TAC Synodality Week: A Long and Winding Road by Nicole d’Entremont

I believe the Roman Catholic faith is no greater nor lesser than any of the other great faith traditions in the United States or in the world. With that said, I still consider myself a Catholic, even though the church I attend is not Catholic and welcomes all who wish to participate regardless of their religious or nonreligious orientation. What draws me to this church is its daily commitment to community, social justice, the arts, music, kids, and stewardship of the earth. It’s not just a “Sunday thing to do,” and if I decide not to go on a Sunday, that’s really my own business and not an affront to God.

So, why do I care about Pope Francis’s effort to resuscitate a church that certainly is in even greater decline than it was back in 1961 when John XXIII convened the Second Vatican Council? I do because, against all odds, I still care about the church in which I was raised. I once told a priest I know in Canada that I don’t feel I left the church but that the church left me. He responded with good-natured laughter. He is from a country in Africa and is ministering to the colonies of North America. The tables have turned.

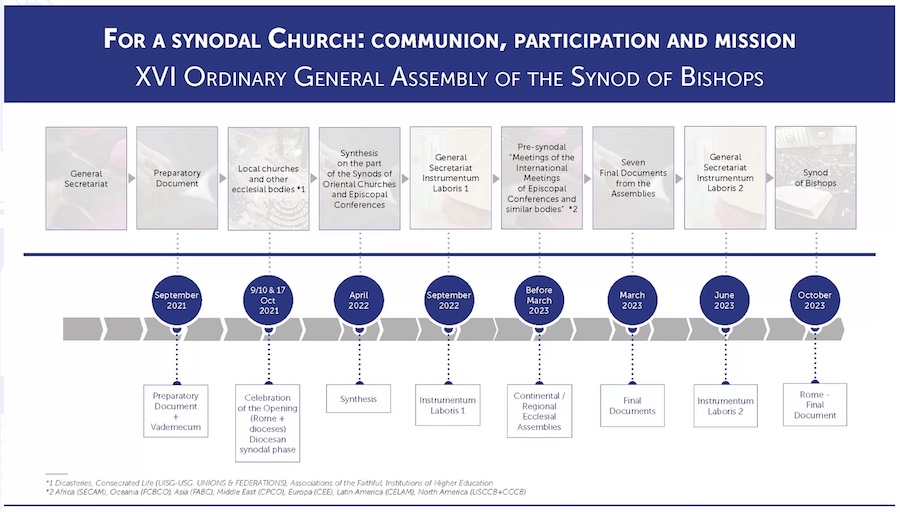

Now in the 21st century, Pope Francis has called on clergy and laity around the world to gather in groups to listen to one another about the challenges facing the church today and, afterward, to submit a report that will be compiled for a synod (an assembly of bishops—and, yes, I had to look the word up) to be held in Rome next year. The Sixth Ordinary Assembly of Bishops will gather in October 2023 to discuss these findings and ultimately render a concluding document. No parishioners will be at the table at that point, nor diocesan priests or sisters still left walking the beat in religious life. I doubt that a Catholic youth delegation will be present to participate in the ultimate discussion and summation. A recent survey of Catholic youth reveals that they do participate in faith activities but not through their involvement in any particular parish life.

I suppose I was one of those youths in 1961. I took religion seriously, but parish life revolved mostly around going to Mass and confession, receiving the sacraments, and feast day observances. Catholic school and catechism lessons were handled by the convent nuns. I can remember the Catholic Worker newspaper arriving from New York City every month in the mail to our home, and certainly the message of that paper, both in the art and the articles, was a fusion of the Catholic religion and social action, but I don’t remember those subjects being addressed seriously in sermons from the pulpit.

By the time I was 19, things got interesting with a young Catholic president being elected and a new pope calling for throwing wide the windows of the church to engage the modern world. I was a freshman at a Franciscan college and still a believer, even though my course in dogmatic theology felt like an iron lariat thrown around my head. That summer, I attended a National Student Association Conference in Madison, Wisconsin. There I met student editors of college papers and also students, both white and black, who had just come back from the American South after being jailed and beaten for attempting to register black voters in Mississippi. I wanted to get involved and write about all of that for my college paper, which I did, and I also started going down to New York City, to the Bowery, where the Catholic Worker had its soup kitchen. It was there that I saw the multiplication of loaves and fishes in real time and the Gospel became more than words in a book. By 1962, I was going down to the Catholic Worker regularly and finding there what was missing for me in the church.

By 1963, our bright hope of a Catholic president had been assassinated and I was protesting the war in Vietnam. I remember once during that time going to Mass with my parents and the priest saying that bayonets should be used on protestors. I should have walked out. By the fall of 1964, I had left college and joined the Catholic Worker Movement where the Sermon on the Mount was being lived in action and more fully expressed than what was emanating from the Vatican or local parishes.

It is my belief that during those years the church lost a generation of active, socially engaged Catholic youth through its temerity and its lack of moral courage and guidance during a crucial period in our national history. We live a similar world of internal turmoil today, both nationally and within the church, only with one large generational difference: few of the children born of my 1960s Catholic generation—and, subsequently, their children today—profess any strong affiliation to any parish life. The Catholic Church as a cohesive neighborhood force has all but disappeared, a relic of big edifices and empty pews. There was liturgical reform, for sure, but other potential reforms languished. Discussion about married priests and women being ordained were off the table. Homosexuality and the issue of birth control other than the “rhythm method” was not up for debate. Forty years later these same issues remain unresolved. Now, add to the Vatican II leftover list are new areas of concern such as clerical sexual abuse, gender fluidity, who should and should not receive communion, same-sex marriage, and climate justice.

In my own life, the sustenance I received from the institutional church during that whole period of civil rights and peace activism came basically from the actions of purported outliers: activists such as the Fathers Phil and Dan Berrigan, writers such as the evolutionary theologian Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, and other nameless, ordinary people, seekers, workers, and volunteers who passed through the door of the Catholic Worker.

Now we have an effort by Pope Francis to try again to engage a spirit of renewal by throwing wide the doors of the church. The process through which this will hopefully be achieved is through the actions of a synodal church, a church that stresses working together as a community through respectful, communal listening sessions, participation, and mission. The jury, of course, is out in terms of how many worldwide Catholics are responding to this call and how the Vatican is reacting to the responses so far, although there is already controversy regarding the German bishops being chastened by Vatican authorities for revealing their more liberal reaction to the first listening phase.

I wanted to see how the synodal path was intended to unfold here in the United States, so I went to the website of the United States Council of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) for the instruction manual outlining procedures. Simply put, here is what I discovered.

First, there are diocesan listening sessions involving parishes, diocesan priests, and lay groups. These sessions are organized around questions about the church as people have experienced it in their lives. After these discussions conclude, a synopsis of the sessions is sent to the USCCB. (Lay groups also have the option of submitting their reports directly to the General Secretariat.) The USCCB gathers these submissions together and synthesizes them, thus creating another group synopsis that is then sent on to the General Secretariat of the Synod of Bishops in Rome. Since this is a global effort, this process is repeated in episcopal conferences throughout the world.

The General Secretariat of the Synod creates its own summary based on syntheses from the episcopal conferences as well as other reports received. This becomes the initial Instrumentum Laboris, or “working document,” for pre-synodal gatherings of the seven continental meetings: Africa (SECAM); Oceania (FCBCO); Asia (FABC); Middle East (CPCO); Latin America (CELAM); Europe (CCEE); and North America (USCCB and CCCB). These seven international meetings will, in turn, produce seven final documents that will serve as the basis for a second Instrumentum Laboris, which will be presented and debated by the full 16th Ordinary General Assembly of the Synod of Bishops in Rome in October 2023. The text that comes out of these discussions will be presented for Pope Francis’s review. Hopefully, the results of the final vote will be released immediately and the advisements to Pope Francis revealed to the public.

Throughout my research, I had a persistent and gnawing concern as I read how synopsis after synopsis after synopsis was being generated as the basis to frame the generalized content of the concluding document to be voted upon by the assembly. A synopsis is a general view. Such a view requires a serious reduction in specific content. What happens, then, when synopsis after synopsis after synopsis becomes the building block for the final voted-upon document?

Granted, this attempt at a worldwide conversation is daunting, but because of that, I believe, it is crucial that key examples from the initial stories of the first listening sessions illustrating why and for what reasons participants feel the way they do about the Roman Catholic Church should be included in that final document. The bishops assembled should not be shielded from these stories. Stories, not generalities, have power. They give context and reality to our reflections. Christ revealed his message to us through parable and story. Why should we do less?

My own story will end with this reflection. My mother’s parents were Presbyterian missionaries in China for 33 years. My grandfather was a surgeon and my grandmother taught Bible study, nutrition, and health. In her Bible study classes, the one question my grandmother was asked that she had the hardest time answering and was embarrassed to even need to explain was why do Christians, who all believe in the same Jesus Christ, have so many different churches? We all live under the same sky; no one is higher, and no one is lower, at least from that vantage point.

Perhaps the Holy Spirit invoked in much of the literature I have recently read will infuse the deliberative body in Rome with the spirit of inclusion. If not, the message sent will be that this particular door to Christianity will remain shut to the very people who have worked so hard to keep it open. ♦

Nicole d’Entremont is the author of two novels and a third, currently making its way around the sun, seeking publication.

I read, with growing interest, Nicole’s story/history. In it, I saw a reflection of my own journey—though mine was through the ‘soup kitchen’ of absorbed rigidity. I moved, very slowly, from that conservatism to an understanding of religion as relationship. Now, there are meetings to talk about synodality, yet my experience of those events do not include attentive listening. Now are they experiences of awareness. Instead, it seemed that that majority of the attendees were much more interested in solidifying the status quo or, better yet, empowering the return of a pre-Vatican II church. I see it in the parish…committees, groups, and—sadly, liturgies. It’s a mad dash backwards. I remain, even though I am a thorn in the side of those who will not or cannot hear my pain, my passion, my desire for the universality of the church. So, in a sense, I am also attending a church which is not Catholic. However, it is also not welcoming “all who wish to participate regardless of their religious or nonreligious orientation.” It does not offer opportunities to a “daily commitment to community, social justice, the arts, music, kids, and stewardship of the earth.” Bravo to Nicole for seeing a vision beyond sight and for offering it to all of us. Shalom, Fran

I have long since stopped thinking that the Church can change. Its fundamental allegiance to the concept of paternalistic god and consequent world order, results in its leadership consistently aligning with the wealthy an powerful. Perhaps no hierarchical institution can do otherwise, but it’s certainly clear that none of the major Christian denominations have shown any desire to surrender their hypocritical embrace of power and wealth and follow the path of Jesus, loving the poor, the sick and the outcast, unconditionally. The ‘churches’ of Jesus, Buddha and Muhammed, are not found in buildings or institutions dedicated to their founders, but in the hearts and actions of individuals who attempt to live their teachings of tolerance, selflessness and inclusion.

.

I agree with both Fran and Dan in their accessment of both the current and historical institution of the Roman Catholic Church. My allegiance is with those still within the Church who are working for change. On occasion, I still go again to a Catholic Mass. I still like going into an empty Church (although now most of them are locked up during the day) and visiting the Blessed Sacrament. Maybe I am the prodigal daughter. But, I feel welcomed by a presence beyond the fierce God I was introduced to while studying the Baltimore Catechism in 1948. That kind of Church, those doctrinaire and judgmental attitudes, cannot banish me. I think this current tectonic shifting under the Rock of Peter is necessary and overdue. I await a new structure.