The Faithfulness of Black Catholics in the Promise of Christ Resurrected by Leslye Colvin

What does it mean to be Black and Catholic? Servant of God Sister Thea Bowman, FSPA, asked and reflected on this question while addressing the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops in 1989. Thirty-five years later, Dr. David Robinson-Morris asks this question again in the 3,000 hours of interviews that shaped FADICA’s 2024 report “And the Walls Came Tumbling Down: A Report on U.S. Black Catholic Dreams toward a Just Church.” I periodically discern the question myself, as a woman who embraces my Black and Catholic identities. There is spiritual longing in the asking.

I was born in a Black body in a racially segregated society. In the mid-1960s, before my eighth birthday, my family entered the Catholic Church in our rural hometown’s only parish. I cannot explain why it happened, but the parish welcomed us. My parents became involved in a number of ministries, and leaders in the parish and deanery. Years would pass before I came to appreciate and understand why my parents would sometimes speak the obvious and remind my siblings and me of our Black identity. In 2025, my gratitude for this reminder abounds as it affirms my identity and experiences in these disturbing times.

My family’s experience of welcome in a predominantly white parish is not shared by all in similar situations. As a collective, Black Catholics have experienced varying degrees of welcome and the opportunity to thrive in our respective parishes, schools, seminaries, dioceses, and chanceries. In my childhood parish, I remember the challenges faced by a new parishioner who had grown up in a Black parish. Even after having her children baptized, she did not thrive there and eventually joined another church. How many of us leave the Catholic Church because we long to thrive in community?

Bowman faithfully and courageously modeled for us the integration of her Black and Catholic identities. Though the church was and is vulnerable to racism, she found a way to persevere and thrive. As a result, the church benefited enormously. This is how she answered the question about her Black Catholic identity during her famous 1989 speech to the bishops: “It means that I come to my church fully functioning. I bring myself, my Black self, all that I am, all that I have, all that I hope to become. I bring my whole history, my traditions, my experience, my culture, my African-American song and dance and gesture and movement and teaching and preaching and healing and responsibility as gift to the Church.” She challenged her brother bishops to do more even as her health declined. Heeding her call as God’s prophet in their midst required the bishops to move beyond the privilege of the male episcopacy and, for most, the privilege of white body supremacy.

Saint Paul’s teaching that following Christ transcends social divisions appears to be irrelevant to the status quo. Those of us who carry the generational trauma perpetuated by anti-Black racism and white supremacy have many unfulfilled dreams regarding the church’s failure to eradicate the systems designed to privilege our siblings in white bodies. It is beyond me that so many choose to ignore the discomfort of their privilege; the discomfort of hearing the truth and learning one has been benefiting from systemic privileging. This stalemate stymies the movement of the Holy Spirit and our collective spiritual growth for all of us. To unleash the Spirit within our church, we—the Body of Christ—need to welcome the discomfort of difficult dialogues about privilege and power as part of a long-term commitment to reconstructing just systems.

Our leadership must give faithful attention to creating safe spaces in which Black Catholics can thrive. Catholic institutions must learn to recognize and resist the sins of anti-Black racism and white supremacy. Are they willing to do so? Parishes, schools, and seminaries must teach in catechetical formation that these grave sins are based on gross distortions of Christ Jesus, the gospels, and Catholic Social Teaching. They are a systemic denial of Imago Dei requiring undoing across multiple generations.

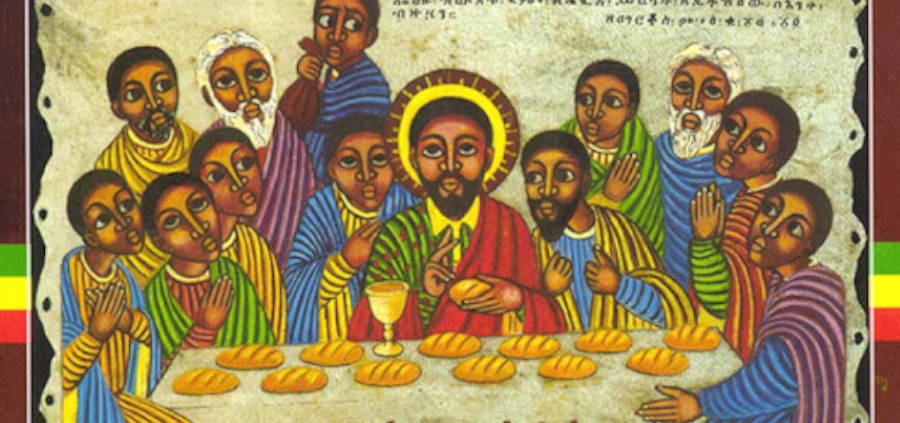

The FADICA report recommends a focus on “Gospel-informed radical love.” Pope Francis consistently called us to encounter each other in Christ beyond the barriers constructed to separate us. Similarly, Pope Leo XIV teaches, “In the One, we are one.” The Most Holy Sacrament of the Eucharist is profound in how it brings us together to share a sacred meal. This bread, broken and shared, is the Resurrected Christ. Ponder the thought for a moment. The Eucharistic bread is the Resurrected Christ. This is our belief. This is our faith. United in this life-giving belief that is inconsistent with systems of oppression and privilege, why are we all not thriving?

By the rite of baptism, we are called to be mediator, prophet, and royalty. We know well Moses’s God-given command to Pharaoh, “Let my people go.” Like the Hebrew people, we know the dehumanizing trauma of bondage. Not unlike Jesus, we know the bitter taste of oppressive systems. Even so, we have experienced God’s abiding presence, and heard the voices of God’s prophets. In our thriving, all of the church thrives. ♦

Leslye Colvin is a writer and activist based in Alabama, the ancestral lands of the Muscogee. Her works include Seeking Wisdom’s Light: Reflections for Advent and Christmas 2024. Find more at her Substack, “Leslye’s Labyrinth,” here.

Enjoyed your article. So well expressed. “Let my people go” speaks so well of the Father’s cry for all his children where there has been a culture of oppression.

Blessings

Maree