Summer Reading Series: Patrick Henry on the Work of Eva Fleischner

The Memory of Goodness:

Eva Fleischner and Her Contributions

to Holocaust Studies

Edited and Introduced by Carol Rittner

and John K. Roth

Seton Hill University Press, 2022

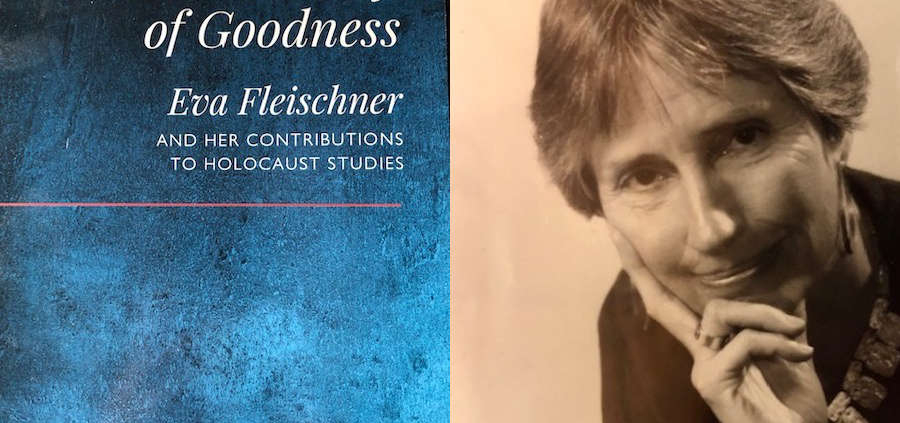

Born in Vienna in 1925 to a Catholic mother and a Jewish father, Eva Fleischner fled the Nazis to England in 1938, where she was educated in a convent school administered by French nuns in Brighton. She eventually settled in the United States in 1943. Eva attended Radcliffe College in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and studied medieval philosophy at the University of Paris. She finished a PhD in Religious Studies at Marquette University in 1971, writing a dissertation entitled Judaism in German Christian Theology Since 1945: Christianity and Israel Considered in Terms of Mission. She then began a 20-year teaching career at Montclair State University and a brilliant scholarly career specializing in the Holocaust and Christian-Jewish relations.

In The Memory of Goodness: Eva Fleischner and Her Contributions to Holocaust Studies (Seton Hill University Press, 2022), editors Carol Rittner and John K. Roth, two internationally known Christian scholars of the Holocaust, collect 12 essays written by Fleischner and arrange them equally under three rubrics: Teaching, Rescue and Responsibility, and Jewish-Christian Relations. The book also contains a chronological account of Fleischner’s life, a list of her publications, a short chapter by the editors on “The Significance of Her Identity,” and four hugely important documents related to Christian-Jewish Relations: Nostra Aetate (1965), a declaration on the relation of the Catholic Church to non-Christian religions; “The Vatican and the Holocaust” (2000), a preliminary report issued by the International Catholic-Jewish Historical Commission; Dabru Emet (2000), a Jewish statement on Christians and Christianity issued by the National Jewish Scholars Project; and “A Sacred Obligation” (2002), a rethinking of Christian Faith in relation to Judaism and the Jewish people issued by the Christian Scholars Group on Christian-Jewish relations.

Passion and Compassion

All of Fleischner’s work is marked by passion and compassion—perhaps, above all, her teaching. In the spring of 1973, as a faculty member in the Religion Department of what was then Montclair State College (it would be redesignated a university in 1994), she was one of the first teachers of the Holocaust in the United States. Her classes focused on the moral and religious issues raised by the Shoah. Her goal was to rescue students from ignorance, blindness, and apathy toward the past and awaken them to the injustices in the world they were living in. Among other things, she repudiated the traditional Christian teaching of anti-Judaism, insisted on the fact that Jews did resist the Germans and did not go to the slaughter like sheep, taught the rescuers of Jews during the Holocaust, and broke down the “we/they” dichotomy between Christians and Jews as she forged new common paths for both to follow together.

Fleischner’s sensitivity and compassion struck me particularly when she tells of the “grey zone” inhabited by Jewish children who were hidden during the Holocaust, sometimes for several years, often baptized and taught Christianity, and whose parents were murdered by the Germans. “Who” were their real parents? Those who gave them birth and then “abandoned” them, or those who saved their lives and whom they often came to love? “What” were they, Jewish or Christian? The younger the children, the greater chance that they didn’t already have a Jewish identity before the war. The younger the children, the greater the confusion.

Fleischner navigates this “grey zone” with understanding, gentleness, warmth, and perspicacity. “There are thousands of men and women in Warsaw today,” she writes, “who are not sure who they are. Some are devout Catholics who have discovered that they were born to Jewish parents and have decided to remain Catholic. Some have been able to embrace their newfound Jewishness with enthusiasm. Others are afraid to acknowledge their Jewishness publicly because there is still antisemitism in Poland. They are afraid to ‘come out’ as Jews.”

Christian Responsibility for the Holocaust

In her writings, Fleischner, who remained a devout Catholic until her death, lays out clearly the anti-Judaism and antisemitism inherent in early Christianity and the two thousand years of the “teaching of contempt for the Jews” in the liturgy, preaching, catechesis, and theology of Christian churches throughout the world. Even though “Christianity is born out of Judaism and is wholly Jewish to begin with,” she depicts the absurd charge of deicide against the Jews in full bloom already in the fourth century, the Constantinian era, and cites Saint Augustine as one of its defenders. “They bear guilt,” writes Augustine, “for the death of the Savior, for through their fathers, they have killed the Christ.”

Not only does Christianity bear deep responsibility for the Holocaust, in Fleischner’s view, but Christians betrayed the Jews once again during the Holocaust. She admonishes Christian churches for having “failed shamefully to speak out on behalf of the Jews.” She also underscores the silence of Pope Pius XII, who “never publicly condemned or excommunicated Hitler.”

The Need to Teach the Rescuers of Jews During the Holocaust

Year after year, in her teaching, Fleischner “deliberately omitted rescuers from [her] Holocaust syllabi out of fear that focusing on rescuers would somehow detract from the experience of Holocaust victims.” But Harold Schulweis, the founder of the Jewish Foundation for the Righteous, convinced her that, in addition to the victims, the perpetrators, and the bystanders, we must teach the rescuers because they are part of the historical record and because our world needs “heroes, models of courage and decency” who give us reason to hope for humanity.

Fleischner went on to interview more than 50 rescuers and to teach their stories and motives for their altruism. She was particularly gratified to teach Catholic rescuers, because whereas the church failed completely as an institution, she could point to many of its most devout members who acted like true Christians during the Shoah. Ordinary people did some extraordinarily evil things during the Holocaust. But a small number of ordinary people did some extraordinarily good things at that same time: they risked their lives, and in many cases those of their children, to shelter and save strangers from the clutches of the Germans. Fleischner hoped that by teaching about the “few,” she could help create a world where they would have become the “many.”

Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel

The editors of The Memory of Goodness note that “No mentor was more important to Eva than Abraham Joshua Heschel.” This is also true of the present writer, who grew up in New York City and witnessed the great civil rights leader who marched next to Martin Luther King Jr. in Selma, the great peace activist who cofounded CALCAV (Clergy and Laity Concerned About Vietnam) in 1965, perhaps the central interfaith force alive in the 1960s. Heschel considered Pope John XXIII “a great miracle,” and his impact in Christian circles was so great that he was often referred to as a “shailliat la-goyim,” an apostle to the Gentiles.

Heschel spoke in brilliant, original aphorisms: “God is greater than religion.” “Faith is deeper than dogma.” “Religion is a means, not an end. It becomes idolatry when seen as an end in itself.” “No religion is an island. We are all involved with one another.” “Religious pluralism is the will of God.” He moved his audience deeply at Notre Dame University in March 1966 when he said: “A Jew, in his own way, should acknowledge the role of Christianity in God’s plan for the redemption of all men . . . I recognize in Christianity the presence of holiness. I see it. I sense it. I feel it. You are not an embarrassment to us, and we shouldn’t be an embarrassment to you.” In 1972, two months before he died, Heschel spoke in Rome at an interfaith conference that included Muslims. “The God of Israel is also the God of Syria and the God of Egypt,” he claimed. “God is either the father of all men or of no man.”

In her writings, Fleischner elucidates the central role Heschel played not only in the United States but in Rome during Vatican II, where he worked steadily to improve Judeo-Christian relations. Fleishner was not the only one to believe that “Rabbi Heschel may have done more to inspire an enhanced appreciation of Judaism among non-Jews than any other Jew in post-biblical times.”

A Sacred Obligation

Certainly, awareness of the Holocaust heightens our sense of responsibility towards its victims. This sense of responsibility is what inspired Fleischner and the other members of the Christian Scholars Group on Christian-Jewish Relations to issue their “Sacred Obligation” document in 2002. I will end by citing the 10 points made in the document, all of which are deliberately opposed to the distorted way Jews were characterized and denigrated in Christian churches before the Holocaust. “We urge all Christians,” the authors write, “to reflect on their faith in light of these statements. For us, this is a sacred obligation.” The 10 points are as follows:

- God’s covenant with the Jewish people endures forever.

- Jesus of Nazareth lived and died as a faithful Jew.

- Ancient rivalries must not define Christian-Jewish relations today.

- Judaism is a living faith, enriched by many centuries of development.

- The Bible both connects and separates Jews and Christians.

- Affirming God’s eternal covenant with the Jewish people has consequences for Christian understandings of salvation.

- Christians should not target Jews for conversion.

- Christian worship that teaches contempt for Judaism dishonors God.

- We affirm the importance of the land of Israel for the life of the Jewish people.

- Christians should work with Jews for the healing of the world. ♦

Patrick Henry is Cushing Eells Emeritus Professor of Philosophy and Literature at Whitman College in Walla Walla, WA. He is the author of We Only Know Men: The Rescue of Jews in France during the Holocaust (2007) and the editor of Jewish Resistance Against the Nazis (2014).

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!