Seeing the Church through the Webb Telescope by Gene Ciarlo

Astronomy, astrophysics, and cosmology sound esoteric and distant because they are, in the sense that they deal with the study of the universe, its origin and evolution. Add to this a cosmology dealing with beliefs based on mythological and religious traditions focused on realities beyond this earth. In religious circles, this is better known as eschatology. It is a rare instance indeed when we hear anything of these sciences on the nightly news, but that is what has happened recently as we have gained new insights into where and who we are in this mysterious universe.

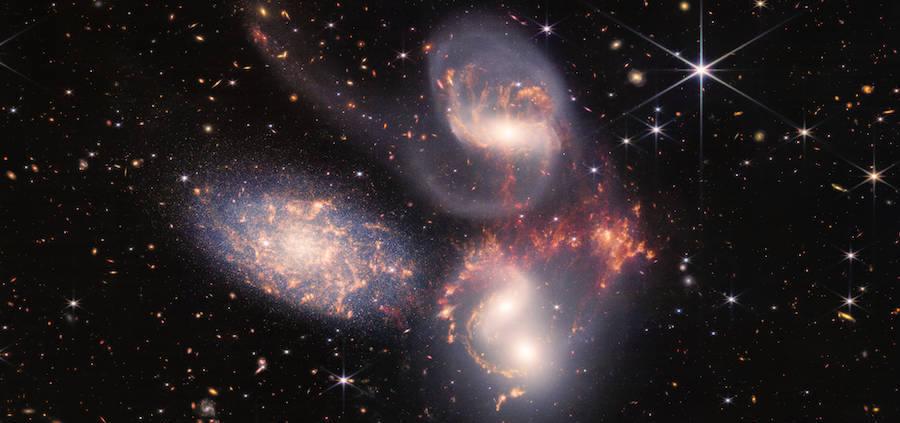

I am speaking, of course, of how the world’s interest has been summoned to the field of astrophysics via images from the James Webb Space Telescope. It projects us back to the beginning of time—if time ever had a beginning—to the origins of the universe, the billions of galaxies and the infinite reality of space ever expanding. The mystery captivates us yet boggles our minds, because the concepts of infinity and timelessness are beyond our comprehension.

That kind of awakening to a greater reality compels us to stop and think about our earth, our planet, our logic, our reasoning and understanding of who we are and what we are all about. There is an unearthly, undoubtedly spiritual dimension to it. It is almost unimaginable that we are alone, that earth-life is alone in this vast, apparently endless universe. It also forces us to wonder about more personal terrestrial realities: how small we are, how petty our squabbles and battles, our wars that kill thousands and millions of people all for the sake of power and authority, ownership and superiority.

Add to these new revelations the notion of God, religion, and spiritual life, concepts that have been with us since creation began reflecting upon itself (to borrow Teilhard de Chardin’s definition of a human being), more commonly known as the advent of human existence. Religion is as old as we are and equally as mysterious.

I think it is safe to say, in the 21st century, in view of our expanded knowledge, that there is no single religion capable of holding a monopoly on truth—one that is complete and perfected, whole and infallible on timeless and ageless matters and nontangible spiritual realities. We were guided to believe that Christianity—or even more specifically, Catholicism—was the one true religion, revealed by God, complete and unchangeable because it dealt with divinely revealed, eternal truths.

In theological terms, we Catholics called that body of truth divine positive law because it was beyond our control or manipulation, established by God and therefore immutable and timeless. As a result of this conviction about God being always with us and not allowing us to fall into serious error, the churches, Christianity in general and Roman Catholicism in particular, made some very serious blunders over the centuries in the name of preserving, protecting, and advancing God’s truth.

Yet perhaps we fault religion too much for what has transpired on this planet in the centuries since Jesus walked the earth and tried to teach us about God. Christianity made great strides during the 19th century, regardless of the many political-historical missteps during World War II that cast a deep, dark shadow over the Catholic Church and the Vatican. Remarkably, in the mid-20th century, religions all over the world (and in the Western world in particular) were growing stronger, more vibrant, more powerful and influential in both the secular and religious arenas of life. Like the giant sequoia, religion seemed invincible, indestructible, having been tested by fire. That was Christianity, and arguably Catholicism was leading the pack in its number of adherents and popularity throughout the West. It seemed like a postwar spiritual renewal. Rome, the Vatican, and the papacy stood tall. We were a proud people.

Meanwhile, imperceptibly, our intellect, our understanding, our knowledge of all things natural and even supranatural (though not necessarily religious) were growing slowly but surely, bringing us a new knowledge of ourselves, of our world, and of the universe around us. Examples such as the Webb Telescope and the advent of artificial intelligence only stand to confirm the significant material aspects of this human growth and development.

Responding to the Signs of the Times

Truth be told, the former belief in the invincibility of religious belief and practice—and I speak here mostly in terms of Roman Catholicism—is dying, and the death is surreptitiously painless, or so it seems. Unawares, this is painful to the cause of truth, justice, compassion, other-centeredness, and the community of humankind. Along with Christianity, once powerful in numbers but now in serious decline (especially in the Global North), humanity is beginning to suffer, apparently oblivious to what is actually happening. We are hurting because the principles that were the backbone, structure, and base of Christianity, creative of our human society, are crumbling fast, meaning that our care for one another, the community of humankind, is threatened and suffering.

Let me be more specific. In the geopolitical world, we put a lot of stock in the European Union, NATO, and “Western alliances.” All imply strength through unification. Christianity was the moral equivalent of that international strength; it gave culture and morality a wall against selfishness, greed, power, and individuality. Christianity was a buttress and bulwark against human weakness and selfish, self-destructive pride.

What has happened to us? The worldview and progress of human society has changed dramatically, but the worldview of the church has hardly kept up with what is happening around us. We are lost in a long-gone era of spirituality and religiosity that is no longer effective or valid.

In post-biblical times, in matters of God and the spiritual life, it was assumed that all we needed to know had been revealed. According to Saint Thomas Aquinas, all public revelation ended with the death of Saint John the Apostle. We can now appreciate that time and human evolution have changed that way of thinking. Every aspect of life is in flux, gradually and almost imperceptibly changing, until we find ourselves at an omega point, a point at which we realize what is happening: that we can no longer hold those truths as complete, God-given, and immutable. The Webb Telescope can be for us simply a launchpad, a symbol and a summons that forces reality, even spiritual reality, upon us to help us come to a new awareness of ourselves, our universe, our environment, and what we call our God. Common sense, technology, human development, the passage of time with concomitant intellectual and spiritual growth, have all come to the fore to help us to see. What is this new vision?

In our Roman Catholic Church, there is a crying need for us to be brought into the 21st century. The Synod on Synodality is a silent confession that something radical must be done, as we are dying on the vine. We have to face existential realities and be responsive to the needs of today’s world or we will further stagnate and disintegrate into practical nothingness, becoming totally ineffective and irrelevant save for a handful of “the devout” who are compelled to accept a resigned feeling of helplessness and inadequacy relative to the order of the world.

A New Worldview: A Revitalized Spirituality

The way we Christians present ourselves to the world depends on what we believe. In turn, what we hold sacred is manifested in our worship, how we come together to acknowledge who we are relative to God and the world. The first order of business, therefore, is what we believe. Our prayer and communal worship will demonstrate that. In turn, the world will know who we are by what we think, say, and do. So what do we believe about God, Jesus, and our place in this cosmic wonder that we call earth?

The Catechism of the Catholic Church, published in 1994, received a second English edition in 2016 for the explicit purpose of presenting a revised translation of the various texts of Mass and sacraments. Each topical paragraph in the catechism is numbered for the sake of reference, allowing for easy access to particular topics. This comprehensive encyclopedic endeavor is intended to cover the entire gamut of beliefs, doctrines, teachings, and official prayers of the church. The use of scripture, including the Hebrew Scriptures as well as the Christian Testament, is comprehensive, with extensive footnotes and references on each page.

The sections that interested me as exemplary texts were about creation and Jesus. I wanted to see what the theologians who produced the catechism had to say about the universe, the world, and creation as it is related in the Book of Genesis. The results are amazing—and appalling. They do not take into consideration any discoveries of cosmology, the scientific study of the universe, but rather convey a primitive notion of how the universe began and how sin and evil entered the world. It is as if natural disasters and death and destruction originated with the sin of Adam, regardless of the fact that planet earth was bombarded with evil in a multitude of ways millennia before the advent of humanity.

As for Jesus, he is not looked upon as a human being, a person like us, who offered and manifested a new way of living through the pitfalls and shortcomings of life on earth for each and every person down through the ages. Instead, it appears that any and all biblical citations that might apply to a messiah were seized upon and then applied to the man Jesus of Nazareth, almost forcing him to conform to “predictions” and “prophecies.” The result is a caricature of a savior, an impossible human being who is more outlandishly inhuman rather than a person, a man, a divine being filled with the spirit of God who was born of a woman into a profoundly human environment. Is this the Jesus that we are supposed to relate to and understand as the merciful, compassionate, loving God whom we want to emulate and turn to in our joys and sorrows, and with whom we are to find answers in an increasingly more complex and “me-first” world?

How can it be expected that educated, mature people living in the 21st century and beyond will build their spiritual lives, their deeper, more profound lives relating to God and the God-Man Jesus, on an archaic and out-of-touch anthropology, cosmology, and theology lost to another time that is no longer part of our daily existence on planet earth? And people who care about the church and are in positions of authority wring their hands wondering why people living in the modern world have given up on the institution. It is a shame—but a shame on whom?

In spite of all of this, I can still say that Jesus and Christianity are worth it, worth fighting for, because the true story is incredibly beautiful and deserving of a lifetime of dedication and commitment. As impossible as it may seem, and impossible as it may be, Christianity must change radically if it is to survive as a world power—a compassionate and loving power, the power of powerlessness—in an increasingly cruel and self-destroying world. ♦

Gene Ciarlo is a priest no longer active in the ministry. Ordained from the American College, University of Louvain, Belgium, he spent most of his ministry in parish life. After receiving a master’s degree in liturgical studies from Notre Dame University he returned to his alma mater in Louvain as director of liturgy and homiletics. Gene lives in Vermont, where everything is gracefully green when it is not solemnly white.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!