For the Lives of the World by Frank Freeman

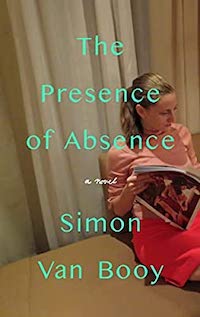

The Presence of Absence: A Novel

by Simon Van Booy

Godine, 2022

$24.95 184 pp.

When I was done reading this haunting, beautiful novel and mulling it over, a passage from the Tao Te Ching by Lao Tzu surfaced in my mind. Something about emptiness, I recalled. Here is “Stanza 11,” from Thomas Merton’s friend and fellow convert John Wu’s translation:

Thirty spokes converge upon a single hub;

it is on the hole in the center that the use of the cart hinges.

We make a vessel from a lump of clay;

it is the empty space within the vessel that makes it useful.

We make door and windows for a room;

but it is these empty spaces that make the room livable.

Thus, while the tangible has advantages,

it is the intangible that makes it useful.

Emptiness makes things useful. A bowl wouldn’t be useful if it wasn’t empty. If a room wasn’t empty to start with, we couldn’t fill it with furniture and paintings and books. If my woodstove hadn’t been empty this morning, I could not have placed wood in it and ignited the wood to heat my shed.

This is, perhaps, what Simon Van Booy means by his enigmatic title The Presence of Absence. Or one of the things he can mean. The novel, about a writer, Max Little, who is dying—we’re never told exactly how, but the implication is of some kind of cancer—consists of two parts: the first called “In Vivo,” or “within the living”; the second, “Ex Vivo,” or “out of the living,” qualified with “Sotto Voce,” or “in a quiet voice.”

This is, perhaps, what Simon Van Booy means by his enigmatic title The Presence of Absence. Or one of the things he can mean. The novel, about a writer, Max Little, who is dying—we’re never told exactly how, but the implication is of some kind of cancer—consists of two parts: the first called “In Vivo,” or “within the living”; the second, “Ex Vivo,” or “out of the living,” qualified with “Sotto Voce,” or “in a quiet voice.”

In the first part, we read Max’s record of his life and illness. He is happily, and realistically, married to Hadley (the story is mostly about her, he says), whom he first encountered in grade school when she rescued him from a bully. She was an excellent tennis player, and one smack from her racket drove the bully away with a cheek that “looked like fleshy graph paper.” She saved him, and this book, Max says, is about how he then had to save her.

Max was being bullied because he was a “Paki.” At age 19, after having abused his wife and son and attacking a police officer, the bully ended up in jail, where he hanged himself. “From his short, violent existence had sprung everything in mine that is beautiful,” Max comments. The bully had died, Max adds, “before we allowed social media to preserve the moments of our lives by stealing them.”

Barbs like that prick out like thorns from the stem of a rose throughout this book, which is not just a meditation on death and married love, but also on the art of fiction.

Van Booy begins Max’s reflections with a warning that this is not your typical novel with a crisis that draws you in, “distracting you long enough to forget you exist outside the book, where—like me—you are dying.” If the reader can take that dose of reality, then maybe she is ready for the next:

And so if contrived disaster is why you’re here—to be diluted by the suffering of others—then I suggest you stop reading and put this book down. Find a parable-style work with a cover that has been purposefully designed to trick you. . . .

In this story, pain is the only reliable proof of happiness.

Max goes on to say that when we read a story, we are engaged in a very powerful form of intimacy: “Stories lead us behind the curtain of somebody else’s life into the deepest chambers of our own.” He adds a bit later, “And though we may never be together in body, this book will ensure that we never part. That you and I, in this moment, are the universe in soft and difficult pieces.” I’m not quite sure what “soft and difficult pieces” means, but it reminds me of Master Oogway in the animated film Kung Fu Panda, who, when he dies, softly disintegrates and flutters off into something like peach blossoms in the wind.

Van Booy’s book is—and this is refreshing in and of itself—a metaphysical one. It is concerned with more-than-this-world realities. And his “answer,” such as it is, is rooted in Eastern philosophy. Max comes to this provisional answer through his wrestling with his imminent death and how to tell Hadley about it. Although Max and Hadley love each other deeply—“It’s not that we fell in love—more like we had always loved each other and were then just remembering”—their love has been purified (though I’m not sure that’s the word Max would use) by the death of their infant son, Adam.

“In the months after Adam’s cremation,” Max writes, “Hadley and I almost split.”

Our near separation was not because we didn’t love each other, but because it hurt to love anything. . . . In the end, we found a way to harness grief to logic: Would baby Adam have wanted his mother and father to suffer because of him? And so, to honor his spirit, we stayed together, and in time realized it was what we wanted, too. . . .

But now you can understand how it was another thing that helped me to cope. Adam was out there somewhere, and soon enough, I would be out there too.

Even though Adam’s death helps Max cope, it also causes him to fear what his imminent death will do to Hadley. So he keeps it to himself for several weeks and goes to counseling to help figure out how to tell her without shattering her. Before the counseling begins, however, he retreats to his and Hadley’s lake house, where he attempts to come to terms with death on his own.

On his third day at the lake house, he is walking on the beach when it begins to rain. “At first I was annoyed, but then stood at the water’s edge and stared at all the thousands of drops melting into the sea,” he reports. Then he has a “realization”:

What I experienced was the awareness of a deeper presence, like a soul—but different in that it was not another self, but something beyond identity and outside of feeling, like an un-self that was not limited by physical or temporal boundaries, a fragment of some larger whole that was neither living nor dead. It simply was the way the universe is.

To put it another way, I understood with certainty that everything I was going through was actually happening to Max. And up until that moment on the sand I had identified solely as Max, believing everything he felt to be things I was feeling; everything he was afraid of, things that were actually frightening and not merely elements of our world beyond Max’s control.

Standing there, a lone figure in the rain, I was released from a kind of spiritual paralysis, and as a result, felt compassion for what Max was going through. He would need my help to get through this experience he had been told was “death.” I must forgive him for being afraid and help him understand that Max was really little more than one of Plato’s shadows, mistaken by all for the thing itself.

This spiritual detachment is not totally sustainable, however. (Moreover, I wonder, would Max describe Adam as “one of Plato’s shadows, mistaken by all for the thing itself”? Are we wave patterns or persons?) Max can get a taste of it by referring to himself in the third person, by remembering, but going back to the beach does not seem to help—and how will this experience help Hadley? Max feels she will not survive his loss “because all the strength a person unknowingly sets aside for that sort of loss had been used up by the loss of our son, Adam.”

Of course, the time between when Max learns he is dying and when he tells Hadley is highly fraught. This is convincingly conveyed in the following passage:

When you are in possession of knowledge that would shatter the person you adore if they knew, you love them more by realizing that every small thing they do—from eating ice cream to laughing at something on television to asking your opinion about a hairstyle—is no longer a small thing but some grand event in the universe.

Another such passage occurs when Max, finally having worked up the nerve to take Hadley out to a restaurant where he will tell her about his illness, smiles to himself as Hadley tells him how to drive better, where to park, and, he hopes, “ask several times if I had locked the car, when she had seen the lights flash and heard the double chirp”:

These rituals of marriage that you learn to accept if you wish the relationship to thrive, I’ve since realized in extremis, are indicators of an uncommon intimacy. Their purpose? The transfiguration of unarticulated fear into shared moments of trust.

What Max had planned so carefully is ruined by an encounter Hadley’s childhood neighbor and his ex-wife, who join Max and Hadley for dinner and, later, coffee at the lake house. This event, and Max’s frustration about it, fits in with something his counselor, Carol, has told him: that he strives too much for idealistic perfection.

We learn that Max has told Carol of his mystical lakeside experience, and she has asked him if he has explored Buddhism. He says he likes Buddhism except for “the robes and ten syllable words,” but what most frustrates him is that all religions teach something said in the Qur’an: “Do not be deceived by the life of this world.”

After the failed dinner, Max—who has been imagining his life “as water cupped, momentarily, from an endless sea that isn’t in the universe but is the universe itself”—goes back to Carol for encouragement. There, in the waiting room, he meets a man named Jeremy who becomes his best friend and helps him to rouse the gumption to finally confide his secret to Hadley. It’s another case of a seeming misfortune—the ruining of Max’s plan—turning out to be the best thing for him.

♦ ♦ ♦

Two further passages in the novel struck me as giving particular insight into Max’s character. The first comes when Max remembers his time as a struggling young writer and when his first short story was accepted for publication in the Bulgarian Review. He books a trip to Paris for himself and Hadley—three days, no frills—and thinks, “My short story had been accepted for publication. And unless the world ended before November, I could never not be a writer.”

That’s how young I was.

In truth, it’s probably safe to say that the greatest writers among us never get published. The ones we know are but a splinter on the tree of the ones we didn’t recognize, or put in prison, or murdered, or feebly rejected with the same scribbled note—Sorry. Not right for us—because their work did not conform to the current fashion.

Max’s observation signals for me the greatest truth about writing: it is worth doing even if you never get published. Andre Dubus once compared the “failed” writer to the minor league ballplayer, who, when asked why he kept playing if he knew he’d never make the majors, said, “Because I love the game.” Jean Rhys expressed a similar idea in an interview with the Paris Review:

All of writing is a huge lake. There are great rivers that feed the lake, like Tolstoy or Dostoyevsky. And then there are mere trickles, like Jean Rhys. All that matters is feeding the lake. I don’t matter. The lake matters. You must keep feeding the lake.

The second passage occurs in the last chapter of “In Vivo.” Just before he dies, Max remembers a time in his childhood when he thought he “belonged somewhere else.” His parents had taken him to a “medieval village where actors dress in period costumes and talk about their crafts to anyone who stops to listen.” He goes on to relate:

There were animals, too, along with plows and carts. But it was the smell of hay baking in the sun that made me certain I was remembering something I couldn’t remember. The feelings were simply beyond anything I could express as a child. It was like the certainty of something without the memory itself—a sense of being haunted.

One day people may be able to explain certain experiences like ghosts or déjá vu. But for you and me it’s like looking through a keyhole into the sun.

Thus, Max Little is open to the possibility of a reality beyond this physical universe.

♦ ♦ ♦

“Ex Vivo,” the second part of the book, takes place eight years later. Max has died, and Hadley is remarried and has a daughter, Maxine. This part of the story is told in a combination of prose and poetry, and is, in a sense, “soft and difficult.”

The language of “Ex Vivo” is both objective and given to flights of poetry. It begins with a description of a day “In the province of autumn, / when everything that lives is falling or / wishes to drop.” Maxine is playing in a pile of leaves in the backyard of a house in New Jersey while Hadley watches from the kitchen window:

Outside, the girl is lying still in the pile—a leaf herself. The mother leans forward, taps on the window, as though trying to part the darkness, still unaware—eight years after his death—that what’s lost is, eventually, given back. But most fail to recognize change as restoration, a perfect geometry beyond the paradox of now: a plant is not a plant, a fly is not a fly, a bird is not a bird.

The next day, the day of his death, Maxine goes to school, and since Halloween draws nigh, ends up promising a friend, Gareth, that she will bring him an owl feather for his costume. Meanwhile Hadley is having a difficult time on this very sad anniversary; even listening to her husband’s words of comfort, she “feels her heart ripping, but only to reveal a new one, which in turn must by torn up.” After describing the coming night—

The curtain of night is falling

and things felt in the day

pain and joy alike

are being disassembled

in order to be built again

tomorrow

—the narrator tells of how Maxine and Hadley talk about the owl feather for Gareth, and about Hadley’s first husband, who Maxine is named after. Maxine asks if Max is now a ghost, and when Hadley doesn’t answer, she asks if she can be Max for Halloween. Hadley doesn’t reply, but later thinks, “And now the time ahead like open fields to be crossed.”

From the window Hadley sees something flash. She and her husband go outside and find a feather, presumably an owl feather. The moment implies that Max, or Max’s “life energy” (a term that he once used to describe his beliefs to his counselor), has guided them. It is a soft ending to a difficult novel—difficult in that it unflinchingly stirs up the fear and heart-pain of love, but also the glory of it, its mysterious ebb and flow. ♦

Frank Freeman’s work has been published in America, Commonweal, Dublin Review of Books, and the Weekly Standard, among others. He lives in Maine with his wife and four children, dog, cat, and four chickens. He hopes to have his books published some fine day.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!