A Provocation for Change: Reimagining the Parish Community with Eileen McCafferty DiFranco by Michael Centore

Eileen McCafferty DiFranco has always identified as a rebel. Even as a child, the author, activist, and co-pastor of Saint Mary Magdalene Community (SMMC) in Drexel Hill, Pennsylvania, was constantly reading and questioning authority figures. These practices carried over into her relationship with the Catholic Church. Though she was raised in the church, she stopped going as a teen. She found that the priests of her Philadelphia parish never seemed to address the critical issues of the 1960s such as racial tension or the Vietnam War in their homilies; consequently, she felt ideologically and spiritually distanced from her church community.

When she was moved to return to the faith as an adult, Eileen first joined a new Catholic parish, then left to explore Lutheranism. Eventually she found her way to Saint Vincent’s in Philadelphia, which was run by the Catholic apostolic society of the Vincentians. Here, she says, she encountered a true gospel witness as parishioners and staff alike modeled the teaching of “Love your neighbor as yourself.” Saint Vincent’s “changed her life,” and she soon began to invest herself in the community and participate in numerous parish committees.

Even in this welcoming and inclusive environment, there were limits on what priests could speak about. Homilies were silent on the topics of women’s ordination and gender equality, two issues particularly important to her. Rather than grow passively more frustrated, she took action by getting involved with the Women’s Ordination Conference (WOC), a grassroots organization that advocates for feminist voices and women’s full equality within the Catholic Church. She allied herself with the Southeastern Pennsylvania chapter of the WOC, began contributing to its newsletter, EqualwRites, and eventually joined its Core Committee.

Around this time, the mother of one of Eileen’s son’s friends suggested that she might look into the Lutheran Theological Seminary in Philadelphia. This woman had attended the seminary herself and spoke highly of her experience. Eileen says she was drawn to the seminary as a way to “learn the language” of the church “to figure out why it was so oppressive of women.” Harking back to her childhood practice of reading voraciously as a way of understanding the world and interrogating its systems of authority, she threw herself into her theological studies beginning in 2000. She ended up doing a full Master of Divinity (M.Div.) track, which required 30 courses. She notes that she wasn’t the only non-Lutheran student at the seminary, and counted several fellow or former Catholics among her classmates.

Eileen left Saint Vincent’s in 2005, again seeking a more outspoken ministry and a more engaged parish presence. She migrated to a small faith community with a few others, but there were some issues with leadership and it ultimately did not work out. A core group splintered off and reformed as Saint Mary Magdalene Community, an Intentional Eucharistic Community (IEC) that cultivates an open, democratic leadership structure and a common priesthood in which all members have equal status in liturgical and social life.

In the meantime, Eileen continued her studies at the seminary. When a colleague told her that “God wants you to stand outside” and work for change in the Catholic Church, she began to discern her vocation. In 2006 she was ordained by Roman Catholic Women Priests (RCWP), an international organization that prepares, ordains, and supports women who are called to the priestly ministry. RCWP ensures there are “guardrails” in place for newly ordained women priests, so they are released into their new roles with proper training. Eileen was a member of the first group of women priests to be ordained in Pittsburgh that year. She soon experienced pushback from the church and received a letter from a local bishop claiming that she was “a scandal.” Undeterred, she tried to begin a dialogue with the bishop. He agreed to meet with her but would not discuss women’s ordination. Later, he submitted her name for excommunication.

Such pressure would be enough to demoralize most, but Eileen pressed ahead on the path where God was leading her. She completed her M.Div. in 2007 and set about acquiring clinical pastoral experience. She relates one funny story from this time: while she was doing ministerial fieldwork, she once was given a “clergy shirt” to identify her as a priest. The shirt was purple, which she thought nothing of—until others in her group pointed out that this was the color officially worn by bishops!

Newly ordained, her faith bolstered by the intellectual rigor of the seminary, Eileen turned her attention to nurturing the nascent Saint Mary Magdalene Community. Among her first tasks was to prepare a liturgy and lectionary that better reflected the spirit of the group. She worked with others to remove sexist language from the sacramentary, the book of prayers the priest uses to lead the Mass, and excised the vocabulary of traditional atonement theology with its off-putting image of a God who demands retribution for human sin. Monarchial language, too, such as describing the divinity as “reigning” over humanity, did not ring true to the group, so they found alternate ways of expressing their devotion.

Eileen says that in preparing the readings for their services, the group focused on a simple question: “What can we do to get us through the week?” The lectionary includes stories of women that are not featured in traditional Catholic Masses, such as the “bent-over woman” of Luke 13:10–17, the deacon Phoebe, and the midwives of the first chapter of Exodus. In the process of assembling the readings, Eileen observes, “we were growing into who we were as a community.”

Today none of the SMMC priests use the standard sacramentary. Instead, they assemble their liturgies from various sources, including gnostic writings and books such as Hal Taussig’s The New New Testament, a compendium of traditional and newly discovered texts. In defense of this approach—and as she makes clear in the excerpt from her book below—Eileen notes that early Christianity was actually a mosaic of multiple Christianities, each engaged in the prayerful work of articulating its beliefs. A “singular theology” would only emerge hundreds of years later, shaped by political concerns as much as religious ones.

Around 2009, Eileen was informed by a member of the church hierarchy that she had “excommunicated herself” along with anyone else who had even attended her ordination ceremony. She was then told that women’s ordination was a “graver offense” than the clerical sex abuse scandal because it “struck at the heart of the faith.” While individual priests have been supportive of her, church leadership on the whole has been antagonistic.

SMMC began by meeting in people’s homes, but soon required more space as they grew organically. This is common of many IECs, which arise from parish closures, priest shortages, theological and ideological differences, and other factors. Eileen thinks of them as the “island of the lost toys”: collectives of people who still wish to pray, serve, and celebrate the sacraments together, and who want to remain rooted in the Catholic and gospel traditions, but who “just can’t do it anymore” in the context of their home parishes. Some IEC members cite the sex abuse scandal as their motivation for migrating from the institutional church; others crave a more hospitable and welcoming environment than they find in traditional parishes, a greater emphasis on issues that the institutional church has been slow to act on, such as anti-racist initiatives, or a deeper engagement with the local community, particularly the underserved.

IECs “empower people to take things into their own hands,” Eileen says. They allow for more intimacy and dialogue between members of the community, who are encouraged to share their responses to homilies, and are home to many former priests, nuns, other religious. Some visitors have “culture shock” when they visit IECs, which are much more democratic and egalitarian than institutional churches. Eileen describes them as “almost Quaker-like, but with more liturgical elements.” Even with the best intentions, not all IECs succeed. SMMC originally had two satellite communities. One fell by the wayside while another remains active in New Jersey.

Eileen sees IECs as the inevitable response of a Catholic Church that is “growing smaller and smaller.” With the rise of the internet, news of the institutional church can spread faster, and people are more aware of its missteps and internal contradictions. Eileen observes that as bishops align themselves with political projects, they alienate many believers, especially urban dwellers. This was evident in the US Conference of Catholic Bishops’ recent threat to deny communion to President Joe Biden—a campaign that several bishops, including Robert McElroy, have opposed for its “weaponization” of the Eucharist.

“Younger people crave authenticity,” Eileen explains. “They are less interested in the majesty of the Catholic Mass and want a church that works for justice.” She mentions Father Gregory Boyle, the Jesuit priest and founder of the gang-rehabilitation program Homeboy Industries, as an example of church figure younger people are drawn to. Yet “we cannot just exchange men for women priests and expect everything to be OK. The whole story [of the church] needs to change. It is not the story Jesus wrote, but the story that powerful men wrote.”

Eileen’s experience led her to write How to Keep Your Parish Alive in 2017. The original inspiration for the book came after she worked in an area of inner-city Philadelphia known as “the Badlands” and saw many Catholic parishes close in the 1990s. “There were no provisions for care, no imagination in thinking about ways to keep the parishes open,” she remembers of the time. Church officials “could have done something, but they did nothing.” Evangelical churches soon filled this spiritual vacuum, and the Catholic Church lost a precious opportunity to serve marginalized communities as it moved out into the suburbs.

After learning that 40 percent of parishioners do not return to the church once their parish closes, Eileen wondered why the hierarchy was so willing to leave those most in need. She wrote her book as a way to “inspire and empower” those affected by shortsighted parish closures. She advises parish members to band together and “continue doing what you’re doing” regardless of what the bishops might say. “There is a way to do this,” she encourages, citing communities such as Spiritus Christi of Rochester, New York, as good models. Above all, have faith and don’t be afraid to start small: as an IEC grows, people’s talents will be recognized by the community and they will step into the roles that need to be filled.

Humankind is awakening to two related insights: a recognition of our global interdependence, and an understanding that sustainable futures will be created through small-scale, decentralized, bio-regional communities. Within the context of the church, IECs are, in their own way, transforming both of these insights into action: they provide the seedbeds of prayer where the aspirations for a transnational, trans-cultural solidarity can take root, and they foster organic connections between people in an open, democratic, nonhierarchical way. In the excerpt from How to Keep Your Parish Alive that follows, Eileen gives a well-founded synopsis of the theological grounding for IECs at the dawn of Catholicism’s third millennium. ♦

How to Keep Your Parish Alive

How to Keep Your Parish Alive

By Eileen McCafferty DiFranco

Emergence Education Press, 2017

$14.95 157 pp.

(Excerpt from Chapter Seven, “Tectonics”)

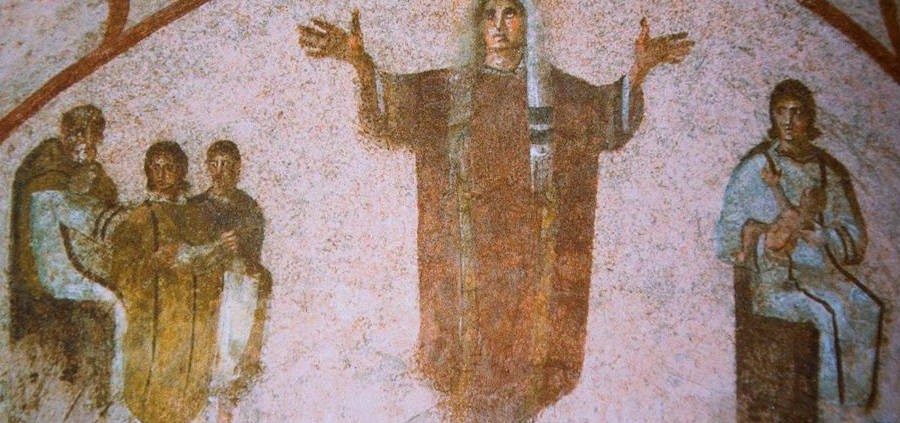

For those who wonder if small church communities are a viable way of worshipping God, it must be remembered that small faith communities have an historical precedent. The early Christians continued to observe the Sabbath on Saturdays in the temple after the death and resurrection of Jesus, per the Acts of the Apostles. They also met in house churches, shared a common meal to remember Jesus, and read from whatever holy book they might have had since the New Testament would not exist for another three hundred years or so. Contrary to Scripture, which often lists “thousands” of converts at its beginning, Christianity was a very small affair that did not separate completely from Judaism until the late first century. Like the people of today, it took time and prayer for people to leave the comfort of their respective faiths and become Christians, a move which often placed them in conflict with their families, their friends, and the religious authorities. Christianity did not become large enough to have buildings regarded as churches until it became the state religion of the Roman Empire. Until then, the early Christians worshipped in house churches presided over by the owners of the house, who were both women and men.

We hear of these early house churches in Paul’s letter to the Romans, which was written twenty or more years before any of the gospels. In Romans, chapter 16, Paul addresses greetings to the movers and shakers of the early church in Rome, recommending Phoebe, the leader of the church at Cenchreae, and Prisca and Aquila, whose house church had been the church in Rome in the early 50s CE before being expelled, along with the Jews they resembled, from Rome by the Emperor Claudius. Paul lists men and many women and describes them as “working hard for the Lord”; that is, they were leaders in their church community. Interestingly enough, the name of Peter, the later symbol of church power in Rome, is not among them. Other members of the “twelve” are also conspicuously absent from Paul’s list.

Paul’s other letters indicate that many of the early church leaders were women. Aside from Prisca, Paul mentions Mary, Junia (the prominent apostle), Tryphosa, the “beloved” Persis, and Julia. Paul apparently worked closely with these women, and they were important enough for him to mention them by name, some with titles of authority. Leaders in the early church rose organically from the assembly of the people. Their gender didn’t matter since all had been made one in Jesus Christ.

Ordination in the modern sense did not exist, and the only priest Jesus, Paul, and the early converts in Palestine would have known would have been the high priest in Jerusalem. Jesus never used the words priest and ordination, and neither did Paul. Instead, Paul used the word diakonos or deacon. He uses that same word to refer to Phoebe, the female leader of the church at Cenchreae. The Greek word diakonos means servant or waiter and is hardly an honorific term indicating any kind of prestige.

The egalitarian nature of the nascent church unfortunately only lasted until the end of the first century, as Christianity adapted to the cultural mores of the time, which did not encourage or respect the equality of the sexes. As Sister Carol Zinn has noted, religious life makes the shift along with culture and society, even when it takes steps away from the good news of the gospel and fails to produce the fruits of the Spirit. None of the people mentioned above, including both Paul and Peter, could have imagined what the Way of Jesus would become in a couple of centuries.

When Christians did begin to build churches after aligning with the Roman Empire, churches did not immediately become sacred edifices, holy in themselves. In his book The Early Liturgy to the Time of Gregory the Great, Josef Jungmann wrote that early Christian churches were built as an honored place for the assembled community to meet once they grew too large to meet in people’s homes. However, the actual walls, the icons, and even the clergy were secondary to the sense of the community that met to worship God in spirit and in truth. In fact, the earliest name of the church was “house of the assembly.” Only later did the building where the community came to meet become known as church, eventually acquiring other connotations. In the beginning, it was the people of God that held pride of place.

Travelers to Europe have seen the very ancient, very tiny, very primitive churches that are scattered across the countryside. Throughout history, churches located in the small villages and towns throughout Europe were this small with the big cathedrals reserved for major cities like Paris, Cologne, and Rome. Small church communities were the rule in the early days of America as well, until the major cities grew due to the large influx of Catholic immigrants in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This huge growth in the Catholic population necessitated the building of the large urban parishes—the very ones that are now in decline.

Thus, Catholics in America have become accustomed to worshipping in large fancy churches with stained-glass windows, marble columns, statues, and ornate, gold-trimmed ceilings, all of which were paid for by the original members of the parish, who gave what was in many cases their meager dollars to build their parish church. Many people still prefer to worship in these big fancy churches because church doesn’t seem like church without a sizeable building and a clergy attired in expensive ceremonial dress, in spite of Christianity’s humble beginnings.

However, meaningful worship occurs just as well in small churches, in chapels, and in the home, as those who once attended home Masses know so well. Consequently, there is no need for church to be a big, fancy affair with a big overhead. Church is, and always has been, the People of God gathered together in the holy name of Jesus. Consequently, what we call church functions as well in a rented space or in a family living room as it does in a grand cathedral with incense and a bishop’s throne, just as it did in a village church designed for twenty people so many years ago.

Theologian John Dick expresses the worth of small faith communities in his blog, Another Voice:

Yes! We need to put on our thinking caps, because we need to shift from large congregations to intimate small size communities. Large parishes can be divided into smaller neighborhood prayer groups and study groups. Mega churches have the energy of a football game; but small communities have the energy of the human heart. This is not downsizing but reconfiguring.

Just as church buildings have changed over the centuries, so has the church, in spite of protestations to the contrary. Catholics might have forgotten or not know how much church teaching and practice, which did not emerge fully formed from the acts and ideas of the apostles in the first century CE, have changed over the course of the last two millennia.

In the beginning, for example, the Jesus movement was a literal hodgepodge of different Christianities splashed across southeastern Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East. The tenets of these groups—the Nestorians, the Ebionites, the Apollinarians, the Pelagians, the Sabellians, and the Arians, just to name a few—developed at the beginning of Christianity as followers of Jesus tried to figure out how to be Christian. Each worshipped in a different manner, read from their particular sacred books, and developed their own theologies, which contained their own nugget of truth that led them to God.

It took a couple of church councils called by Roman emperors and almost five hundred years to determine that Jesus was consubstantial with the Father and had both a human and divine nature. It took about the same amount of time for the twenty-seven books of the Christian Bible to be canonized into what Christians call the New Testament from among the scores of sacred books that had been written in the course of those four hundred years. What became the prayers and liturgical practices of the Mass were determined by political as well as religious powers. It was not until the eleventh century that the pope had the power to demand the standardization of the liturgy.

This variation in teaching and practice continued in the Middle Ages. In the early days of Christian worship, the people were active participants in the Mass who responded aloud to prayers said by the bishop or the presiding priest. By the eleventh century, the custom changed as the liturgy became the sole province of the ordained priest rather than “the work of the people.” The priest now whispered the liturgical prayers at an altar placed against the back wall of the church, away from the eyes and ears of the assembly. In some churches huge rood screens divided the priest and the Eucharist from the people of God. No longer able to see or hear what was transpiring on the altar, the people began to engage in private devotional practices during Mass that had nothing to do with the liturgy.

It was not until the Council of Trent (1545–1563) that the church systematized liturgical practices, reduced the number of sacraments to seven, defined transubstantiation, and reformed the many abuses that led to the Reformation. It wasn’t until Vatican II that the people regained their voice during the liturgy.

As this little snippet of church history demonstrates, change is always assured. Nature itself teaches us that the only thing that is certain about life is that things will change. Glaciers grow and make their way to the sea and then melt. Great mountain chains form huge peaks and then wear down through erosion. Volcanoes erupt, burying once vibrant towns. Ice ages come and go. Great groups of people migrate from one place to another due to changes in weather patterns, natural disaster, famine, or war. New religions grow and overpower the old. Great civilizations fade away. Nothing is guaranteed forever, and eternity is a long time for things to remain the status quo.

As Stephen Cox suggests in his 2014 book American Christianity, nothing and nobody can really prevent change from happening. The New Testament, with its perennial call to conversion and transformation, serves as a “provocation for change.” Even the most hierarchical denominations are not, Cox writes, immune to change from both within and without and from both the bottom and the top.

It is impossible to find an American religious group that turns the same face to the world today that it did one hundred or even fifty years ago. Instead of staying in one place, American churches have wandered across the landscape, abandoning old sources of support and discovering new ones, in a continual process of self-conversion.

The proliferation of huge Pentecostal and non-denominational churches both in the United States and in once solidly Catholic South America, coupled with the diminishment of once-prominent mainstream Protestant denominations, prove Cox’s point.

In addition, all Christian denominations, including Catholicism, are exposed to what Cox calls “the DNA of the New Testament,” which leads followers of Jesus to discover new meanings in ancient words, actions, and rites.

An example of this is the development and evolution of Catholic sacramental theology. Catholics have been taught that Jesus instituted the seven sacraments during his short life and that these sacraments have remained unchanged for two thousand years. Joseph Martos is one of many theologians who has written that this understanding of the sacraments is simply untrue. In his book Deconstructing Sacramental Theology and Reconstructing Catholic Ritual, Martos asserts that the church arrived at this fairly recent understanding of the sacraments by uncritically interpreting ancient texts from the earliest days of Christianity and then passing mistaken ideas onto succeeding generations of people. Instead, Martos argues, the nature of the sacraments evolved, along with doctrine and practice, as the church was exposed to different cultures and ideas throughout the ages.

In addition, the Roman Catholic Church is, of course, as much a social and political entity as it is a religious one. Knee deep in whatever culture in which it has existed, the church as always adapted to the prevailing social and political environment. The faith of a poor man dedicated to the care of the poor morphed into an imperial cult with a supreme ruler and a court of princes once it moved out of people’s homes and into the emperor’s palace. Consequently, what appears to be a current radical shift of moving towards small Eucharistic communities guided by members of the community rather than by an organized hierarchy might not seem to be so radical at all in light of the many changes that have occurred across two millennia. ♦

How to Keep Your Parish Alive is available directly from Emergence Education Press and other online retailers. Michael Centore is the editor of Today’s American Catholic.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!