God Is Love, without Condition by Gene Ciarlo

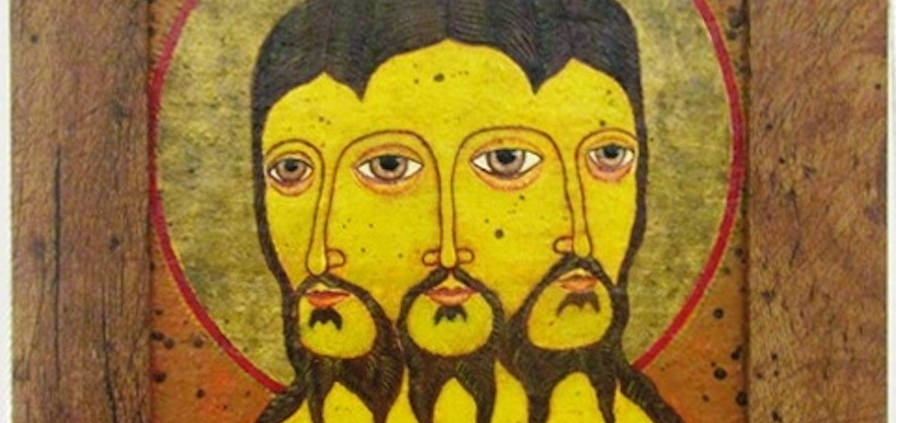

If we are made in the image and likeness of God, then we should easily be able to pray to God, since God must be like one of us. In fact, God must be a person, as we say that God is a Trinity of three Persons: Father, Son, and Spirit. The Council of Nicea knew about this when the Fathers formulated the Creed in the year 325. It is a dogma of the faith, and therefore not to be questioned. But even today, how much do we really know about the Trinity as we keep probing into the unknowable? I am about to delve a little more deeply into a way of trying to image God who may not, in fact, be one of us.

The three-Persons-in-one formulation for understanding and trying to define God will not encounter any serious challenge from Christian evangelicals or fundamentalists, including many Roman Catholics, nor any others who want to take this concept of the Trinity and the words of the Bible as literally, divinely inspired and therefore inerrant. But there are other sides to this story.

For one particular explanation of biblical events, I turn to the existentialist philosopher and Lutheran theologian Paul Tillich and his classic book Dynamics of Faith. But first of all, for the sake of clarity, I want to define the term myth, which comes up often in biblical exegesis. What is a myth from a biblical perspective? It is a story that is making a point above and beyond the story itself. The point, the truth, is not the story but its interpretation. Tillich puts it this way:

[A]ll the stories in which divine-human interactions are told are considered as mythological in character, and objects of demythologization. . . . The resistance against demythologization expresses itself in “literalism.” The symbols and myths are understood in their immediate meaning. The material, taken from nature and history, is used in its proper sense. The character of the symbol to point beyond itself to something else is disregarded. Creation is taken as a magic act which happened once upon a time. The fall of Adam is localized on a special geographical point and attributed to a human individual. The virgin birth of the Messiah is understood in biological terms, resurrection and ascension as physical events, the second coming of the Christ as a telluric, or cosmic, catastrophe. The presupposition of such literalism is that God is a being, acting in time and space, dwelling in a special place, affecting the course of events and being affected by them like any other being in the universe. Literalism deprives God of his ultimacy and, religiously speaking, of his majesty. It draws him down to the level of that which is not ultimate, the finite and conditional. . . . Faith, if it takes its symbols literally, becomes idolatrous!”

Let us ponder the idea of God from a totally different point of view, one that does not isolate God as a person just like you and me, but is neither masculine nor feminine. It seems that this is the only attribute of God that we have allowed to change in our minds. Many people still consider God a person, but they don’t dare say “him” or “her.” But this is a matter of semantics. In all honesty, for most of us, what else is different about the “personhood” of God in our thinking and imagining? Nothing. It is a word game.

Marcus Borg, a renowned Scripture scholar and author of numerous books on the interpretation and understanding of the New Testament, is my “go-to” exegete for things biblical. In one of his earlier books, The God We Never Knew, he says, “I have realized that one may be an atheist regarding the God of supernatural theism and yet be a believer in God conceptualized another way, namely in the way offered by panentheism. This is the God I never knew.”

That is cryptic. What is this way of understanding God that is called panentheism, the God whom Borg finally comes to know? Let’s break up the word so that it becomes more intelligible: pan means “everything,” en must be “in,” and theism makes reference to theos, which is Greek for God. And, of course, an “ism” is a belief or practice. So panentheism must be a belief that everything is in God or God is in everything. Close but not quite. It needs some clarifying and explaining, which is the tedious and delicate part.

Borg was on a journey of discovery in the early years of his life, into his thirties. About these early years he says, “I now see that the concept of God that I took for granted was in fact a serious misunderstanding that made it impossible for me to take seriously that God was real.” The “panentheism” concept proffered in the works of Teilhard de Chardin, the Jesuit priest, paleontologist, and writer, affected Borg’s thinking about God and brought him to the threshold of belief.

This summons us to go back to perhaps the most famous work of Père Teilhard that expresses in profound and intense concepts his idea of God. Mark well that Chardin did not coin the term “panentheism.” In a previous essay I stated misleadingly that he had. He didn’t coin the term; he conceived the idea, and other thinkers and writers gave it the name which denotes that God is the interpenetration and evolutionary convergence of God and the universe. It is a summation in one word that admirers of the Jesuit priest invented to conceptually concentrate his ideas.

“Interpenetration and evolutionary convergence” requires careful and precise explanation. It is important to go to the source and quote the man who developed this fascinating concept of God and the divine. We must start with three very simple but profound words from the First Letter of John, which really capture everything that Teilhard is saying in his idea and explanation of God: “Anyone who does not love does not know God, because God is love” (1 John 4:8).

In The Phenomenon of Man, Teilhard does not try to define God. He describes God by describing Love:

Considered in its full biological reality, love—that is to say, the affinity of being with being—is not peculiar to man. It is a general property of all life and as such it embraces, in its varieties and degrees, all the forms successively adopted by organized matter.

He says further on:

By rights, to be certain of its presence in ourselves, we should assume its presence, at least in an inchoate form, in everything that is. . . . Love in all its subtleties is nothing more, and nothing less, than the more or less direct trace marked on the heart of the element by the psychical convergence of the universe upon itself. . . . Love alone is capable of uniting living beings in such a way as to complete and fulfill them, for it alone takes them and joins them by what is deepest in themselves. This is a fact of daily experience. At what moment do lovers come into the most complete possession of themselves if not when they say they are lost in each other?

If it is claimed that “a universal love is impossible,” Teilhard continues,

how can we account for that irresistible instinct in our hearts which leads us towards unity whenever and in whatever direction our passions are stirred? A sense of the universe, a sense of the all, the nostalgia which seizes us when confronted by nature, beauty, music—these seem to be an expectation and awareness of a Great Presence.

Panentheism: God in all, that divinity is the Alpha and the Omega of everything, the beginning and the end. Is this God? Is God the sum total of everything in the natural world? Yes and no. Yes, with a major reservation. Père Teilhard does not identify God with all that is, all that loves. That is pantheism. He does not try to identify or define God except to tell the story that everything that exists bears the love of, from, by, and with God, the God who is indescribable and not to be circumscribed in any way. God is the Great Presence, the Great Unknown and Unknowable in our human condition. God is totally other than and apart from God’s so-called creation, understood as through the evolutionary process.

Here is the incredible and amazing key: It would seem to me that we pray to and love God only when we learn to love and love deeply. It is to put on and dwell in the condition of love. First of all, it happens in our hearts through practice, and gradually, like an ocean tide, it becomes who we are. It overwhelms us. As God is love, we must gradually over a lifetime become lovers of everything in the living universe, for everything is of God. You can feel love in itself, even without applying it to this person or that as part of nature. It is a sense of being “in love.” I’m conjecturing now, in this halting explanation; personally, I am not there. Even people who are “experts” on Chardin often find his concepts challenging.

All things considered, relative to the above quotes and ideas, how do you pray to a God that is described in a panentheistic world? My conclusion is that God is not prayed to, not with words and in “prayerful moments” as that might be commonly understood. God is prayed to in learning to and growing in love. The more one senses love in his and her heart, mind, actions—whole sitz im leben and daily life experiences—the more is one, in fact, loving God. There is no need to think specific thoughts and say, “God, I love you.” Your love for God is in living love for all that is loveable. ♦

Gene Ciarlo is a priest no longer active in the ministry. Ordained from the American College, University of Louvain, Belgium, he spent most of his ministry in parish life. After receiving a master’s degree in liturgical studies from Notre Dame University he returned to his alma mater in Louvain as director of liturgy and homiletics. Gene lives in Vermont, where everything is gracefully green when it is not solemnly white.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!