“The God-Haunted Heart”: An Excerpt from “Unruly Saint: Dorothy Day’s Radical Vision and Its Challenge for Our Times”

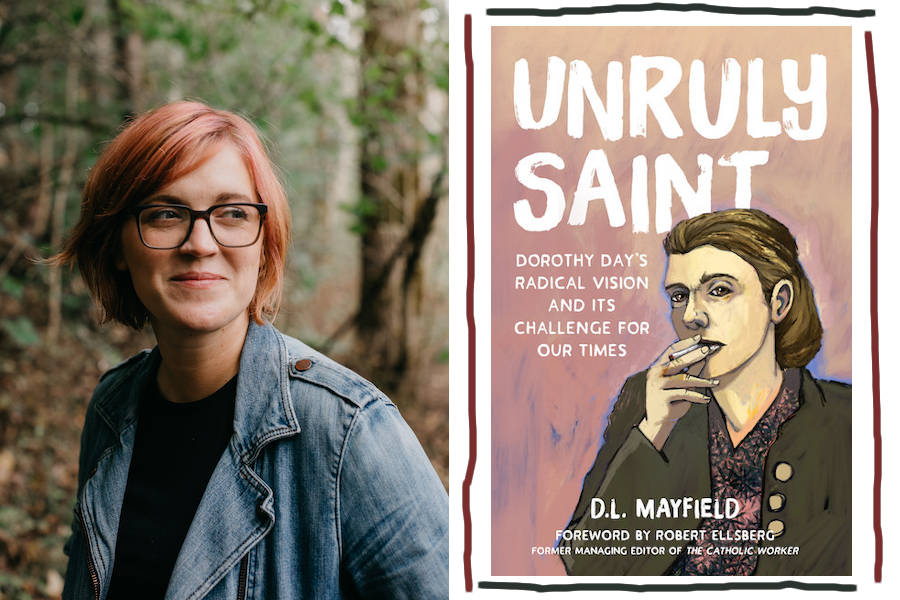

We are pleased to share an excerpt from writer and activist D. L. Mayfield’s recent book on Dorothy Day, Unruly Saint: Dorothy Day’s Radical Vision and Its Challenge for Our Times (Broadleaf Books, 2022). Part biography, part memoir of the author’s ongoing encounter with Dorothy’s life and work, Unruly Saint blends the history of the Catholic Worker movement with theological reflection and connections to contemporary actions for mercy, healing, truth, and justice.

The passage that follows is an account of Dorothy’s return from Washington, DC, where she was covering a hunger march organized by unemployed union workers for Commonweal at the end of 1932. The events as D. L. relates them evoke the feeling of hope, expectancy, and spiritual boldness that characterizes Dorothy’s life and that of the Catholic Worker movement more broadly.

Our special thanks to Jana Nelson of 1517 Media/Broadleaf Books for all her assistance. Readers are encouraged to check out the conversation our friends Elias Crim and Pete Davis of Solidarity Hall had with D. L. on the “Dorothy’s Place” podcast in November; you’ll find the audio for that below—Ed.

The march on Washington ignited a spark within Dorothy. Like so many people, she was forced to ask herself some hard questions about what her chosen religion had to say to the disinherited of the earth: “I watched that ragged horde and thought to myself: these are Christ’s poor. He was one of them. He was a man like other men, and he chose his friends among the ordinary workers.” She described how these men felt as if Christianity as a religion and an institution had betrayed them, and she agreed. Perhaps she was thinking about the Founding Fathers immortalized in white marble at the nation’s Capitol, the pseudo-Christian language surrounding the myth of America—an America that had failed so many people. Perhaps she was thinking about the priests who told hungry people to pray harder, to be better, and maybe they would be blessed. She saved her real wrath not for the communists but for the religious folks who did nothing to step in and help the working man. “Men are not Christian today,” she said, recalling her time at the hunger march. “If they were, this sight would not be possible. Far dearer in the sight of God are these hungry ragged ones, than all those smug, well-fed Christians who sit in their homes cowering in fear about the Communist menace.”

In her questions and anger at religion, an old part of herself had been found and returned to her. And yet she also felt miserably stuck. As I read her words and saw the return to her fiery leftist roots, I sensed the loneliness of a new convert facing the contradictions of putting her faith in action. Her heart was at odds with itself, but what is so beautiful to me about Dorothy Day’s story is how she questioned, interrogated, and ultimately asked God for help in resolving this swirl of questions inside of her. She did not have Catholic friends she could go to for advice. She did not have a strong spiritual community outside of the books she read, where, in her mind, Thomas A. Kempis and St. Therese of Lisieux were her best friends—but they were not as practical for real-time and real-life issues in front of her.

She knew what her communist and leftist friends would advise: forget about God and come join the people. This was something her God-haunted heart simply could not do. But in seeing a vision of the face of Christ in the men marching for basic human rights, she thought perhaps there was a place where she could go to for solace, kinship, and possibly even direction.

On the day after the hunger march ended and the people slowly went back to their lives, waiting and hoping for a better world for them and their families, Dorothy went to the National Shrine in Washington, DC to pray on the Feast of the Immaculate Conception. Today, the National Shrine is the largest Catholic church building in America. But in 1932, it was several years old and just beginning to show its potential as a place of pride for Catholics around the United States.

I imagine what the church that she entered was like, before the basilicas were built, with only the ground-floor crypt church built and one small chapel with a shrine to Mary, the mother of God. This is where Dorothy went to pray. Kneeling before the Mother to whom millions around the world looked for solace, kneeling before the woman who knew what suffering was like and who promised her children that one day it would all be redeemed, Dorothy prayed. She asked for a sign. Please, she begged Mary. Show me a way forward. Open up some way for me to work for the poor and the oppressed. And the day she got home to New York was the day she met Peter Maurin.

After Dorothy left DC and returned home to New York City and to Tamar, something troubled and excited her spirit. When she reached her tenement apartment building, she found an older, rumpled man with crooked glasses on his face waiting for her. His suit of clothes was shoddy, pockets crammed with papers; he talked in rhymes and slogans about demanding a better world. She learned he only owned the possessions on his body and didn’t have more than a nickel to his name. He looked, in other words, much like the men Dorothy had just seen at the march.

Dorothy didn’t know it yet, but that was the day everything changed for her, the day her prayers had been answered. And as usual with Dorothy, it would take a long time to fully understand the miracle of what happened next. ♦

Reprinted with permission from Unruly Saint: Dorothy Day’s Radical Vision and Its Challenge for Our Times by D.L. Mayfield copyright © 2022 Broadleaf Books.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!