthew’s birth narrative, which is totally symbolic and completely nonhistorical (as is also Luke’s narrative), there are wise men from the East seeking the king of the Jews. The story gets complicated and dangerous when they go public and ask, “Where is he who has been born king of the Jews, for we have seen his star in the East, and have come to worship him?” They find him in Bethlehem. Herod gets wind of the story. Bad news for Mary, Joseph, and Jesus.

Meanwhile in Luke’s story of Jesus’s birth, there are shepherds in the fields watching over their flocks by night. The next thing we know there are angels, singing, and lots of emotion pouring out among the shepherds as they make their way to Bethlehem. You know the rest. It is a tender scene, humble, poor, simple, quiet, peaceful, and loving. The shepherds too are looking for a king, but kingship in Luke’s story is not nearly as pronounced as it is in Matthew’s story. Kingship doesn’t normally begin in a stable.

Here we see the different emphases according to two different accounts of Jesus’s birth. The wise men in Matthew are seeking the king of the Jews. Shepherds, the marginalized people who receive the message first in Luke’s gospel, find an infant who in time becomes a radical social prophet. And the question is asked in Matthew’s gospel, “What manner of man is this?”

The world has always known the rich and the poor. There, in the two gospels that tell about the birth of Jesus, we see the extremes that have defined our sociopolitical world for millennia. These two extremes have caused great trouble throughout the ages of humankind.

♦ ♦ ♦

The mantra of the Clinton campaign back in 1992 was “It’s the economy, stupid.” The words have become famous because they speak to most people who think of their pocketbooks first when they think of a president, a congress, a political party, and America as the land of opportunity. And what does opportunity mean but an education, a good job, one that pays well and offers personal satisfaction?

But there is another voice, a contrary political and societal voice, the voice of Jesus when he said, “The poor you will always have with you” (Matt. 26:11). That reality is with us almost daily, or we would not be getting robo-callers or real-life solicitors asking for money, nor the hundreds, maybe thousands of NGOs and other organizations seeking funds because without help they would not have the resources they need to keep reaching toward their goal, whatever that goal may be. The poor are always and will always be with us.

Meanwhile, on this earth that Jesus trod once he went public with his message was a society overwhelmed with the poor. It was not the world of the high priest of Judaism nor of the Roman vassal, Herod the Great. It was the world of the apostles and people like the blind and the lame, the deaf, the leprous, the dying and the dead. They were the poor, and Jesus the man who we know historically (as distinct from the mystical Christ of faith), is the one who lived in Nazareth until he left home to elevate to a new level the lives of the common people, taking up where John the Baptist left off.

Jesus’s message was not about how to get rich. It was about how to live your life to the fullest as a man or woman of God. It was not “the economy, stupid.” His main message as a historical figure, not as the one who saved us from sin, was compassion. Today we might use another term; perhaps empathy is a good word. It is definitely not sympathy. Sympathy is sharing someone’s sorrow. Empathy is putting yourself in someone else’s shoes and being one with them in what they are going through in their lives. Empathetic people suffer a lot because they feel other people’s pain. I might suggest that Jesus suffered more in his life than he did in his death. It was a different kind of pain, not physical pain. His was more heartbreaking than body-breaking.

In my life I have met very few people who were truly compassionate. In other words, I have met very, very few Jesus-like people. That is not a statement of negative criticism. I have met many, many people who try to live lives of compassion. The common cliché is that life is a journey. We certainly hear that enough, but what does the journey entail? It is a passageway, narrow and tortuous, toward compassion. And compassion is unity, being one with each other. That is what we do not have in our world, and today that is what we do not have in our country.

I am attached to the Jesus of history. Although I may believe, I cannot talk to the Christ of faith who died on the cross to save me from eternal damnation. The gospel of John is a theological powerhouse of the Christ as Redeemer and Savior. I do talk daily to the Jesus of Nazareth, the one who lived his life for other people right here on earth, the one who lived for the poor and ultimately died for the poor. I always say “Jesus”; I never address him as Christ. That’s my style. Leaving aside the threat of sounding political, I think I may be a Democrat if looked at from that point of view. I am a shepherd man, not a king admirer.

At this moment, as I write these words, striking me are the lines of a great poet, William Wordsworth:

The world is too much with us; late and soon,

Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers;—

Little we see in Nature that is ours;

We have given our hearts away, a sordid boon!

. . . For this, for everything, we are out of tune;

It moves us not. Great God! I’d rather be

A Pagan suckled in a creed outworn . . .

Christian evangelicals? Roman Catholics? Christians, Jews, Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists? We have lost our rootedness in the compassion of not only the social reformer, Jesus, not only in the Messiah, the Christ, but in the great Prophet Mohammed, Buddha, Shiva, Krishna, and all those revered as exemplars of compassion. We have created our own political gods, and they are not like the one born among us to show us how to live, how to be compassionate, Yeshua ben-Yosef.

Gene Ciarlo is an ordained Catholic priest no longer in the active ministry. He lives and works in Vermont. He has been writing for Today’s American Catholic since the early days of its publication.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!