A Father’s Love and Longing by Michael E. DeSanctis

In his award-wining collection of personal reflections on the American way with death, The Undertaking (1997), funeral director and poet Thomas Lynch suggests that grieving is “romance in reverse.” To grieve, according to Lynch, who’s observed the process closely for decades, is gradually to trade the intimacy one ordinarily wishes to share with another for the separation death imposes on their relationship. The living and the dead have new stations to assume in the complex geography of human love and memory, after all, and getting there requires some movement on both their parts.

If Lynch’s observations are correct, then we fathers of a certain age must number among the most practiced of “reverse romancers.” Even should death not be involved, we’re expected to suffer the near-disappearance from our lives of the children who once crawled at our feet but have since migrated to places and circumstances far beyond our reach. The sense of loss this elicits from deep within a father’s psyche is as real and prolonged as any, psychologists tell us. You’d never know it, though, given the lengths most dads will go to rationalize away the pain that results from bidding farewell to their children of a certain age. “It’s just one of those things,” they explain with a shrug, as if it were okay with them, but always with a tinge of regret or resignation in their voices to indicate that it’s not.

The sadness of parting with one’s children is something I’ve had to come to terms with myself as each of my own kids, now well into adulthood, has moved beyond routine contact with me by any means other than electronic. Their flights from the all-too-quiet home my wife and I now inhabit by ourselves was bound to happen, given the seemingly contradictory way in which I conveyed paternal love to them through the respective phases of my life—first by letting them leave my arms, then by letting them leave my household, finally by letting them leave the spheres of my influence altogether to make their own way in the world. Such is the propulsive, forward-directed nature of a father’s affection for his children, seen early on in his willingness literally to push them beyond the wobbliness of their first attempts at bike-riding and routinely thereafter in his pushing them to succeed in school, in the friendships they develop, in their marriages and careers.

What all this “kid propelling” will cost them down the road, however, is something dads are slow to recognize. The truth, as I’ve learned from talking with a good many fathers, is that they are far less eager to part with their children, regardless of age, than the culture generally assumes. Escorting them from one’s house at the appropriate moment is one thing; jettisoning them from one’s heart is quite another. What a father’s love sometimes appears to lack in depth, it more than makes up for in longevity.

An elderly gentleman I know from church, for example, prays at Mass each morning for his drug-addicted son as fervently as he probably did when the lad was just a boy—through he’s now in his 60s. Another dad with whom I’m acquainted who’s facing similar issues with his adult son sums up his dilemma by quoting an old, Italian adage: “Quando i figli sono piccolo, camminano sulle loro mani. Quando crescono, camminano sul tuo cuore.” (“When children are young, they walk on their hands. Whey they grow up, they walk on your heart.”) Even other fathers with whom I’ve spoken admit to fretting daily over the health and happiness of children they describe as “grown and gone” in the matter-of-fact way that the relatives of deceased persons speak of their loved ones as “passed on.”

Often, it’s only after a father’s own death that his secret desire for closer connection with his children is fully revealed, as I discovered nearly a decade ago with the passing of my own dad. Sorting through files in his home office on the day of his funeral, I came upon a manila folder bearing my name in large letters and filled with every journal article, professional citation, or news clipping to have accompanied my career in academia, many bearing notes my dad had scribbled in their margins as if for posterity. It seems the folder had served as a kind of reliquary. In it were stored the tangible traces of how far I’d travelled in the course of an adulthood lived apart from my father, a companion to the baby book stored elsewhere in my parents’ home between whose pages were pressed relics of my childhood.

Perhaps I’m simply too nostalgic for the more frequent contact I enjoyed with my children when they were much younger and did most of their roaming around within the confines of the home my wife and I provided them. Even today, I long for the years when they still called me “Daddy” or intuitively took my hand when crossing a street or entering a strange playground. This was before they dropped the “y” from my title entirely and began making it clear they were no longer in need of the reassurance that a body larger than theirs could provide. Nowadays, there’s both a spatial and a temporal dimension to the distance from them I silently endure. Space separates me on a daily basis from who they’ve become, time from who they once were as cuddly balls of infancy, all need and impulse.

There’s a third factor that contributes more and more to our separation, which amounts to how little recognition they share of our family’s immigrant past. It dumfounds them, for example, to hear me rhapsodize over the importance that something as simple as Sunday dinners once held in the Italian-American households of my youth, nearly sacramental affairs whose arrival each Sabbath afternoon was signaled hours in advance by the scent of tomato sauce, sausage, meatballs, and braciola slow-cooking on my mother’s or grandmothers’ stoves. The aroma of the latter was, to the domestic liturgies of my family, what the fragrance of incense was to celebrations of the Mass in our parish church, proof that something important was afoot in which the senses were invited to take part. The meal itself consisted almost always of macaroni (never called “pasta” by anyone in our circle), a salad course, assorted meats, and a finishing flourish of dolci, fruit, and nuts, all intended to transport partakers of my grandparents’ generation back to the country of their origin. To me, my siblings, and our vast collection of cousins, for whom the form and flavors of such meals were as familiar as our grandparents’ heavy accents, they were reminders that some part of ourselves, too, had originated in a foreign place; though, as so-called “second-generation” Italian-Americans, the Mediterranean blood running through our veins was thought to be significantly diluted. The overcrowded parlors, pantries, kitchens, and front porches that birthdays and major holidays brought to the modest flats in which the various segments of my family seemed to dwell, all peopled by aunts and uncles speaking loudly to each other and with great gesticulation, likewise affirmed our inclusion in a culture that put community above privacy. There were few private spaces one could retreat to in the long and narrow layouts of those homes, anyway, which so closely mirrored each other as to suggest the various segments of our family really did live together.

From what I can tell, “third-generation” ethnicity comparable to anything I knew in my youth a half century ago is virtually nonexistent in this country, so strong is the force of cultural assimilation that makes “Americans” of all of us. Simply too much time has elapsed since great waves of European immigrants arrived in the United States in the early decades of the 20th century for their legacy to affect the latest generation of their descendants in any substantive way. I see this in my own children, whose sense of what their Italian ancestors went through in leaving the “old country” comes only by way of yellowed photographs and verbal accounts of the story that grow less reliable with the passing of each year. They no more regard themselves “Italian” with the same seriousness I did at their age than they do “Italian-Catholic”—which is another matter entirely and further reason for my feeling somewhat divided from them. Even the father who encourages his children to “follow their own paths” secretly hopes they’ll find one that at least parallels his own. When they don’t, however, he’s bound to feel somewhat disappointed, even rejected, and wonder what real impact he ever made in their lives.

None of what I offer here is intended to suggest that mothers don’t likewise fret over the well-being of the children they once carried within the security of their own bodies before releasing them to the less predictable forces of a wider world. Neither am I suggesting that moms don’t suffer the unspoken loss that comes with being a modern “empty-nester,” something that fiction writer Helen Schulman, in a New York Times opinion piece, described as engendering “a mixture of denial and endless hope.” “Believe me,” Schulman writes, “I know in real life we can’t protect our kids forever and, in a profound way, we never really did.”

Maybe children, too, suffer a skewed view of their upbringing and credit their moms more than they should for who’ve they become in adulthood. My hunch, however, is that they naturally gravitate toward the parental figure in whose presence they likely spent the most time as infants and to whom they still look for doses of sympathy and encouragement. Unless mothers fail horribly in their role as “nurturers,” it’s hard to believe that their children wouldn’t will always display greater outward affection for them than for their fathers. A LendingTree survey of 2,000 consumers in 2021, in fact, reveals that Americans spend far more on Mother’s Day activities each year than they do on Father’s Day. In addition, the survey indicated, though dads serve as important financial and practical role models in a household, moms remain their children’s go-tos for affection, emotional support, and financial and practical advice. It seems that the majority of dads wanted little fuss made over them on their special day but preferred to use it spending “quality time with their famil[ies].” Fathers yearn less, apparently, for material expressions of their children’s love, such as cards and gifts, than for time well spent with them.

A built-in aversion to “making a fuss” over much that pertains to their children may turn out to be one of greatest gifts fathers offer them. Research by psychologist Kyle D. Pruett, for instance, has shown that a father’s measured response to the distresses of his sons and daughters in early childhood contributes greatly down the road to their sense of independence and self-sufficiency. Adolescent children, too, apparently benefit from their fathers’ reluctancy to address every problem facing them in their progression toward adulthood. A 2006 study on successful child-rearing released by the US Department of Health and Human Services, in fact, suggests that teens greatly benefit from all that comes with the increased freedoms and responsibilities dads instinctively extend them as an entrée into the adult world. If it’s not exactly “tough love” that fathers appear demonstrate to their offspring, it’s at least a less demonstrative version of the affection reserved for mothers. It may well be that a father’s apparent stoicism is really an act of self-preservation that steels him against the day when he must bid them farewell. The reassuring embrace of others awaits them, after all, and variations on love that a father simply cannot provide.

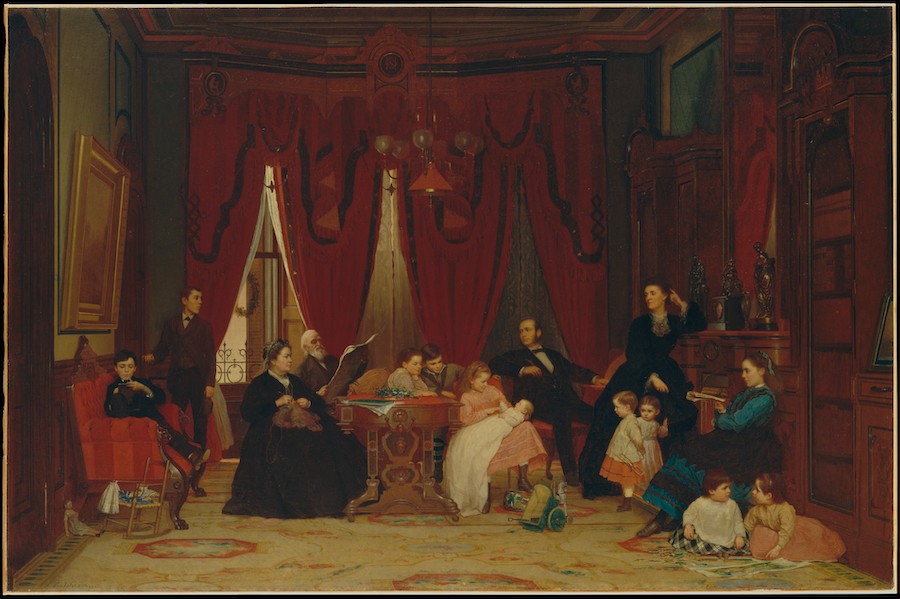

“The Hatch Family,” Eastman Johnson, 1870-71

Even those fathers highlighted in the Bible seem to exhibit a certain dispassion toward the affairs of their offspring that, in reality, may serve to protect them against the pain of having someday to part with them. We can only guess at what it took the patriarch Abraham, for example, to contemplate making a burnt offering of his very son, Isaac, in response to God’s nearly unfathomable command (Gen 22:1–19). Abraham’s obedience to his heavenly father is demonstrated earlier in Genesis, when God tells him to leave behind all that is familiar and familial to him and venture to an entirely foreign dwelling place. “Go from your country, your people and your father’s household,” God tells him (Gen 12:1), and so he does, no questions asked, in order to establish a nobler place for his progeny.

So it was, as well, with Joseph, the so-called “foster father” of Jesus, who dutifully responded to some celestial instructions of his own. Our sense of the man is skewed, unfortunately, by the insistence on the part of Christian artists of all genres historically to treat him as a background figure in Jesus’s life story, significantly older than Mary, his spouse, and virtually bereft of emotions. Our insights into the inner life of Joseph are further compromised by scripture’s failure to record a single word he may have spoken in the course of his service as head of the Holy Family. In fact, it’s only by way of Mary’s reproach of the 12-year-old Jesus cited in the Lucan account of the teen’s solo foray into the shadows of the Jerusalem temple (Luke 2:41–52) that we learn of the prolonged worry the episode provoked in Joseph. We learn that he’d spent three days “grieving” (the Greek word used is θρηνώντας; Luke 2:48) the disappearance of a son on whom he could make no biological claim. Nevertheless, he refrains from reprimanding the boy himself in any way worthy of the gospel writer’s attention, but is described as not comprehending Jesus’s behavior, perhaps as fathers from time immemorial have puzzled over the actions of their teenage children.

Even greater patience, once assumes, is demonstrated by the father described in the parable of the Prodigal Son (Luke 15:11–32), whose son, presuming to have reached full adulthood, asks to be freed of paternal supervision not to venture into the safe and sacred confines of a nearby house of prayer but to taste the thrills available to him in a “distant country” entirely (Luke 15:13). There, various translations of the parable emphasize, the boy indulged in “wasteful,” “riotous,” or “lecherous” activities of the sort that presumably would never have prevailed under his father’s roof. Whether the son realized it or not, however, he’d been the beneficiary of a tremendous gift: license to behave as he chose, as disastrous as this turned out to be. Had his father not granted him the freedom to taste genuine hunger, disillusionment, and regret, after all, the boy may never have had the interior conversion that prompts him, later in the parable, to return home. For his part, the father remains steadfast in his love for his son and may even have maintained something of a lookout for his return, details highlighted by the fact that “even while [the boy] was still a long way off” he runs out to meet him, embraces him, and kisses him (Luke 15:20). The father had lengthened the tether connecting himself to his son, not served it, and entrusted the unbreakable blood covenant between them to love’s mysterious elasticity.

We can assume that whatever waking had been done in the father’s house as a result of his son’s initial departure—his “death” as the Bible puts it (Luke 15:32)—paled greatly in comparison with the celebration that ensued upon his return or “rebirth,” when, ringed and robed like a bridegroom, he and other guests were treated to music, dancing, and the choicest foods. Not surprisingly, the “older brother” described in Luke’s account of the parable is perturbed by this, not fully appreciating, perhaps, the long-suffering nature of parental love. Are we to conclude, like him, that the father is a pushover? A poor rule-keeper? A weak, “spare-the-rod” type who’s bound to have his heart broken again if he’s not careful?

I think not, recognizing that scripture uses all three of the father figures cited here to reveal something about the divine fatherhood it ascribes to God himself. God is the generative power that wills all persons into existence, to be sure, but no less an infinite source of mercy and forgiveness that are by their very nature regenerative. Indeed, Catholics are reminded from time to time by the collect of the Mass that God “restores all that he creates and keeps safe what he restores.” He behaves as an attentive farmer would, unwilling to allow any of his crops to fail on their own without doing everything in his power to cultivate them toward a state of health and abundance.

This certainly rings true with my own attempts at fathering, which, for better or worse, consist of equal parts loving and longing. It’s to the neediest of my children that I invariably devote my greatest efforts, not the most self-sufficient. Perhaps I glimpse in them some part of myself, false-fronting it on most days to appear beyond needing them to be regular presences in the life I currently lead but secretly harboring a desire to have them as close by as when they were “my babies.” An invisible umbilicus, albeit emotional, binds me to them that’s every bit as real as the one that connected them long ago to their mother’s life-giving body. I’m not about to sever this connection, which is as much supernatural, as I see it, as natural. Nor will I allow my nostalgia for an earlier chapter in our lives prevent them from travelling as far from my side as their dreams carry them. I entrust them, instead, to the care of the God who goes on fathering all of us his own way, the perennial parent who loves us into being and longs to count us forever among the members of his household. ♦

Michael E. DeSanctis, Ph.D. is retired professor of fine arts and theology at Gannon University in Erie, Pennsylvania. He writes widely on Catholic church architecture and serves as a liturgical designer and consultant.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!