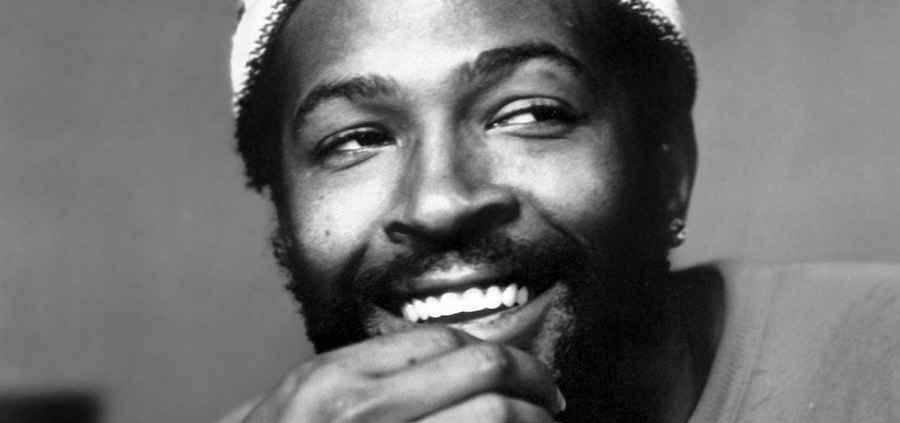

“We’ve Got to Find a Way to Bring Some Loving Here Today”: Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On” at 50 by Chris Byrd

“God is writing this album, Smoke.” That is fabled singer, songwriter, and producer Smokey Robinson recalling what his good friend and fellow Motown recording artist, the late Marvin Gaye (1939–1984), said while working on his masterful album What’s Going On. Released May 21, 1971, What’s Going On ranked first in Rolling Stone’s 2020 survey of the top 500 albums of all time. Such rankings are always debatable, but this album deserves its rarefied standing among the pantheon of great records.

Groundbreaking stylistically, conceptually, and thematically, unapologetic in its Christian viewpoint and distinguished by its trenchant and prescient social justice commentary, What’s Going On is “more poignant today then when it came out,” Robinson said in a recent CNN special. Exploring the influences that shaped it, what differentiated it artistically, and its still relevant messages, we uncover the album’s enduring cultural, social, and spiritual impact as we commemorate its 50th anniversary.

The singer’s relationship with his Pentecostal preacher father, also named Marvin, overshadowed everything Gaye did. Often unemployed and with a penchant for wearing women’s clothing, Marvin Sr. was a brutally abusive father and husband. The night Gaye died on April 1, 1984, a day before his 45th birthday, at the Los Angeles home he shared with his parents, he intervened when his father was beating his mother, Alberta. With the gun his son had purchased for his own protection, Marvin Sr. shot his namesake to death.

Prior to making What’s Going On, Gaye’s younger brother Frankie’s stories about serving in Vietnam convinced the singer to change his musical direction. Fellow Motown artist and Four Tops’ founding member Renaldo “Obie” Benson brought Gaye’s vision for his protest record into sharper focus. While Benson’s group was on tour in San Francisco in 1969, in a scene uncannily reminiscent of what Black Lives Matter protestors experienced in the summer of 2020, the singer observed policemen beating Berkeley students in an abandoned urban lot called People’s Park. This incident prompted Benson to reflect: What’s going on? Why are the cops beating these kids and why is our country sending our kids overseas to fight?

Gaye added some lyrics to Benson’s along with instrumentation and recorded what became the album’s title track. Iconic Motown founder Barry Gordy warned Gaye, however, that “your career will be ruined” if he released a protest album. Gordy scrupulously cultivated his artists’ public images. A quality control board furthermore assured records balanced pop and R&B, appealing equally to urban Black and suburban white teenagers. Gordy worried that a record about war, poverty, substance abuse, and environmental desecration would alienate more traditional listeners.

According to CBC music critic Pete Morey, Motown creative department executive Harry Balk championed the title song and convinced vice president of sales Barney Ales to distribute 100,000 singles of it on January 17, 1971, behind Gordy’s back. It became the fastest-selling single in the label’s history.

Motown’s first concept album, What’s Going On didn’t feature the standard Motown sound. Heavy on congas and bongos, percussion drives the mix of jazz, blues, and funk. Drawing upon his experience singing in his father’s Pentecostal church’s choir, Gaye infuses several numbers with a gospel feeling and message. The layering of the vocals also gives What’s Going On a distinctive sound. Gaye recorded two tracks of lead vocals, which were inadvertently combined, enabling him to become his own background singer. The various tones and the eclectic mix of sounds make listeners more receptive to the songwriter’s intricate suite of challenging messages.

The chorus of voices on the opening and titular song announce the setting as a house party for a freshly returned Vietnam veteran. “Father, Father,” Gaye sings, “War is not the answer. For only love can conquer hate.” That’s pure Dr. King. But it’s also a plea to the artist’s own dad.

Unusual for a pop recording then, the revelatory track “God Is Love” reflects Gaye’s explicitly Christian vision. He defiantly sings, “don’t go and talk about my father. God is my friend (Jesus is my friend).” The songwriter describes believers’ reciprocal relationship with God in deceptively simple terms: “All he asks of us is we give each other love.” But “when we call on Him for mercy, He’ll be merciful.”

Love and mercy, the song “Right On” relates, require empathizing with poor people. Implicating himself, the songwriter indicates how greed, consumerism, and ambition block our empathy. “Some of us were born with money to spend” and “races to win,” while “some of us feel the icy wind of poverty blowing in the air.” On a cold winter’s night in Detroit when your walls are thin and you don’t have enough heat, that devastating and evocative phrase gets to the heart of poverty’s cruel sting.

“Inner City Blues,” What’s Going On’s final track, closes the album with an edgier beat and adds an element to the songwriter’s cure for societal ills: changing our funding priorities. “Rockets, moonshots,” Gaye sings, “Spend it on the have-nots.” With spending on the Vietnam War undermining the domestic War on Poverty, the songwriter urges investing the $28 billion ($328 billion today) earmarked for the Apollo program into antipoverty efforts. The phrase “defund the police” might strike some as ill considered, but anyone urging us to think more creatively about how to employ our resources should identify with these lyrics.

The album’s opening number focused on a returning veteran, but the closing one emphasizes the multiple challenges experienced by the families left behind: “Bills pile up sky high / Send that boy off to die.” Representing just 11 percent of the population, African Americans nonetheless accounted for 23 percent of US combat troops fighting the war, reflecting the adage that militarism is racism applied. Families struggling to build sustainable futures understand the meaning behind the saying “Every bombed dropped kills twice.”

Urging listeners to see “what’s going on,” Gaye constantly interchanges the words father, brother, mother, and sister throughout in the album. What’s Going On is finally a cry for greater solidarity and more love among the human family.

Following What’s Going On, Gaye returned to recording the erotically candid songs, such as the great tunes “Let’s Get It On” and “Sexual Healing,” with which he’s typically identified. But he didn’t release another album with What’s Going On’s import. It endures, for its artistry certainly, but also because the issues Gaye addressed in its songs sadly remain germane.

With its calls for more creative social spending and its pithily redolent lyrics such as “trigger happy policing,” What’s Going On has been recently embraced by Black Lives Matter advocates. The issues may be the same, but the BLM movement is one example of what’s changed for the better in 50 years. In the ways they didn’t in 1971, more people are resisting the destructive forces the singer called us to oppose. We observe other signs, to paraphrase the songwriter, of people coming together to find their power and strength, such as fast-food workers demanding fair wages and undocumented workers trying to reclaim their stolen ones.

Gaye’s song cycle continues to inform our resistance to war and militarism, poverty, racism, police brutality and gun violence, and climate change. No matter what form our resistance takes, the lyrics from the title track that held true 50 years ago hold even truer now: “we’ve got to find a way to bring some loving here today.”

Chris Byrd writes from Washington, D.C. His work has appeared in America, Sojourners, and the National Catholic Reporter.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!