Dream of Faith by Roger Karny

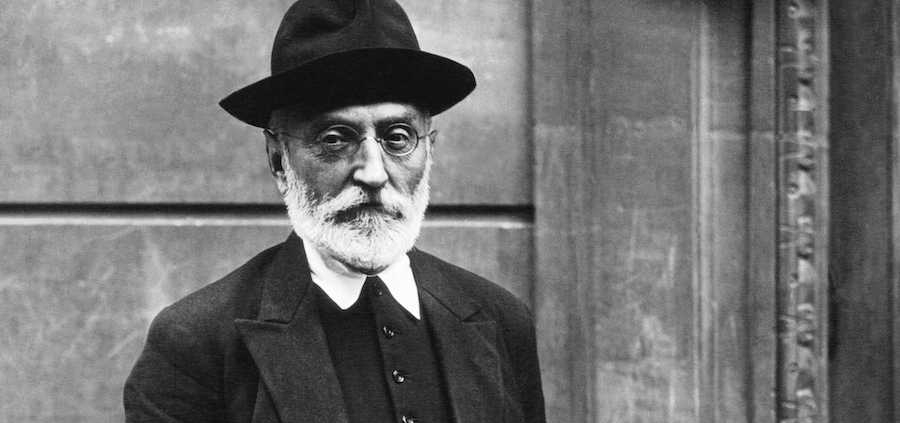

Muiguel de Unamuno y Jugo was a Spanish linguist, philosopher, essayist, novelist, poet, and rector of the Universidad de Salamanca, one of the oldest universities in the world. With an independent, reflective mind, he conducted a lifelong search for what he honestly believed. He wouldn’t be pigeonholed in his thinking, nor would he stand for someone else forcing their rigid, stale dogma on him. In this way he was similar to French philosopher Simone Weil, who also could not bow to prescribed Catholic tenets nor reject her friends who were freethinkers or atheists.

Unamuno believed in God and an afterlife. But he could not bring himself to believe with his thinking mind. He felt that humans needed to believe their lives had some transcendent meaning, something that carried on after their deaths. Only with this belief could one live and work effectively. In his essay “¡Adentro!” (“Inside!”), he proposed that one should first look inside oneself; one could then find the source of strength and goodness needed to reach out compassionately and help others.

Unamuno knew 14 languages, including Danish, in which he read Søren Kierkegaard in the original. He agreed with Kierkegaard that faith clashed with reason, but he still urged faith on his readers in a Don Quixote–like quest against all reason. Like many Spanish writers of the “Generation of ’98,” he admired the persistence of Cervantes’s Quixote, seeking a rebirth of Spain’s values and legacy through an understanding of the knight’s memorable quest.

In his nivola (a literary genre he invented to distinguish from the realistic Spanish novelas of the time) San Manuel Bueno, Martir (Saint Manuel Bueno, Martyr), Unamuno presents his personal struggle with belief in a short story about a Spanish priest, Don Manuel Bueno. Dom Manuel serves his parish lovingly and faithfully but is unable to bring himself to have faith in an afterlife. He is neither an atheist nor an agnostic. He simply cannot believe, even though as a faithful prelate he spends his days teaching those of his beloved pueblo to do so. And though almost no one understands why, whenever he prays the Apostles’ Creed aloud with his parishioners, his voice falls away at the words “I believe in the resurrection of the dead and life everlasting.”

Don Manuel seems to believe in Jesus and God, but mostly in a humanistic, worldly way. It’s not clear that he thinks that Jesus is eternal. God himself seems to be distant and quite unconcerned with the trials of human beings. Dom Manuel suffers like the martyred Christ, but for a different reason. He knows his mission is to serve the church and the people around him, and to convince them to believe in the afterlife—which they do, in a kind of dreamlike way. They believe like children and have no inkling of the cross their priest staggers under. In fact, Dom Manuel is so unsettled by his doubts that he feels a continual temptation to suicide by drowning in a nearby lake. His only salvation is to flee solitude through constant good actions toward his people.

Only the narrator of the story, Angela Carballino, and her brother Lazarus are privy to his secret. Ironically, Dom Manuel “raises” Lazarus from his “dead” faith in modernism and progressivism to “faith”—but this is the same faith that Dom Manuel has, a faith that the people of the pueblo need to believe and be ministered to, even at the expense of their own spiritual freedom. This is the only way Manuel knows he can “convert” Lazarus, to reveal to him the secret of his own doubt.

After many years of selfless service to the pueblo, Dom Manuel dies. Later Lazarus also perishes, leaving Angela alone. The people and the church want make Dom Manuel a saint because of all the good he has done. Angela, who as a young woman was fervent in her traditional Catholic faith, allows the canonization process to proceed, although she knows of Dom Manuel’s disbelief. She believes the “dream” of the people must continue in order to help them navigate their lives. Angela ends the story with these soul-searching words: “Y yo? Creo yo?” (“And I? Do I believe?”). One can see the dual nature of Unamuno’s own conflict here. Angela represents the emotional side of belief, while Don Manuel and Lazarus the more rational, skeptical aspect. Who among us does not have some measure of this dichotomy?

Unamuno experienced his own crises of faith. While he and his wife had nine children, one son died at age six, greatly affecting the philosopher’s belief. He was also relieved of his position at the University of Salamanca and exiled for six years from his native Spain by the dictator Primo de Rivera. He was placed under house arrest by General Francisco Franco in 1936, and tragically died shortly thereafter.

In an English translation of the introduction to Unamuno’s magnum opus, Del Sentimiento Tragico de la Vida (On the Tragic Sense of Life), one finds this apt description of the Spanish thinker: “A true heir of those great Spanish saints and mystics whose lifework was devoted to the exploration of the kingdoms of faith, he is more human than they in that he has lost hold of the firm ground where they had stuck their anchor.”

Unamuno’s writings were condemned by the Spanish Catholic Church, which was extremely reactionary and linked with the traditional Spanish monarchy, the conservative landed aristocracy, and the military. It did not look well on progressive ideas or nontraditional theology that lacked its imprimatur, its stamp of orthodoxy.

There needs to be a place for both the Catholic Church and the Unamunos of our world. It does no good to try to silence one in order to promote the other. Perhaps not everyone can hold both perspectives in fruitful tension. But all the truth must come out: the truth of God at play as well as the truth of our doubting, searching humanity. Unamuno was courageous for confronting the realities of his life and thought—and likely the realities of others as well—in the regressive climate of early 20th-century Catholic Spain. ♦

Roger Karny is a freelance writer living in Colorado, and a graduate of Swarthmore College. He worked for 30 years for social services. His articles have appeared in the Industrial Worker.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!