The Irish Broadcaster with a Deep Catholic Faith by Michael Ford

Days before Christmas 1978—the year after he had met President Jimmy Carter at a White House dinner—champion heavyweight boxer Muhammad Ali was surprised in London for the British version of This Is Your Life.

As guests, including members of his family and famous former opponents, flew in from America to pay tribute, Ali said he felt like a little boy opening presents out of a stocking.

Viewers saw the usually in-control boxer caught completely off guard—and the program, transmitted as a Christmas Day special, is still regarded as one of the best in the long-running series.

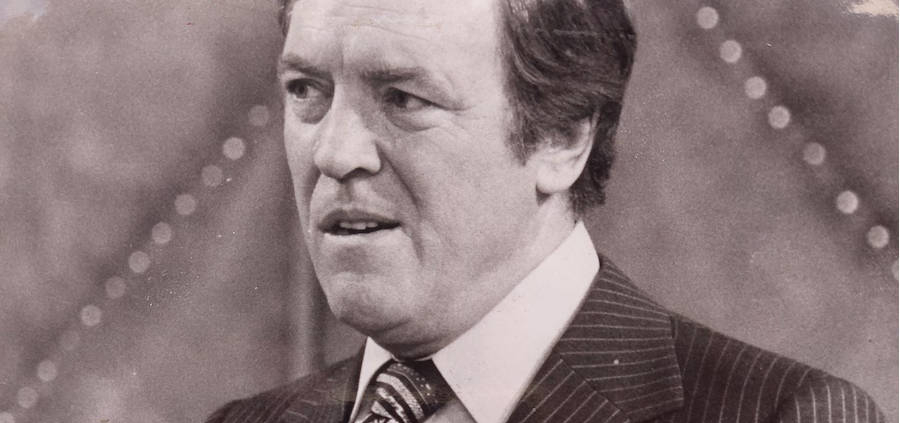

The genial host was Eamonn Andrews, whose birth centenary fell on December 19.

It was Eamonn who met Ralph Edwards and introduced the iconic show to Britain in the ’50s. He ensured its massive success, presenting 730 editions. Many featured top names, including Lord Louis Mountbatten, Admiral of the Fleet, the Earl Mountbatten of Burma, a distant cousin of Queen Elizabeth the Second as well as Prince Philip’s uncle.

Eamonn flew to New York to surprise songwriter Jule Styne, and to Hollywood for shows on musical star Alice Faye and actors Dudley Moore and Christopher Cazenove. But Eamonn always said he preferred telling the stories of the unsung heroes, among them the Irish priest brothers Father Michael and Father Kevin Doheny of the Holy Ghost Congregation, noted for their humanitarian missions in Africa, especially Biafra. Even Mother Teresa made a filmed appearance on their show.

It was a program of surprises, so secrecy was at its heart. When, at 21, I got a job as a researcher, I found Eamonn to be an amiable figurehead. I still remember him sitting like a ship’s captain at the head of a long table as we debated possible subjects confidentially in a room with closed window blinds. He had a commanding presence but not in an overbearing way. He would smile a lot and joke with the team. After being apprised of the progress of certain shows, he might offer one or two suggestions, then leave while the team talked through the ideas in more detail.

One January day, during rehearsals for an edition being recorded that evening, I had to stand in for the unsuspecting subject (a comedy actress) as researchers often did. Just before the theme music struck up and we walked on set together, I heard Eamonn quietly tell a member of the crew that he had come to the studios straight from Mass. It was not the kind of revelation usually heard backstage of a top TV show, but Eamonn wasn’t unnerved by declaring his religious allegiances in the rather irreverent world of light entertainment.

Eamonn and I stayed in touch over the years and, while he must have had a massive postbag, he took care in his responses, showing wisdom, for example, when discussing vocation: “There are many ways of serving and I’m sure you’ll find the best of them,” he once wrote to me.

Eamonn, who had once thought seriously about joining a religious order and becoming a priest, loved attending daily Mass, cared deeply for others, wrote to inmates in prison, and always believed in giving other people a chance. On weekends, he left fame behind and liked nothing more than tucking into his mother’s appetizing steak-and-kidney pie at the Dublin home he’d bought for her.

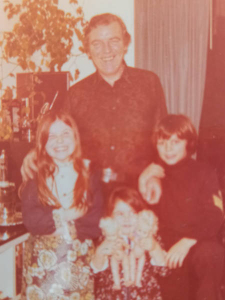

Family was at the heart of Eamonn’s own life. He married Grainne Bourke, the daughter of theatrical impresario and outfitter Lorcan Bourke, in November 1951, at Corpus Christi, Dublin. They had three adopted children.

“Growing up with Mum and Dad was bliss, a little piece of heaven really,” says the eldest, Emma, who still lives in Dublin. “We were so blessed to have ended up where we did. Home was an island, and we were quite private.”

Fergal, who later moved to England, describes Eamonn as “a great father,” a warm and genuinely affectionate man who loved his wife and children. “I always felt loved and safe when I was with him. He was also a wise man and always ready to help anyone. He was very approachable.”

When the youngest, Niamh, looks back, “what immediately comes to mind is what amazing parents they actually were,” she enthuses. “They led me to believe I could do anything, so I always believed I could.”

Eamonn Andrews with his family.

As a father, Eamonn was a very gentle person, as his own father had been. Even if he were annoyed, he never raised his voice or threatened any of them. “He really let us form our own consciences,” said Emma. “If we did something wrong, we’d be sent to our bedrooms to examine our consciences. Then we’d come back and apologize. In a way, it taught us how to reflect on our actions and to apologise graciously. Dad and mum’s watchword was always: Be gracious.”

Niamh, a former air steward who works with children with special needs, recollects that her father encouraged her to have more empathy for other people and be more tolerant of them. “If I said I hated someone at school, he’d say that ‘hate’ was a very strong word. He’d sit me down and tell me to look at it from the other person’s side. I do exactly the same with my own children. He gave me the ability to look at the bigger picture, not to rush in with my own feelings, but to stop and take a moment to think why the other person was reacting the way they were. He had so much empathy.”

Eamonn—whose favorite pieces of music included Nat King Cole’s “Smile Though Your Heart is Breaking” and Johnson Oatman Jr.’s hymn “Count Your Blessings”—always prayed with his children, as many parents did at that time. No matter how late it was, he’d come in and kneel by their beds. He’d then say: “Oíche mhaith agus codladh sámh” (Irish for “Good night, sleep well”). As he was leaving, he’d put his head round the door and add, “Sursum Corda” (Latin for “Lift up your hearts”). To which they would reply: “Habemus ad Dominum’ (“We have lifted them up to the Lord”).

When in Dublin during the week, Eamonn loved going to early Mass at a nearby Carmelite convent in Malahide. On Sundays, he attended the 10 o’clock mass at his local church in Portmarnock. The Andrews always went there as a family, and only when the children reached their late teens were they reluctant to attend.

As a family, they would pray “at the drop of a hat.” If Eamonn had car trouble, he would tell the children to say a Hail Mary; if he needed a parking space, he would pray to the Holy Souls in purgatory at the gates of heaven as they were waiting for a space as well (it seemed to work); and if he lost anything, he would implore the assistance of St Anthony. Eamonn believed the saints and angels were there at every turn, more a humble trust than any form of superstition.

While Eamonn was never a “Holy Joe” as such, his spirituality wove itself in and out of ordinary life, in the Celtic sense of there being a thin line between heaven and earth. There was always a gentle generosity and integrity about him, undoubtedly influenced by his faith.

And he knew his scripture. When trying to teach Emma to be less critical of other people, he would cite the verse: “Look for the beam in your own eye.” He also liked to quote: “What shall it profit a man if he shall gain the whole world and lose his own soul?” which “meant an awful lot time to him, especially in the dark times of his life, when he had to make choices and take the hard path.”

The elder son of William and Margaret Andrews, Eamonn grew up in Synge Street, Dublin, where George Bernard Shaw had been born. Educated initially at the Holy Faith Convent in the Liberties, he was taught catechism by Sister Bonaventure, “a seemingly seven-foot-tall nun” who prepared him for his First Holy Communion at an early age and taught him to read.

Eamonn, an acolyte, moved on to the Christian Brothers’ School, Corpus Christi, where at noon every day the three classes merged to say the Angelus, followed by half an hour’s religious instruction. Eamonn was also expected to sing in the choir, even though he failed to have a note in his head. Nonetheless, the choir won many feiseanna (music festivals) for its renderings of plainchant, and was featured live on Radio Eireann, Eamonn’s first broadcast, listened to by his parents on shared headphones connected to a crystal set, the first time they had a radio in the house.

While working for the Hibernian Insurance Company in Dublin, rising from junior clerk to assistant surveyor, he began in his spare time to make his name as an amateur boxer, radio commentator, playwright, and newspaper columnist. Later he gained fame with his flair for boxing commentaries at the BBC, receiving plaudits for his live coverage from San Francisco of the world heavyweight title fight between US champion Rocky Marciano and Britain’s Don Cockell. It was dubbed “the finest sports commentary ever heard on radio—anywhere.” It was the start of a hugely successful career in broadcasting, with Eamonn becoming, not only a name on everyone’s lips, but also Britain’s highest-paid performer.

But his capacity for unrelenting hard work in high-pressure environments throughout his life may have eventually contributed to a deterioration in his health. Despite the diagnosis of a serious heart disorder, however, he vowed never to miss Mass. In his last days, while chronically fatigued and out of breath, he still managed with assistance to reach the altar of the Brompton Oratory, London, to receive Holy Communion.

The edition of This Is Your Life, which Eamonn watched in a nearby hospital only hours before he died in 1987 at the age of 64, featured Jimmy Cricket, a Catholic comedian from Northern Ireland whose son, Frankie, is a priest. “People warmed to Eamonn’s wholesome genuine approach because he was filled with an air of goodness and people can read into the soul,” said Jimmy. “He was quite revered and loved, a gentleman who made such a mark in those early television days. The fact that my show was the last one he watched from hospital the night before he died was very emotional to discover and, in reflective moments, I do feel a bond with him spiritually.”

At the centenary of his birth, Eamonn was remembered during Mass at the Church of Our Lady of Grace and St. Edward in Chiswick, which he attended when living in London and where today is an icon of the third-century Roman comedian and martyr, St. Genesius, patron saint of actors, in memory of him.

Parishioners there still speak of him fondly. “We felt we knew Eamonn even though we didn’t really—and that’s because he was a real person,” one told me over coffee. “He was open. If anybody spoke to him, he would listen with a smile, not showing signs of wanting to leave.” Although tall, he was always at everyone else’s level, a quality which communicated itself through the screen to those watching him at home.

Emma, Fergal, and Niamh think their father left a powerful legacy, coming from humble beginnings as a £5-a-week insurance clerk and climbing to the top of his profession as an influential television star—”all by himself, through sheer self-belief and confidence.” But they also point out that the genuine affection people had for him has outlived his celebrity status. Says Fergal: “Even to this day, when somebody I have just met finds out he was my father, they genuinely remark on what a lovely man he was and how much they liked him.” ♦

Michael Ford is a biographical writer and ecumenical theologian living in the UK. His features for TAC reflect a lifelong interest in the spiritual and psychological journeys of women and men from all walks of life. He may be contacted at hermitagewithin@gmail.com.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!