God Is Love, on Condition by Gene Ciarlo

I begin with a quote from The Four Loves by C. S. Lewis. It’s an old publication, to be sure, but its message is timeless. It speaks volumes to our day and our times about love:

To love at all is to be vulnerable. Love anything, and your heart will certainly be wrung and possibly be broken. If you want to make sure of keeping it intact, you must give your heart to no one, not even to an animal. Wrap it carefully round with hobbies and little luxuries; avoid all entanglements; lock it up safe in the casket or coffin of your selfishness. But in that casket—safe, dark, motionless, airless—it will change. It will not be broken, it will become unbreakable, impenetrable, irredeemable. The alternative to tragedy, or at least to the risk of tragedy is damnation. The only place outside Heaven where you can be perfectly safe from all the dangers and perturbations of love is Hell.

That is a pithy, powerful statement that speaks almost violently to every day and every age about love and how important it is in every human life. It makes the Paul Simon hit “I Am a Rock” sound anemic: “I touch no one and no one touches me. I am a rock, I am an island. And a rock feels no pain. And an island never cries.”

At some times in our lives, and even in our world, love speaks louder than at other times. I see the 2020s in these United States, and throughout the world, as times of darkness and separateness, dividedness and mutual hostility, even more so than during the times of world wars, because now our planet, through communication and interaction, has become very small and intimate. And in this smallness we are experiencing a world of hatred, an absence of love and caring. Look at Gaza. Where can such a mind-and-heart-set like this lead? What savior will descend upon the world and say to us, again, “Love one another as I have loved you?” Need I quote the source? Was it all in vain?

There have been volumes written about love, songs sung, wars fought, won and lost over love. It seems that there are two extremes that humanity continues to wage and endure, and yet we carry on. The first is the abominable, destructive, and horrible thing that we humans, regardless of our advanced technology and now AI, never grow out of. It is war. The second reality that we keep struggling over is less tangible, but it vies for dominance in a war-torn world. That is love. No, I do not cite love and hate, which seem to be the more logical opposites. I say love and war because war is the tangible expression of hatred, and I want us to see and understand the horror of the tangible.

Right from the beginning, Lewis, in his book, says that “A man’s [or woman’s] spiritual health is exactly proportional to his [her] love for God.” Think about it: How is a person healthy spiritually? The answer is the subject matter of his book: love. Lewis cites two kinds of love: “need love” and “gift love.” Need love is what a lot of us work with, perhaps on a daily basis. We humans are weak and needy; we get sick, we get hurt physically, mentally and emotionally. Where do we turn in our need? In addition to medical treatment, if you are a believer you may turn to God. Prayers of petition storm the heavens, to be sure, on a minute-by-minute, second-by-second basis in every corner of the globe. Think of how humanity assaults heaven, begging for divine guidance and help. “Please, God!” That is need love, according to Lewis. But is it the epitome of love?

The other is gift love. Gift love is love with no strings attached. It is totally unselfish, not seeking anything in return. Aristotle, in the fourth century BCE, called it agape and defined it as totally unselfish and other-centered. For whom do we have an agape kind of love? I would say that the love between two people can be an agape love, even though we might think of it first as eros, or desire and physical intimacy. But I am certain that even where two people love each other with great physical passion, they can also love each other unconditionally, love for love’s sake. That, indeed, is a love to be sought after and cherished.

I have often said, more to myself than to anyone else, that one cannot really love God. Is that shocking? Let us go back to the statement that started this discussion: “A [person’s] spiritual health is exactly proportional to their love for God.” People talk all the time about how they love God, and I don’t believe it. Is it need love? Is it gift love? I think that primarily, in the early growing stages of spiritual life, it is need love; we need God to be there for us. So instead of saying “I love God,” perhaps most people who believe and worship God ought to say, “I need God,” and forget the love part until they can work to grow into it. When you are down and out, you may lift up your head and shout to God, ‘Help me!” or you can play the atheist and just confess helplessness. In that regard I quote JoAnn Worley in the old TV series Laugh-In: “When you’re down and out, lift up your head and shout, ‘I’m down and out!’” In which case there is no recourse. That is really helplessness and despair.

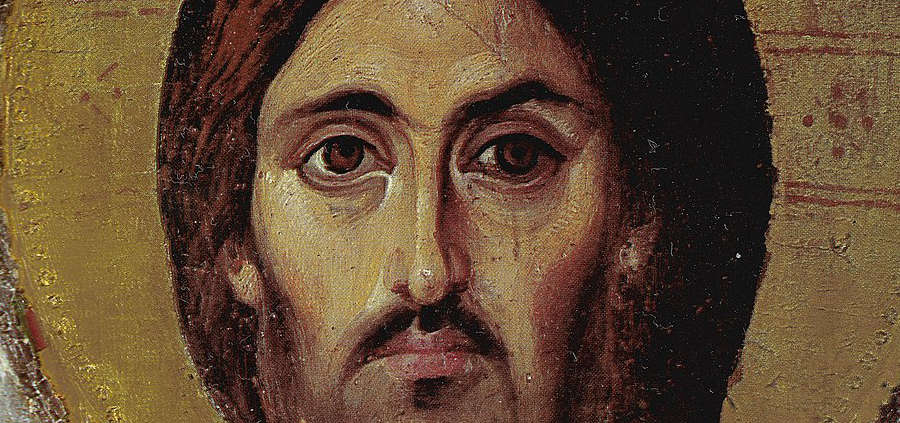

There is another possibility, and it is rare. It is to have a disinterested love for God. I am compelled to quote the First Letter of John in this regard: “But if a man says, ‘I love God,’ while hating his brother, he is a liar. If he does not love the brother whom he has seen, it cannot be that he loves God whom he has not seen” (1 John 4:20). Lewis says that a disinterested love for God is very, very rare. I say that it is impossible. I cannot say that I love God, truly. I don’t know God well enough to love God even in a disinterested way. I love Jesus. I can almost see Jesus; I hear him, I speak to him on a daily basis, I am told about him, even if only in bits and pieces and through hearsay. We call those hearsay texts the canon of the New Testament. It sounds blasphemous to say that I don’t love God because a God-fearing person who has faith in God, worships and believes in their Christian faith principles, loves God. What is the definition of love in that circumstance? Is it Aristotelian eros, philia, or agape, each in its varying degrees? Or is it supposed to be agape, that totally selfless love that is all about “the other,” and not about me at all?

Let us look at it another way. St. John says, “God is love.” They are synonyms; the two are one. Perhaps that might lead me to look at everything in this world as coterminous with the love which is God. Teilhard de Chardin, the priest-paleontologist, called it panentheism. Not pantheism, which equates God with all of creation, or nature if you prefer. Panentheism, according to one definition, is the interpenetration and evolutionary convergence of God and the world. But the critical part is that God is not absorbed into or identical with the universe. God is still God who is love. God is intimately present in all of creation, yet God is totally other, God is transcendent. It may be difficult to wrap our head around that one.

The question now is: Can I love God if I can envision all that I perceive in nature as more than a mere reflection of God, a kind of panentheism? In this way I can love God and know that God is love. Lewis says it this way: “Created glory gives us hints of the Uncreated.” This is not exactly panentheism, but hints at it.

The term “love” is thrown around much too casually. There are varying definitions and degrees of love. No one loves their country because it is great but because it is theirs. Lewis says, “The actual history of every country is full of shabby and even shameful doings.” So true, even in the United States. I love my country because it is mine. No one loves the Catholic Church because it is great, flawless, and without sin. I love the church because it is mine, it is my religion. Thus there are different definitions of love. The kind of love equated with God is the epitome of love.

Another sentence from Lewis strikes me deeply: “We picture lovers face to face but friends side by side.” Friends, in other words, look ahead at some sort of independent future for each of them. Lovers face to face go ahead together; they are one, and one can say to the other, “You are my other self.” That is not only love, but also that truth, beauty, and goodness which, according to St. Thomas Aquinas, are fundamental aspects of reality that relate to all things and point them towards God.

Speaking hyperbolically and fantastically, I want someday to be face to face with God. ♦

Gene Ciarlo is a priest no longer active in the ministry. Ordained from the American College, University of Louvain, Belgium, he spent most of his ministry in parish life. After receiving a master’s degree in liturgical studies from Notre Dame University he returned to his alma mater in Louvain as director of liturgy and homiletics. Gene lives in Vermont, where everything is gracefully green when it is not solemnly white.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!