A Long and Winding Road: Part II—An Ecumenical Listening Session by Nicole d’Entremont

Several weeks ago, TAC contributor Nicole d’Entremont contacted me about her plan to initiate a synodal-style listening session at New Brackett Church on Peaks Island in Maine. New Brackett is jointly affiliated with the United Church of Christ (UCC) and the Unitarian Universalist Association (UUA), and numbers among its congregation several former Catholics.

I was immediately intrigued by Nicole’s idea. A key principle of the Synod is learning to listen to those who have been shut out of the Catholic Church’s discernment and decision-making processes. This includes lapsed and former Catholics whose experiences can enrich the church’s self-understanding and sharpen its self-critique.

Earlier this month, Nicole assembled a group of 13 participants, both Catholic and non-Catholic, at New Brackett for an extended listening session. What I find most exciting about the insights gathered here is that they show the Synod evolving in conversation with other denominations; they “weave together relationships” and “create a bright resourcefulness” that Pope Francis has identified as the purposes of synodality.

As the Continental Phase of the Synod begins, it is our hope that the culture of synodality continues to develop both within and outside of the church, and that church leaders and laity alike are inspired to practice a deep and fearless listening. Special thanks to Nicole for facilitating this event and report, and to the participants at New Brackett for sharing their experiences—Ed.

On October 27, the long-awaited Document for the Continental Stage (DSC) of the Synod was revealed to the public. The DSC is the product of thousands of individual synodal synthesis documents produced during the Synod’s Diocesan Phase. These original Diocesan Phase submissions were the result of a worldwide, 10-month grassroots synodal listening period that brought together parish priests, deacons, laity, religious orders, volunteer Catholic and service organizations, and others.

In the case of the United States, the Diocesan Phase involved 700,000 participants and 22,000 reports. Each report was sent to a local bishop, who then sent a synthesis of the aggregate reports to the US Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB). The USCCB compiled their own synthesis of the submissions received. In September, they and other bishops’ conferences around the world sent their syntheses to an international group of experts who had assembled in Frascati, outside of Rome.

The objective of this 10-day gathering of experts was to examine and further synthesize the 112 synthesis documents from the various bishops’ conferences. Twenty-five people were appointed to the drafting committee for what would become the final working Document for the Continental Stage. Each person on the team was responsible for reading a dozen reports. Prior to writing the draft, participants met in small groups to identify themes, notice tensions, and make suggestions. The documents were also read by several theologians.

Out of this collaborative effort, the drafting committee drew up a final synthesis translated into two languages: Italian and English. This final text will serve as the basis for discussions at the seven Continental Assemblies, which are scheduled to be held between January and March 2023.

♦ ♦ ♦

I probably never would have entered a portal leading into this synodal process had I not joined an ecumenical Christian church on the Maine island where I live. New Brackett Church was at one time part of a Methodist denomination and now is, well, itself, and also a member of the United Church of Christ and the Unitarian Universalist Association.

I left the Catholic Church in college and then stubbornly became a Catholic Worker. I joined the Worker’s New York City house in 1964 and participated in and around the movement for 10 years. I had no intention of joining any church after I moved back to Maine and onto Peaks Island years later, but I got involved in a children’s art project sponsored by New Brackett. I started going to Sunday services, and I found that the young minister was smart, and the readings and homilies left me thinking, and the music and choir often moved me to tears—but for good reasons. Plus, since we are on an island, I knew the neighbors I saw at church. I suspected I was not the only former Catholic who had taken refuge in that simple, wooden dwelling.

I started wondering how many former Catholics were part of New Brackett. So, during a Sunday service I brought up the subject. I said I was thinking of writing an article about the current effort to bring the Roman Catholic Church into the 21st century and asked if any former Catholics would be interested in discussing this with me. This resulting second installment of “A Long and Winding Road” (part I is available here) is the response to that question.

On a brilliant October weekend, 13 of us met outside and discussed our relationship with the Roman Catholic Church. We ended up as a mixed group, word having spread about this effort. Included in our assembly were practicing Catholics as well as one person studying to become a Catholic. There was the pastor of New Brackett Church and a retired Catholic priest. The rest of us were no longer practicing Catholics, although I stubbornly refuse to relinquish my identity as a Catholic Worker. We sat in a circle on that beautiful October afternoon and told our stories.

And the operative word here is stories. In my research on the processes of the synodal church, I have read texts built around the various syntheses that have been published locally and bulletins from the Vatican media office. Far too often I found these texts laden with generalities regarding both problems and desires for the state of the church. When language is constrained by generalities and by synopses, you have a problem. A synopsis gives you the outline of a subject; a story gives you the beating heart. My hope is that the deliberative bodies in Rome can still hear that beating heart when the final document is written.

What follows is a transcription, lightly edited for length and clarity, of our synodal gathering at New Brackett Church.

Q: What was your historical background with the Catholic Church?

Nicole: Raised Catholic, 16 years of Catholic education. I was devout as a young girl, went to a Franciscan college in Buffalo, New York, left the church in [my] sophomore year. The church was silent on way too many social issues. I was especially moved after going to a conference in Madison, Wisconsin, and met civil rights workers both black and white who had been beaten while struggling for the vote in the American South. [My] parents subscribed to the Catholic Worker. I went to my first demonstration in NYC against the war in Vietnam in 1961 or 1962. I left college in 1964 and joined the NYC Catholic Worker. I stayed in and around the Catholic Worker for 10 years but [I was] not involved with the institutional church that appeared to have little to say about civil rights or the war in Vietnam.

Andrea: Raised Presbyterian in Michigan. [My] grandparents were Methodists on one side and atheists on the other. In college I fell away from the church through boredom but came back during a personal crisis. I had some problems with the local [Unitarian] church but the music was amazing. The people were kind to my brother, who is autistic. He was treated better in the church than anywhere else. Social workers were paid, but the church was my brother’s friend.

As a young girl, though, I was always drawn to the Catholic Church. The white dresses, rosary beads, saint’s medals. The Presbyterian Church was so boring. All bricks. No candles, ikons, rosaries. I love the Mass. Now I am studying to become a Catholic.

Jan: A lot like Nicole—16 years of Catholic education, grandparents were very religious [with] Polish Catholic [and] Russian roots. I left church my sophomore year. I remember being in Mass and this macho priest was up there, and I have to sit in a pew with a veil on my head. I said to myself, I’m a woman. I’m taking a break. Still on break.

Mernie: My mother was Catholic. We all went to Catholic school. It was scary. Confession was terrifying—can’t eat before communion. I never felt comfortable. I did like the music. We brought our kids up Catholic, but I don’t think we gave them a good picture of the church. When they left home, they left the church. When my husband died, I realized I didn’t have to go. Mass was the same time as Meet the Press. I wasn’t getting much out of the homilies. Every once in a while there was a good one.

John: Cradle Catholic, 22 years of Catholic education, ordained a priest. I think they finally did it to get rid of me. [My] uncle was a priest. My parents had different experiences with the Catholic Church, but they lived their values. I had too much rote memorization in Catholicism until I [met] Benedictine monks in college. They asked what the students thought. I ended up getting good grades in theology. But it really was the army and law school that drove me back into theology. Still, I got accused of being a “pinko.” The Catholic Worker paper radicalized me and keeps me [involved].

Patty: Well, I had 12 years of Catholic education. My parents were from Ireland—six priests in the family. I miss the visibility of Catholic priests in the community. My kids didn’t want to be confirmed. I have devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary. Sometimes I’ll watch Mass online rather than in person. I just don’t feel visible to the diocese.

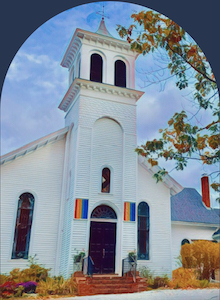

New Brackett Church, Peaks Island, Maine

Jean: Twelve years in. My grandmother was my example. My dad converted because of my mother. He went the whole way. Knights of Columbus—those hot pink capes. We did it all, statues, ikons. I still have my rosary, still pray it in French and English. I left the Catholic Church in college. Later I joined the Methodist Church. Then I went on a retreat and felt the Holy Spirit. The Catholic Church feels so conservative now.

Linda: I went to CCD [Confraternity of Catholic Doctrine, the Catholic catechesis program]. My family is Italian. My mother and grandmother were very devout. My father was suspicious of it. I did the rituals but didn’t get much out of it. I went to the Newman Center in college. But it felt like it was time to go after I heard the priest speak. It was all his way. I left. I didn’t go back to see a priest until my children were born and my family was pressuring me to have them baptized.

I went to a priest. What would happen to my babies? Being sent to limbo and all of that . . . What was that about? He was kind and said, “Linda, I cannot believe God would treat your baby that way.” I was so grateful to him. Years later, I saw an announcement about a female preacher at a [Unitarian Universalist] church. I went. Finally, I could hear about God from a woman.

Will: I’m a former Methodist clergyperson who is now at home in the Congregationalist tradition. In my 20 years of parish ministry in New England, many of my parishioners have a strong relationship with Catholicism. It’s a regional thing! My grandfather marched with the pope when he visited Boston in ’79—an important moment in his life. And he was Knight of the Year in 1984. (I have the citation from Governor [Michael] Dukakis!) I’m a gay, Protestant pastor who is the grandson of a Knight of Columbus.

Connie: Grade school through nursing school—all Catholic. I didn’t leave. I stayed a practicing Catholic during the scandals. When I retired, I wrote my spiritual autobiography. I was in a group of non-Catholic women who were open to hearing why I stayed practicing Catholicism during that time. I explained that my participation was not dependent on the clergy and the hierarchy. The church was my own personal habit, and I wasn’t going to change because of the failings of the church.

Helen: My family was strict: Mass on Sunday, only Catholic schools. Don’t read the Bible on your own—you might misinterpret it. I did get involved in college in volunteer work and then in parish life with my own family, but my big turn was when my first husband got sick and the priest never came to visit. After my husband died, I met a Congregational minister. We wanted to get married but he had been divorced. I went to see my godfather who was a priest, and he said he couldn’t come to my marriage in a Catholic Church unless my intended husband got an annulment.

I have my own relationship with God now. I raised my kids as Catholics but it didn’t stick. Although my children are not following the strict practices of Catholicism, if it means attending Mass every Sunday, they are practicing Christianity in their daily lives and raising their children with the values of Christianity.

Joanne: I’m French Canadian, so Catholicism is baked into the culture. Crucifixes hung in rooms. Infant of Prague dressed up. Rosary during Lent. I didn’t go to Catholic school but had CCD every week. Every Sunday Mass. I was devout and into it. Memorized all the right answers.

Then I got sent to a Catholic high school by the local monsignor who paid for me to go, but I didn’t like it. All those uniforms and sitting in rows—also, some of the rules didn’t make sense, like not saying the ending of the Lord’s Prayer like the Protestants did. Why couldn’t we pray with them with the words they used? I lasted two weeks in that school. But I did go to a Catholic college. I was the first one in my family to go to college. It was the 60s and everything was happening. I got married. I did baptize my daughter, but the hierarchy of the church was impossible. I just quit.

Buck: Dad was Catholic and mom Episcopalian. We went to Mass with my father. My mother didn’t go. I went to public schools through the eighth grade, but then at the behest of my dad’s parents, I was sent to Archbishop Stepinac High School, a Roman Catholic boys school in White Plains, New York. I had to take one train and three busses to get to school from my home in North Tarrytown. It was a great education, but I was not happy. I missed my friends who attended the local high school. When I graduated, the diocese would not give me a recommendation to the college of my choice because I was applying to a non-Catholic school. It was the 1960s and I’d had it. I felt pushed away by the Catholic Church.

Q: If you once were observant, is there anything you miss about the church?

Jan: Wearing a uniform. The ritual around the Mass. The mysticism of the church appeals to me.

Connie: I miss the children when church was a way of life.

Nicole: I miss being able to find an unlocked church door today so I could go inside and kneel in the quiet before the Blessed Sacrament in the tabernacle along with the one lit candle keeping vigil.

Patty: I miss pastoral care.

Jean: The Eucharist. Having it all the time, not once a whatever.

Joanne: I miss the Virgin Mary. The saints. I try and incorporate the feeling of the Catholic sacred into my own rituals at New Brackett Church. I feel different when I kneel after communion.

John: A good piece of bread and wine.

Buck: I don’t feel I am in the house of God in a Protestant church. But I do feel that in a Catholic cathedral like Notre Dame.

Helen: The sacraments, Easter, incense, candles, the sense of mystery as connection.

Q: What have you found in New Brackett Church that you felt was missing in the Catholic Church?

All: Community. Women accepted as leaders in the church as well as the community. People being part of the Sunday service and not just observers. Social justice issues are a priority. Good sermons and good music.

Q: What change is necessary if the Catholic Church is to be relevant in the 21st century?

Jan: Not tolerating but appreciating all religions. [I] wish the church would come clean.

Nicole: Divestiture of wealth. Rectories becoming houses of hospitality for the poor. Gender equality. Women clergy. No bias regarding sexual orientation in the church or for ordination. Married and single clergy. A hard look at the dogmatic theology that pushes people away from the church.

Helen: Recognition of the universality of religion, a gathering together. Ecumenism.

Buck: Concern for the environment. Don’t avoid issues like the death penalty and war and peace.

John: Don’t let religion get in the way of your faith. If the rules aren’t working, scrap them. Prioritize serving others. ♦

Nicole d’Entremont is the author of two novels. A third, Sketching with Renoir, is currently seeking publication.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!