The World as It Is by Ed Burns

Some time ago I met with an elderly gentleman at Catholic Family Services, where I was then working. This person had recently experienced the death of his wife, to whom he had been married for almost 50 years. He was grieving her loss deeply, and when I spoke with him, he was on the verge of tears. It was evident that he was in a great deal of emotional pain. “If only I had the answer,” he said to me, as if his suffering and confusion would be taken away with some sudden insight into his implied question of “Why? Why did this happen?” I had no such answer, although I wished I could have relieved him of his distress.

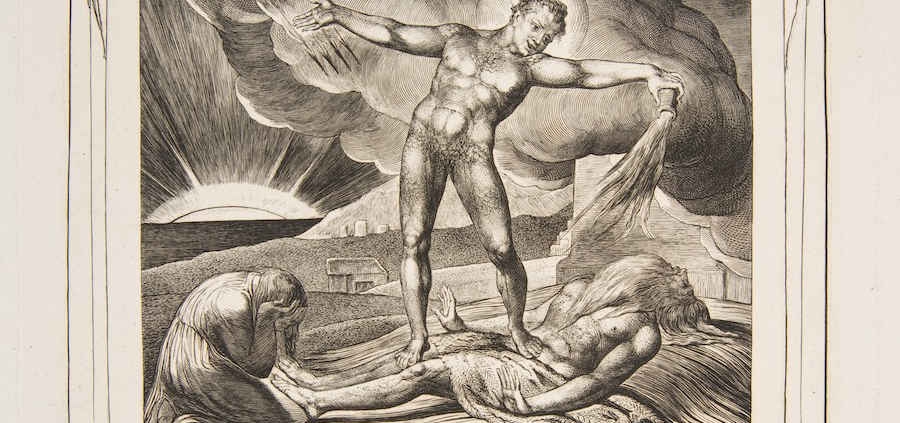

I thought of this encounter as I recently read a passage from the book of Job. The passage did not have much in the way of consolation to offer the reader. In fact, it was quite bleak in its outlook. The author of the book of Job struggles with the perennial question of the problem of evil. He challenges God to provide some kind of answer to its mystery: Why is there suffering and death in our lives? Why does God allow injustice and the powers of darkness to prevail over us? Why do bad things, horrendous things, happen to good people?

Fr. John L. McKenzie, a courageous and sometimes acerbic Catholic scripture scholar, now deceased, once wrote an essay on the book of Job in which he expressed one of the most insightful comments about the book’s meaning and message:

At the risk of being more subtle than the author, I think he meant to say that the faith which will carry one through such a crisis as the crisis of Job is not possible without a religious experience, an experience of God which gives one a new insight into the reality of God which is not conveyed by conventional wisdom in any age. Job has been granted such an experience. It may come as a disappointment to the reader of the dialogue because it does not convey to him the insight which it did to the author. The reader may be looking for an answer to the speculative problem of evil, and the poet had no answer to this. In fact, no one has given an answer to the speculative problem, not even Jesus. What the poet believed he had found and what Jesus proposed was not an answer to the problem of evil but a way in which one can live with it. Rarely does one meet a man or a woman who has learned to live at peace with evil. When one does meet such a person, one knows that one has encountered wisdom, which recognized God in the world as it is.

Two things trike me about these words of Fr. McKenzie. In the first place, he says that the book of Job gives no clear and satisfying answer to the problem of evil. He goes on to say that there is no such answer to be found to the speculative problem of evil, either in the Old or the New Testament. The answer, that is to say, the only proper response to the problem of evil is not to be found in some rational explanation; rather, it is to be found in a way of life lived, a way of life most clearly exemplified in the person of Jesus, imitated throughout the centuries by holy men and women who have endured varying forms and degrees of suffering and who have managed somehow not to lose faith in their God.

The God in whom these men and women believed and clung to, however, was not just any God. And certainly it was not the abstract God of the philosophers, a God remote, immutable, intangible, seemingly indifferent to what goes on with us, a God who watches us, as the popular song goes, “from a distance.” It is hard to be in love with a God who merely watches us from a distance. It is hard to wrestle with, or challenge, or question that kind of a God, as did the author of the book of Job.

On the contrary, the God of Job and the God of Jesus was not simply a distant observer of the human condition, but rather one who was and is a participant in our history and involved in our human condition, up close and personal. The God of the book of Job and of Jesus is a God of passion, irony, and affection; a God who can be as jealous as a spurned lover, and as comforting as a nursing mother; a God who loves us in our frail, fragile, and imperfect humanity. The God whom Job and Jesus reveal to us is a God of surprises, a God of compassion and humor who is invested in us, in what we do, think, feel, and suffer. Our God is a God who can get mad at us, and then turn around and withdraw his own anger and forgive us. “His mercy endures forever,” we say. God knows all about us, and loves us anyway. It is this biblical God, not some reasonable and logical God of our intellects and philosophies, whom we claim to believe in, and whom we have been instructed by Jesus to call Abba, “Father.” This is the kind of a God who can command our trust and loyalty even when bad things happen to us.

The other thing that strikes me in Fr. McKenzie’s reflection is the comment about how rare it is to meet a man or a woman who has learned the wisdom of recognizing God in the world as it is. Sometimes we strive with all of our might to get away from the world as it is. The elderly gentleman whom I referred to earlier wanted to do just that: His wife had died. He was suffering from his loss, really suffering. He wanted to get away from it. He wanted his pain to cease. He wanted his wife back.

We react in all kinds of ways when we run up against the hard edges of the world as it is. Sometimes we try to soften our vision of our experience of the world to protect ourselves from its harshness by sentimentality, or cynicism, or flights into fantasies of our own imaginations where things can seem more manageable. “Humankind,” says T. S. Eliot, “cannot bear too much reality.” And so, at times, we try to avoid reality rather than looking at it straight in the eye.

But Jesus did look reality straight in the eye. He was not sentimental. He was not naive. He was not cynical. He knew what was in the heart of man, and he knew what was in store for himself if he continued to reveal and proclaim the kingdom of God. But he did continue. He continued to be invested in our humanity because our humanity and our human condition had now become his own.

Jesus values our humanity. It is us, in our humanity, that he has come to redeem—not some ideal humanity, not a utopian humanity, not the humanity of the “beautiful people,” but our humanity. “The good news [is] located at the center of our humanity,” as the Jesuit author William F. Lynch has written; elsewhere, he says, “It will always be the human as we know it that will be redeemed.”

Jesus was a healer. He healed Peter’s mother-in-law, the blind, the crippled, the lame. He healed people in their bodies and in their spirits, in their human bodies and their human spirits, calling them and us always to the fullness of life, to the fullness of our own humanity. He is precise on this point: “I have come that you may have life and have it to the full.”

It is important for us to realize as people who believe that Jesus is Lord, that our vocation is to become fully human, not angelic, but human. We are not there yet, but that is our vocation. In the fourth century, Saint Irenaeus of Lyons put it quite simply: “The glory of God is the human person fully alive.”

There is, then, no longer anything alien between our humanity and God. This is an astounding statement, but it is precisely the good news we claim to believe. Jesus eliminated the chasm of separation that prevailed between ourselves and God when he became human, one of us. We can refuse this vocation and the friendship that Jesus has created and offers between ourselves and God. But we cannot deny that the offer is there. For us to recognize that the offer of friendship between God and ourselves is there, always and everywhere, in spite of everything that the world may bring upon us, is to recognize God in the world—as it is.

Ed Burns is a licensed marital and family therapist living in Litchfield, Connecticut, where he maintains a private practice treating individuals, couples, and families.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!