Thomas Merton’s Journey to Dharamsala by Michael Ford

During my university years, I kept on my desk a small portrait of Thomas Merton in a gold frame. He was my guiding spiritual light, and I always sensed he was keeping a close eye on me as I waded through all my theology and philosophy books which formed a “seven-storey mountain” beside us both.

But it wasn’t only a common interest in the monastic life which brought us together: we both loved jazz. In particular, Merton liked its power, unity, and drive which helped him imagine other realities. Within his own four walls, the records of Ornette Coleman and Jackie McLean were as much companions to him as the works of Saint Thomas Aquinas and Saint John of the Cross. The peaceful hermitage in the woods could sometimes sound like Birdland.

In fact, I felt I could almost hear the faint sound of a sax as I approached the pyramid-shaped hills of Kentucky in a corner of the United States noted more for its production of bourbon whiskey than the contemplative musings of a jazz-loving writer. I remember my excitement that hot September afternoon, traveling beside neatly harvested cornfields and towering oaks, when I suddenly caught sight of the white-faced Abbey of Our Lady of Gethsemani coyly emerging through the trees.

Since my student days, I had often imagined what Merton’s enclosed world must have looked like. It was hard to believe I was finally arriving at the monastery where the 26-year-old novice had begun a journey that would radically change his own life—and the lives of many others too. I had once passed the jazz clubs of Greenwich Village that Merton had frequented in his more self-indulgent days.

Now I was 800 miles away from New York, sizing up an enclosure that had somehow managed to contain not only the most influential American Catholic author of the 20th century but also a fearless global campaigner for peace and social justice. On the flight from LaGuardia to Louisville, where Merton had once applauded the city’s jazz musicians, I sensed the monk’s story had all the spiritual passion of A Love Supreme by John Coltrane, who, like Merton, was a constant searcher who believed in common essences.

Jazz percussionist and meditation teacher Richard Sisto was a member of a marginal group of poets, musicians, and artists with whom Merton felt a particular affinity because, like monks, their lives were a contradiction of, and an enigma to, functional, materialistic culture. Merton would even practice Eastern forms of meditation with them. Sisto told me how he had moved to Louisville and played at 118 Washington, a jazz club where Merton would occasionally show up: “The owner turned to me on a break one evening and said, ‘That monk is in here again.’ Soon after I met Merton through a priest friend, I would visit him at Gethsemani, usually on one of the lakes, drinking beer and talking about God and Zen. He was engaging and totally present to you if the conversation and topic were genuine and timely. When the talk was over, he could be abrupt, another quality I admired and shared. I was reading most of his works at the time, and he gave me a few unpublished documents that have since been printed.

“I was raised a Catholic and attended the seminary in Chicago for a couple of years so it was easy to resonate with him, moving from the Christian mystics to the Zen masters and yogis. He made everything we were into at the time become more significant. His encouragement and approval of our direction was amazing. I have had a dream about him that confirms him as one of my true spiritual teachers. I often quote him to my meditation students. His loving openness and great enthusiasm for the spiritual path is something that will remain with me forever.”

One of the most helpful pieces of advice Merton gave Sisto concerned the need to avoid “the larger context,” where the possibility of success might be greater, in favor of a smaller place where he would have more time to think and pray. Richard Sisto followed the guidance and later went to live with his wife, Penny, on a farm adjoining Gethsemani where they raised nine children, including the actor and producer Jeremy Merton Sisto.

Merton always desired to bring together the basic principles of monasticism within different religious traditions; in fact, he saw them as already united. And just as there was a continuity between the Eastern and Western forms of monasticism—an underlying bridge that had not been crossed—so the simplicity of Cistercian architecture was, in a sense, a continuation of the Zen form.

On my tour of Gethsemani, I discovered an enclosed area where the Trappist had once constructed a Zen garden as a place of peaceful meditation for fully professed monks. Every Easter morning, a two-foot-long orange fish kite would be suspended on a pole so its large, wide mouth could catch the wind and float around in the breeze. The graveled garden conveyed a stark beauty and featured an eye-catching piece of limestone that looked like dark, porous moon rock.

Zen, which Merton deemed an important instrument of his apostolate, derives from the Chinese word Ch’an and means meditation. Merton comes close to an understanding of Zen when he describes contemplation as “life itself, fully awake, fully active, fully aware that it is alive” (New Seeds of Contemplation). Zen is a realization rather than a doctrine, a disciplined way of being present, of stilling and silencing the mind from mental distractions and suffering. While never a religion, philosophy, method or system, Zen is an ontological awareness of pure being beyond subject and object. This does not mean, though, that one is closing oneself off from people in the world but, on the contrary, becoming more open and compassionate toward them. No Man is an Island is not only the title of one of Merton’s books but also a fundamental concept in Zen thinking.

After dismissing oriental mysticism in his younger years, Merton came to appreciate the importance of experience over verbal formulations. He was attracted to the writings of Daisetz Suzuki, the noted Buddhist monk and Japanese Zen scholar, regarded as the foremost interpreter of Zen in the West. They exchanged extensive correspondence for several years and, in June 1964, Merton returned to New York City for the first time in 23 years to meet him. Suzuki informed Merton that his book The Ascent to Truth was popular among Zen scholars and monks. This was no doubt because Merton wasn’t interested in purely abstract metaphysical systems but in intuition. Moreover, he discerned something close to Zen within the Christian mystical experience. Merton’s pamphlet The Zen Revival, published by the Buddhist Society of London, was sold and promoted by its members as the most reliable expression of Zen. (In one of his letters, Merton says he feels he understands Zen Buddhists more than Roman Catholics).

It was Merton’s intense study of the Christian mystical tradition, through such figures as Pseudo-Dionysius, Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, Meister Eckhart, and Saint John of the Cross, that both grounded him in the spirituality of his own faith tradition and provided him with the freedom to connect more meaningfully with the wisdom of the East. His detailed knowledge of the Western mystics enabled him to enter into fruitful dialogue with representatives of Eastern religious traditions. Perceiving the unity of all reality, he saw that the goal of all spiritual discipline was a transformation of consciousness. But to achieve it, a person had to be liberated from attachments. He felt that, just as Greek philosophy and Roman law had contributed to the formation of Christian culture, so Western Christian thought would have been “immeasurably enriched and deepened” by an openness to Eastern philosophy.

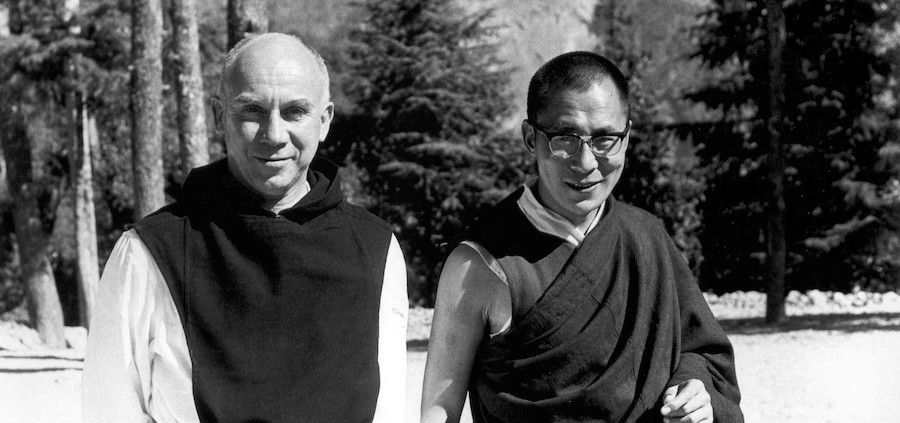

During his Asian pilgrimage, a month before he died in 1968, Merton had three long meetings with the Dalai Lama in Dharamsala, India, where the Tibetan spiritual leader was living in exile. The Dalai Lama remarked that the Cistercian had introduced him to the real meaning of the word Christian. He believed that Buddhist monks and nuns could learn much about the practical implications of compassion through Christianity’s record of charitable work, especially in schools and hospitals. “When you see the photograph of Merton with the Dalai Lama, they look like two cats who’ve licked up all the cream,” one correspondent noted. “The whole relationship between the Tibetan monastic world and Christianity altered on that day—and it has been altering ever since.”

It must be remembered, though, that as a pioneer of interfaith dialogue, Merton was never a syncretist and knew the limits of ecumenism. But what he learned from other religions improved his understanding of Roman Catholicism. In Merton’s eyes, genuine dialogue should not end in communication but in communion—a joining of hearts, but with each person remaining faithful to his or her own religious search. The essential monastic experience is always centered on love, he pointed out. There is only one thing to live for, and that is love. This is surely another reason why Thomas Merton remains a prophetic voice for the interreligious world of today.

Michael Ford is an author and former BBC journalist. He lives in England. His email is hermitagewithin@gmail.com. This article has been adapted from “Unmasking the Self: The Faces of Thomas Merton” in his book Spiritual Masters for All Seasons (Paulist Press, 2009).

The Japanese word “Zen” is not derived “from the Chinese word Ch’an,” nor does it simply meditation. The Chinese word 禪那 was a transcription of the Sanskrit ध्यान or dhyāna, which refers to a state of perfect equanimity and (later) associated with enlightenment itself. To practice dhyana (or to generate dhyana) was likened to meditation in European languages. The word “Chan” (contemporary pinyin spelling) is the Mandarin pronunciation derived from the medieval word; however, Japanese “Zen” is not derived from the modern Mandarin pronunciation. In fact, the medieval pronunciation of the Chinese word (probably *d͡ʑiᴇn in IPA) was most likely much closer to modern Japanese “Zen” than modern Mandarin. So just call it “Zen.”