The Word Became Flesh and Dwelt Among Us: Jesus for Our Time by Gene Ciarlo

In a New York Times op-ed from June 5, 2025, David Brooks, a long-time regular columnist, composed an essay which set me thinking not only about the direction of world politics today, his subject matter, but also about the direction of the Roman Catholic Church in the world. It is said that two major subjects, taboo in polite social conversation, are religion and politics. In this piece that I offer here, I will tiptoe around the admonition and carefully introduce both politics and religion.

Allow me to quote rather extensively from Brooks’s column, because it spoke to me not only about the political situation in the world today but also of Christianity and, more specifically, Roman Catholic Christianity in our world today. Here is the central thought of the column, “The Democrats’ Problems Are Bigger Than You Think”:

There have been only a few world-shifting political movements over the past century and a half: the totalitarian movement, which led to communist revolutions in places like Russia and China and fascist coups in places like Germany; the welfare state movement, which led in the U.S. to the New Deal; the liberation movement, which led, from the ’60s on, to anti-colonialism, the civil rights movement, feminism and the L.G.B.T.Q. movement; the market liberalism movement, which led to Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher and, in their own contexts, Deng Xiaoping and Mikhail Gorbachev; and finally the global populist movement, which has led to Donald Trump, Viktor Orban, Brexit and, in their own contexts, Narendra Modi, Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping.

The global populist movement took off sometime in the early 2010s. It was driven by a comprehensive sense of social distrust, a firm conviction that the social systems of society were rigged, corrupted and malevolent.

There is the big picture set out in very broad historical strokes. Today, according to Brooks, we, kicking and screaming, are entering into the global populist movement, and it is not fun. That is the political scene as understood and expressed by one writer whose opinion I value to no small degree, perhaps because I consider him a deeply spiritual man.

Simultaneous with our secular scenario, we are living in the onset of a major religious scene, not yet full blown but still far advanced. It is the decline of institutional religion as we have known it for centuries. More specifically I refer to the decline of Roman Catholicism. Waning religiosity was hardly evident during the recent conclave in Rome that elected the new American pope, Leo XIV. From all appearances—and the world was watching—there was no indication of decline in the Western world’s religious spirit. It was a gala religious event spilling into our daily feed of social and political realities. Worlds were colliding in an upbeat way. The Middle Ages poured into the 21st century in grand style.

Is that the real state of the Catholic Church in the world among the billions who claim but do not necessarily profess the Catholic faith? It is a rhetorical question. The number of regular worshippers throughout the world, at Sunday worship in particular, is far smaller than the 1.4 billion Catholics who are counted in statistical format. What has happened in the last 30 or so years that has changed the face of religious belief and practice throughout the Catholic world? The simple answer suggests that theological reasoning and the translation of theology into popular catechetical form that has come down to the people who used to populate church pews is no longer viable, believable, and acceptable in our evolved, 21st-century educated environment.

Nor is our secular world easily compliant and open to embrace the word of the usual news outlets trumpeting the daily politics of our world. Truth be told, to a modern educated populace the standard broadcasts and telecasts are no longer the sources of information that those who want to be “in the know” turn to if they are seriously interested in uncovering the “real” truth. Truth in our social and political world today is elusive. Trumpet that as a new aphorism for our day and age.

Getting back to the Christian churches’ teachings, the problem indeed lies in the theological formulation and subsequently the popular understanding of what is put forth about Christianity, and more specifically about Jesus the Christ. In other words, the very theological understanding of God, creation, salvation, redemption, sanctification, and all of the major signposts leading one to what has been known as the kingdom of God and matters of the spirit are questionable at best.

To name just one primary and fundamental source for our beliefs and practices, allow me to quote from the latest authorized, revised 2018 edition of the Catechism of the Catholic Church, article 390: “The account of the fall in Genesis 3 uses figurative language, but affirms a primeval event, a deed that took place at the beginning of the history of man. Revelation gives us the certainty of faith that the whole of human history is marked by the original fault freely committed by our first parents.” Truth be told, from a scientific point of view, we humans did not come into a harmonious world that we wrecked by eating the forbidden fruit, regardless of how symbolic and “modernized” we may now identify that fruit. This core belief about how evil entered the world, fundamental and basic, demonstrates forcefully how our theology of human life has been left in the dust of time, progress, and our ability to assimilate into our religious faith and practice what has developed scientifically over the centuries.

This holds true for so many of our “teachings” that form the foundation of our theology and, in turn, of our lifestyle: how we propose to live our lives in view of the stories that are supposed to mold us to God and all of humanity and creation. In sum, we Catholics are expected to believe and accept as the groundwork of our faith, and therefore our actions, nothing short of archaic fairy tales. Make no mistake: at one time they were valid explanations of the mysteries of the faith, but in view of scientific understanding and progress, or just simply the development of our minds, intellects, and general progress in every field of science, life, and love, we can no longer accept the simplistic explanations of how we are grace-filled men and women destined for eternal life in the kingdom of God. The words alone suggest that we are out of touch with reality, terrestrial or otherworldly.

The redemption theme is fundamental to Christianity. We are a fallen race needing to be saved, and Jesus becomes the means by which we are saved. In order to do that he had to be God because one man alone, dead or alive, cannot save the human race. One theological point leads to another—and then in the fourth century, through various ecumenical councils, a whole theology of redemption necessarily developed for the sake of logic. In the process of rationalization, Jesus is made the “alpha human,” an almost inhuman God figure who is the source of our salvation. The educated world of today will not buy that. It is an archaic and rationalized way of trying to make Jesus the savior and redeemer of a fallen human race.

It cannot be that simplistic. According to the gospel stories of Mathew, Mark, and Luke—not according to any theological interpretation but according to the gospels themselves, with all their contradictions and imperfections—Jesus by word and example was and is a man, a human being whose primary mission was to show us how to live our lives here on earth. We have become hung up on words and concepts like redemption and salvation, as if Jesus’s death and resurrection were the great theological reality that unlocked for us the kingdom of heaven. That is what our theology teaches us. His life, what he did and said, and how he lived and interacted with people was and is the lesson that stands head and shoulders above any theological maxim about being “saved” from sin and death and the afterlife. The latter is St. Paul’s theology and much of St. John’s. It is not Jesus’s theology, nor what theologians have churned out above and beyond Paul and John over the centuries.

Faith and Purpose

Tomorrow’s Catholic by Michael Morwood is a small tome, copyright 1997, that stirred up a bit of a fuss at the time it was published but did not have the impact that the work of major theologians would have had on the Catholic world had they said similar things. The closest contenders for censure would be Edward Schillebeeckx or Karl Rahner, who had been very progressive in their thinking and theologizing to the extent that Rome had shaken a finger or two in their direction over the years. They have both since passed from this life.

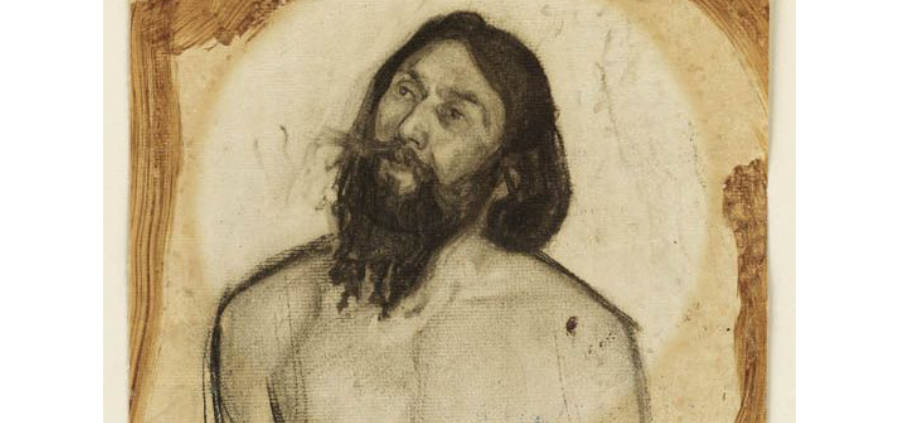

Henry Ossawa Tanner, “Mary Magdalene Washing the Feet of Christ,” c. 1896-1936

Morwood has said some wonderful things about Jesus and the direction in which modern, progressive theology about the Son of God and redemption, salvation and sanctification have taken us. I quote from his book:

Jesus understood his ministry in terms of setting people free. We need to be clear about this. His life and death were not concerned with changing God’s mind or winning back God’s friendship. Rather, his living and dying were about changing people’s minds and hearts. This is a different context in which to understand salvation. In Jesus’ preaching, salvation is connected with setting people free from fear, ignorance, and darkness, and with changing the way they imaged and thought about God and themselves.

In another place he says, “Jesus’ work of salvation directly addressed the issues of fear, ignorance, and darkness which clouded the religious thinking and images of the people.” Relative to that, in considering the place of human suffering in this world, he writes:

In this context we need to contemplate the passion of Jesus. It was not a burden God asked Jesus to bear to “make up” for our sins. It was not a price to be paid so that God would relent and allow us back into God’s friendship. What image of God is at the heart of such thinking? No, the passion is rather the reality of where human existence led this man. And, like us, in the harsher realities of life his faith perspective was tested to the limits.

Allow me just another example or two that might set theology in the direction of a modern framework so that we can think thoughts and digest ideas that are consonant with our time and our understanding of life, love, suffering, hope, salvation, redemption, and God-with-us today. To repeat, our catechesis and our theology as it stands now are archaic, outmoded, and unacceptable to an educated, enlightened people. We have to bring them into the modern world if they are not to be relegated to the annals of idol worship. Hear Morwood once more, regarding the way we should see Jesus and how we should relate to him:

When the accent is put on Jesus’ divinity, as someone unlike us, we miss the whole point of his life. He was not trying to win back God’s friendship or get us a place in heaven. He was desperately trying to get people to believe in God’s loving presence with them. As we saw, he tried to “save” us by setting us free from thoughts and images about God that imprisoned us. He tried to be a light in the darkness.

Finally, Morwood comes to his own defense lest he be misunderstood about his own faith and the purpose of his work:

This is not an attack on Christian faith. It is an assertion that Christian faith has been packaged in a particular way, in particular thought patterns that have been set in concrete and that the time has come to reexamine, with open minds, the fundamentals of our faith and to try expressing them in ways that are relevant to today’s worldview.

A Cosmic God

We Catholic Christians can take pride in the pomp and ceremony that surrounded the recent installation of Robert Prevost as Pope Leo XIV. Humanity needs that kind of lift now and then, so it is said. But is worldly pomp compatible with the spirit and message of Jesus as told over and over in the gospels? On the one hand it may be said that the world will not listen nor give us a second glance if we do not fit into the style cultivated by our human intelligence and creativity, impacting for better or worse our world of 2025. On the other hand, do the followers of Jesus the Christ have to play the world’s game if they want to be acknowledged and given a voice socially, politically, and scientifically? There answer is a resounding no, but with reservations, explanations, and caveats. Our theology must speak the truth for our time. It cannot be lost in the past, the product of another age which no longer makes sense. St. Francis of Assisi was successful without the pomp and ceremony within the church, even in that 13th-century environment of church-and-state tension. The saving grace of St. Francis and his followers was that he embraced the earth so that there was really no dichotomy between it and heaven. His theology was not really new. In fact, it bordered on pantheism or nature worship, as if his God was the sum total of nature.

Placing that idea of the unity and bond between heaven and earth, the sacred and the profane, the words of the paleontologist priest Teilhard de Chardin come to me and impress a stamp of clarity on the concept. In his book Hymn of the Universe, Chardin makes the Mass, the celebration of Eucharist, cosmic and all inclusive. “Over every living thing which is to spring up, to grow, to flower, to ripen during this day say again the words: This is my Body. And over every death-force which waits in readiness to corrode, to wither, to cut down, speak again your commanding words which express the supreme mystery of faith: This is my Blood.” All is divinity. Christianity is cosmic and timeless, not bound to intellectual theologizing and circumscribed by time and space.

We are not pantheists but, as Chardin, would have it, we are panentheists. The universe and beyond is shot through with divinity, the elusive God whom people say they love. Love Jesus, the manifestation in flesh and blood of that divine presence, the symbol of the unique God, the One who makes the universe holy and ultimately, eventually, whole. Jesus was and is a manifestation of that universal holiness which is the face of God. Jesus alone is loveable, not a faceless God whom people say they love. As Orthodox theology would have it, in the pithy and powerful phrase attributed to St. Athanasius, “God became human so that humanity might become God.” The human God, Jesus, is the one whom we can rightly love and follow. ♦

Gene Ciarlo is a priest no longer active in the ministry. Ordained from the American College, University of Louvain, Belgium, he spent most of his ministry in parish life. After receiving a master’s degree in liturgical studies from Notre Dame University he returned to his alma mater in Louvain as director of liturgy and homiletics. Gene lives in Vermont, where everything is gracefully green when it is not solemnly white.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!