Eucharist: An Opportunity for Familial Reception? by Ray Temmerman

In the Code of Canon Law of the Roman Catholic Church, Canon 844 §1 specifies the administration of the sacraments to Catholics alone. It then immediately goes on to allow for exceptions. For example, when there is no availability of Eucharist within their own church, Catholics may receive from non-Catholic ministers in whose Churches the sacraments are valid.

Two corollaries should be noted. In order to receive the Eucharist in this situation, it must be appropriate, from the Catholic perspective, to be received by those ministers and their churches. Given that some of those churches are not welcoming of people who are not their members, it must be equally appropriate for Catholics to, in the words of Susan K. Wood, “risk the real pain, the profound embarrassment, the wrenching experience of exclusion” that may result from engagement with such ministers and their churches.

Canon 844 §3 allows for Catholic ministers to administer the sacraments of penance, Eucharist, and anointing of the sick licitly to members of Eastern Churches which do not have full communion with the Catholic Church if they seek such on their own accord and are properly disposed. It appears sufficient that such Christians be properly disposed, and of their own volition seek participation in the sacraments in the Catholic Church.

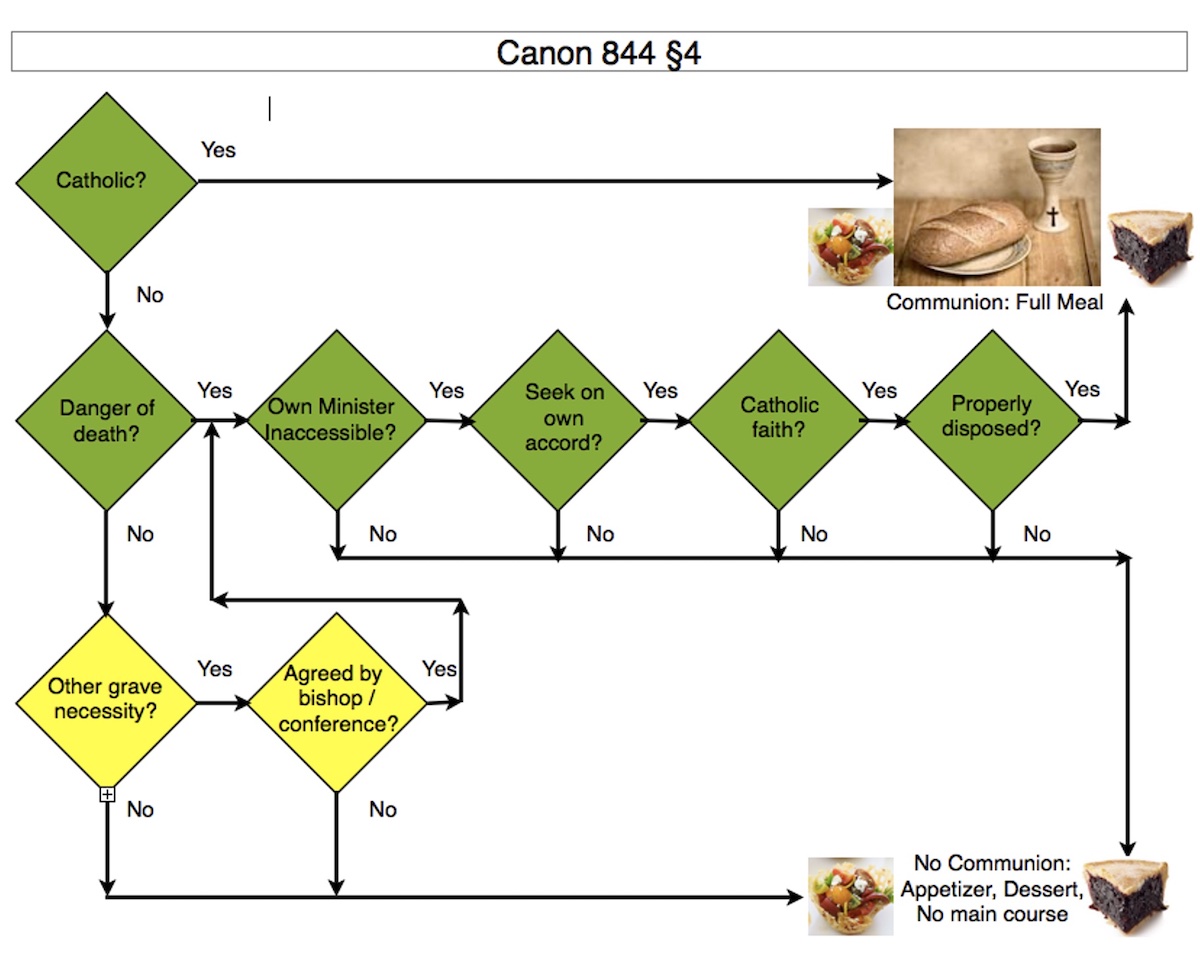

Finally, people of other Christian traditions can be received within the Catholic Church. Canon 844 §4 states: “If the danger of death is present or if, in the judgment of the diocesan bishop or conference of bishops, some other grave necessity urges it, Catholic ministers administer these same sacraments licitly also to other Christians not having full communion with the Catholic Church, who cannot approach a minister of their own community and who seek such on their own accord, provided that they manifest Catholic faith in respect to these sacraments and are properly disposed.“

The conditions are clearly outlined and expanded on in the Directory for the Application of Principles and Norms on Ecumenism (DAPNE). It states that where the Eucharist, penance, and the anointing of the sick are concerned, “in certain circumstances, by way of exception, and under certain conditions, access to these sacraments may be permitted, or even commended, for Christians of other Churches and ecclesial Communities.”

Exceptions are not situations in which the law can be broken, but rather situations in which the law does not apply—something outside of, or beyond, the norm. The norm involved here is that the sacraments are for those in full communion with the worshipping community. The exception, if granted, would be to extend sacramental participation to a person not in full communion.

Some dioceses and episcopal conferences have published their own directories on Eucharistic sharing. Some give lists of events as examples of where an exception may be granted. Where such exceptions have been granted, they have been welcomed and celebrated. But what has been the experience of the faithful regarding the granting of exceptions?

While I am not able to speak for all, I can provide some indication from the perspective of interchurch families, couples bound together as brothers and sisters of Christ through baptism, and made one in marriage. Living in their marriages what Pope John Paul II called “the hopes and difficulties of the path to Christian unity,” they can, as Pope Benedict XVI said, “lead to the formation of a practical laboratory of unity.” They are on the front lines of this issue, impacted Sunday by Sunday, most often (though not exclusively) within the Catholic Church. Their experience indicates several responses:

- Very often, if the event is not listed, no exception is deemed possible.

- It is presumed that a minister of the person’s tradition is always available, even in cases where the couple is worshipping together. It would appear the spouses must make a choice: either 1) they uphold the unity of their marriage, and refrain as one from receiving the sacrament in recognition of the divisions between their churches, or 2) they deny the unity of their marriage to receive individually the sacrament of unity in their respective traditions—and in that denial perhaps render themselves improperly disposed.

- The person of another tradition is presumed not to have a Catholic faith in the Eucharist.

- The issue of disposition is seldom broached.

In baptism, we are raised to the dignity of sons and daughters of God. We become members of Christ, “incorporated in the Church.” All who are baptized are formed into God’s people, provided the minister of baptism intends to do what the church does, and that the baptism is conducted with water and the trinitarian formula.

There is also a history of speaking of our brothers and sisters in Christ—members in Christ’s body, the church, albeit through other Christian traditions—as being “separated brethren.” This term has led many to see these brothers and sisters as somehow “other,” not really “one of us.” It is worth looking at the origins of the term. Orientalium Dignitas (1894) spoke of fratres dissidentes, or “dissident brothers.” Orientalium Ecclesiarum (1964) spoke of fratres seiunctos, a term translated into English as “separated brethren.” That same term is taken up in Unitatis Redintegratio (1964), where once again it is translated as “separated brethren.”

According to G. H. Tavard, one of the drafters of Unitatis Redintegratio, Cardinal Baggio, a noted Latin scholar, requested that the term seijuncti be used instead of separati. Separati, he argued, “would imply that there are and can be no relationships between the two sides; seijuncti, on the contrary, would assert that something has been cut between them, yet that separation is not complete and need not be definitive.” Tavard suggests a more appropriate terminology would be to speak of estranged brothers rather than separated. The nuance does not come through in the English translation, yet the difference is important.

Rather than seeing Christians of other traditions as being somehow separated from the body, needing to be reattached to have life, we can rightly see them as still connected, still part of the same body to which we also belong. Even though the bodily tissue is damaged and in need of healing, the body is still one. There is still a flow of nutrients and neurological signals between the parts. Unity still exists, is still real, though in a manner which is less than perfect. That lack of perfection, however, lies not at the level of being truly brothers and sisters, but at the level of estrangement between true brothers and sisters.

What would happen if we began referring to Christians of other traditions as “brothers and sisters from whom we are estranged”? Would we begin to recognize them as still part of the same body of which we are also part, still connected, even though the body may be damaged, the connections tenuous and in need of repair? Would we see that estrangement requires two to be involved, i.e., that we have as important a role to play in lessening the estrangement between us as does the person from whom we are estranged? To slightly modify a phrase by Susan K. Wood, even though all people are born into the human community . . . our incorporation into that community takes place only within a particular concrete household.

We humans normally eat and drink in our own household, where we are familiar with the family’s recipes and rituals. In more affluent societies, it is now more common to go out to eat, but the norm is still to eat in one’s own home. To eat in another’s home, even that of a brother or sister, is exceptional. And to do so in the home of a sibling from whom one is estranged is exceptional indeed. This, I suggest, is an appropriate context for the term exception.

To go into the home of a family member from whom one is estranged, to eat and drink with that member, where access to one’s own recipes and rituals is unavailable, is an activity full of risk, rightly called an exception. Will one be well received? Or rejected, turned away? One is not familiar with the rituals, the behaviors considered appropriate. One believes only that there is real food and drink here, and that eating and drinking together can help to heal the estrangement, to restore the family unity. Such eating and drinking may take place around a baptism, a wedding, a funeral: events which hold commonality and so reduce the risk.

I would argue that the events themselves are not the exception. Rather, they reveal the primary exception: the act of going outside one’s own home to the home of a family member from whom one is estranged, with all the risk that entails, to eat and drink together with the intent of building family unity. This involves two receptions: the estranged sibling receiving the Eucharist, and the church receiving the estranged sibling. The presence of an estranged sibling in the community’s central act of worship constitutes a call to that community to receive that estranged sibling.

How will the church community respond? With a presumption that the sibling rejects the community’s guidelines for table etiquette? Or with a presumption that, even if the specifics of that etiquette are unknown by the sibling (as can often be the case), the sibling is still seeking to reduce the estrangement, to heal the body? Will the body of Christ be recognized as present only in the sacred elements, or also in the person of the estranged sibling (cf. 1 Cor. 11:29)? The selected presumption, conscious or subconscious, will largely dictate the community’s response.

If we simply take the words of the canon and obey them, I suggest we will find it very difficult to receive anyone from outside our church without extreme vetting. If, on the other hand, we take those same words and apply them within the context of an exceptional act, I suggest we will find ourselves far more able to receive the gift of God present in the form of the estranged sibling. Is not the very desire to reduce estrangement between brothers and sisters (Christ’s call that “all be one”) sufficient to warrant sharing the Eucharist with Christians not fully in communion with us, provided all the remaining criteria are met?

Unfortunately, people of other traditions seldom get far enough to have their case tested against the criteria. Instead, as can be seen in the graphic below, the decision is made well before they get to the criteria.

Let us not forget that “the res et sacramentum of Baptism is membership in that body, that Church,” and that “the res et sacramentum of the Eucharist is not just the risen body of the Lord, but the whole Christ, the Church.” This must surely include those brothers and sisters who have come to our home, as siblings from whom we are estranged, to eat and drink with us and so rebuild unity.

I return to the question in the title of this essay: can we find it in ourselves to receive an estranged member of the family who risks joining us for a meal? Can we presume that this is one like us, a pilgrim on the way to the unity for which Christ prayed? In such a situation, can the Eucharist, rather than a sign of delineation and separation, be viaticum, food for the journey for all who receive? If so, then the Eucharist can indeed become an opportunity for familial reception. ♦

Ray Temmerman (Catholic) and his wife Fenella (Anglican) are actively involved in the Interchurch Families International Network (IFIN), and worshipping together as much as possible in both their churches. Ray also administers the IFIN website, available here.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!