Can We Call God “Mother”? Julian of Norwich Says Yes by Shannon K. Evans

It’s no secret that Christians are wary of feminine depictions of God. Despite our righteous insistence that God is neither male nor female, the truth of our belief is quickly outed the moment someone dares use a feminine pronoun to refer to the Divine. While we routinely use “He” for our supposedly genderless God, the moment an “S” is inserted accusations of heresy start rolling in. When it comes to challenging our spiritual imaginations, Christians can be a defensive lot.

Yet at the same time, universal interest in the Divine Feminine is increasing rapidly. In the age of #MeToo, as many of us deconstruct patriarchal ideals and work to decolonize our faith, there rises a collective longing to encounter a God who is more than one-dimensional; a God who is at once male, female, and, well, gender-nonconforming; a God who is expansive enough to contain us all. But are we allowed to imagine such a God?

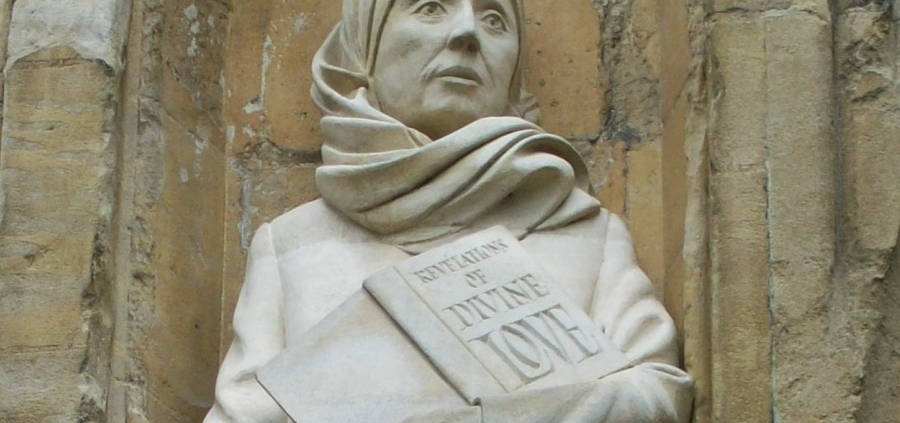

Medieval anchoress Julian of Norwich says yes. “Even as rightly God is our Father, so is God rightly our Mother,” she insists in Revelations of Divine Love, her written record of the 16 mystical raptures she experienced in 15th-century England. The anchoress was profoundly formed by her experience of the fullness of the Trinity, God in three Persons, whom Christian doctrine teaches to be the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Although the gender of the Holy Spirit is not specified, it is by default given masculine pronouns; and so, at the very heart of our beloved orthodoxy is the exclusive maleness of the Godhead.

But an all-male Godhead is not what was revealed to Julian of Norwich in her visions, or “showings,” as she called them. The accounts given in Revelations of Divine Love, the first book written by a woman in the English language, frequently refer to a revelation of God as Mother. Julian’s unapologetic commitment to maternal language and imagery is particularly strong when speaking of the Trinity. Over and over she writes things such as, “For the almighty truth of the Trinity is our Father, for he made us and keeps us in him; and the deep wisdom of the Trinity is our Mother in whom we are all enclosed; and the high goodness of the Trinity is our Lord . . .”

Hers is not a carefully curated theology or biblical exegesis. The life and writings of Julian of Norwich are free of agenda: she neither tries to teach nor persuade, but simply to share the nourishment of the mystical encounters she was given. She does not call God “Mother” to be subversive. She was a devoted anchoress, a daughter of the church; she had no use for creating drama. Julian of Norwich simply experienced in her own soul the ecstatic bliss of union with Ultimate Wholeness itself, and found no other way to express that kind of wholeness than to use both genders to describe it.

Perhaps the key to our own wholeness, individually and as a church, could be the same. After all, who we believe ourselves to be is always a reflection of who we believe God to be. Could a more complete view of God heal places in us that we cannot currently even see as broken? Dame Julian calls us back to our true substance: “Our substance is our Father, God almighty, and our substance is our Mother, God of all wisdom, and our substance is in our Lord the Holy Spirit, God of all goodness.”

There is nothing intrinsically wrong with a male portrayal of God. But there is much that is wrong with making all other portrayals impermissible. After all, an exclusively male God can never mirror back to women our truest selves. Are we not also the imago Dei, image bearers of God? And if there is only a Father in heaven, what about the people, men and women alike, who have been hurt too deeply by men to receive a Father’s love? Does God not long to reveal Her love to them in a way they can best receive it? And perhaps most importantly, an exclusively male God can never embody true wholeness and completion: a balance of masculinity and femininity is necessary for that.

Relating to a Mother God will not be as transformative for some of us as it is for others; we are each unique in what ignites fire in our hearts, which is why there as many metaphors for the Divine as there are people who seek it. Naming God is like trying to hold the wind in your hands: only a loving attempt to catch the uncatchable. Even still, every name gives us one more piece of the puzzle, one more breath of the mystery, one more way we might be healed and freed. Julian of Norwich saw the necessity of naming God “Mother,” and to those who are asking for it, she gives permission to do the same.

Shannon K. Evans is the author of Rewilding Motherhood: Your Path to an Empowered Feminine Spirituality and Embracing Weakness: The Unlikely Secret to Changing the World. She is a regular contributor to Franciscan Media’s magazine, St. Anthony Messenger, and writes the Everyday Ignatian column at Jesuits.org. With her family of seven, she makes her home in central Iowa, where she is actively involved in the local Catholic Worker. Read more of Shannon’s work at her website here.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!