“Wounded Healer”: How Helpful Is This as a Paradigm for Those Teaching and Working in Catholic Education Today? by David Torevell

Are any of us without wounds—physical, emotional, psychological, or spiritual? Surely not. To be human is to be wounded. Wounds may be caused by others or by events which harm and scar us. They can also viscerally affect our bodies and our minds. They may occur due to personal circumstances beyond our control (e.g., loneliness, bereavement, illness, anxiety, sexual betrayal), or because of devastating geopolitical events like war or natural disasters which deeply affect our sense of equilibrium and balance.

Hearing and watching the daily news can be very wounding indeed (e.g., Gaza, Ukraine, the US). Often wounds are borne for a considerable amount of time, sometimes even until death. Inevitably, they can also instill feelings of revenge on those whom victims perceive to have caused their wounds. However, I think the important question to ask ourselves, especially for those teaching and working in Catholic education, is this: Can we use our wounds in a creative and beneficial manner for the good of our pupils and those with whom we work? Or, to put it more starkly, can our wounds be the basis of actual healing for others and, indeed, for ourselves? I want to answer “yes” to this question and suggest that the notion of the wounded healer is a helpful paradigm to be explored by those working in Catholic schools, colleges, and universities at the present time. Why is this the case?

Key Biblical Texts

Let me start by briefly examining key biblical texts and references on the notion of the wounded healer, in particular Isaiah 53:5 and a selection of New Testament references to wounds, those endured by Christ himself in particular. (The book of Lamentations would also be a good addition if we had the space to pursue this astonishing text.) Later in the piece, I will consider insights from the 20th-century spiritual writer Henri Nouwen and from the contemporary Cistercian monk Eric Varden, both of whom have considered this issue at length and in depth.

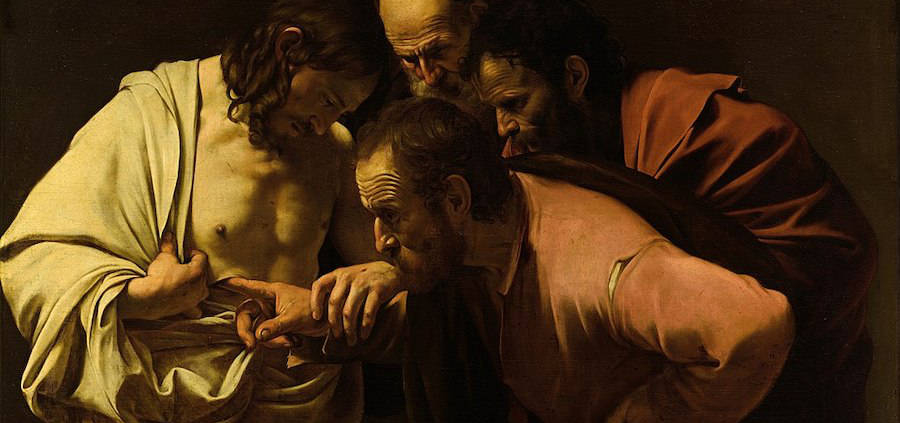

Verses from the prophet Isaiah, chapter 53, are read aloud during the Easter Vigil service. Verse 5 is the one I wish to focus on: “He was bruised for our iniquities; upon him was the chastisement that made us whole, and with his wounds we are healed.” This Old Testament teaching is extended (in both pre- and post-resurrection accounts) in the New Testament and refers to the wounds endured by Christ during his crucifixion. They allude to the four nail-marks in his feet and hands and the lance wound in his side made by the soldier’s spear. All four gospels mention these nails. John 19:34 tells of the soldier who pierced Jesus’s side with a spear, from which blood and water flowed. The description of the story of “doubting Thomas” in John 20:25-29 expresses Thomas’s incredulity in the resurrection in graphically physical terms: until he can actually see the nail-marks in Jesus’s hands and put his own hand in his side, Thomas refuses to believe. Caravaggio’s portrayal of this fleshy encounter captures well this remarkable incident.

Further post-resurrection appearances highlight the wounded body of the Savior. For example, in Luke 24:39 Jesus shows his hands and feet to his disciples, proving he is not a spirit. And in 1 Peter 2:24 the author reiterates the redemptive message of Isaiah 53:5: “He himself bore our sins in his body on the tree, that we may cease from sinning and live for righteousness. By his wounds you were healed.” Amazingly, such wounds are sacred and life-affirming because they give new life to those who draw from them, symbolized by the water flowing from Christ’s side; indeed, they become an agency of salvation. This is a redemptive mystery inviting us to reflect on how glory emerges from pain and suffering, a theme rehearsed several times in St. John’s gospel. As Varden astutely comments in his book Healing Wounds, “the exchange, his wounding for our healing, goes beyond the grasp of reason.”

The Catholic Tradition

The Stigmata

Elements in the Catholic tradition reflect this biblical teaching. For instance, although Saint Francis of Assisi is best known for his nature mysticism, he is also remembered because he received the stigmata, the replication of the five wounds of Christ on his own body; he was the first saint ever to receive these wounds. The historian Carlos Eire has noted how the sheer visible physicality of this occurrence was said to be a new marker in the history of the miraculous and salvific.

A more recent figure, Padre Pio (1887–1968) also had the stigmata imprinted on his body and was canonised by Pope John Paul II in 2002. But, as Eire writes, “Padre Pio was controversial in his day and continues to be as much a target of vituperation in the secular sphere as he is a magnet for veneration among some of the faithful.” What is also noteworthy is that some who experienced the stigmata, like Saint Catherine of Siena, the wounds were never visible, simply felt by the receiver.

Devotion to the Sacred Heart

Devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus in the Catholic tradition emanates from John 7:37-39 and John 19:33-37, the narratives of the Holy Spirit flowing from Christ’s wounded side. During the Middle Ages, a transition was seen from the wound in Christ’s side as a source of grace to the heart of Jesus as it became the focus of a more personal devotion. The feast of the Sacred Heart is always celebrated on the Friday 19 days after Pentecost. Pope Pius XII described the rich theological foundations of the devotion in his encyclical Haurietis Aquas (1956).

Henri Nouwen’s Examination of the Wounded Healer

In his most famous book, The Wounded Healer, Henri Nouwen refers to a legend in the Talmud. Rabbi Yoshua ben Levi comes upon Elijah and asks him, “When will the Messiah come?” Elijah replies, “Go and ask him yourself. He is sitting at the gates of the city. You shall know him as the one sitting among the poor covered with wounds. The others unbind all their wounds at the same time and bind them up again. But the Messiah unbinds one at a time and binds it up again, saying to himself, ‘Perhaps I shall be needed; if so I must always be ready so as not to delay for a moment.’”

Nouwen suggests here the readiness required of the teacher as wounded healer who must look after her own wounds and, at the same time, be ready and prepared to heal the wounds of others. She is at once the self-reflective person who knows her personal wounds and the alert, healing confidante ready to bandage the wounds of others when called for. Nouwen writes, “The Talmud story suggests that because he binds his own wounds one at a time, the Messiah would not have to take time to prepare himself if asked to help someone else.” Like Jesus, who makes his own broken body the ready agency of salvation, so, too, is the teacher encouraged not only to be cognizant of her own wounds and the wounds of others but also how she might turn them into a major source of healing power.

Nevertheless, it is easy to misuse the concept of the wounded healer and for it to become nothing more than “spiritual exhibitionism.” A teacher who consistently talks about her own problems only adds to the problem under discussion: “Open wounds stink and do not heal,” warns Nouwen. Making one’s own wounds a source of healing never calls for a misplaced sharing of personal pain, but for a constant willingness to see one’s own suffering as rising from the depth of the human condition which everyone shares. It is in the recognition of one’ s own injuries that she can become “a healing touch” for others, which makes it possible to convert weakness into strength.

Michael Ford writes that Nouwen “compares the wound of loneliness to the Grand Canyon—‘a deep incision in the surface of our existence which has become an inexhaustible source of beauty and understanding.’” Nouwen adds that whenever a teacher or minister “tries to enter into a dislocated world, relate to a convulsive generation, or speak to a dying man, his service will not be perceived as authentic unless it comes from a heart wounded by the suffering about which he speaks.” He also suggests that no authentic teacher “can keep his own experience hidden from those he wishes to help. But spiritual showing off is not the way forward. Remarks in the pulpit or classroom like ‘Don’t worry because I suffer from the same depression, confusion and anxiety’ help no one.”

In The Wounded Healer, Nouwen uses the concepts of hospitality and concentration and hospitality and community to explain further his understanding of healing. Hospitality is the ability to pay attention to the guest. This is difficult, since we are often wrapped up in our own needs, worries, and tensions which prevent us from helping and healing others. Concentration allied to meditation and contemplation is a necessary precondition for real hospitality. When we are restless, we allow ourselves to be driven by thousands of different thoughts and feelings. But, paradoxically, by withdrawing from the world in humble contemplation, we create the space for another to be herself. This is difficult to achieve, but without this kind of hospitality we cannot heal others.

Hospitality also establishes community because it creates a bond based on a shared confession of brokenness and hope: “Mutual confession becomes a mutual deepening of hope, and sharing weakness becomes a reminder to one and all of the coming strength.” Writ large, any Christian community has the potential to become a healing community, not because wounds are cured and pains necessarily alleviated, but because openings or occasions for a new vision are forthcoming from the positive experience of woundedness.

Eric Varden’s Exposition of the Wounded Healer

The late Pope Francis appointed Eric Varden bishop of Trondheim in Norway in 2019 when he was then Abbot of Saint Bernard’s Abbey in Leicestershire. Varden is a Cistercian monk. Before he entered the order, he had spent 10 years at Cambridge University. His latest book, Healing Wounds, is subtitled The 2025 Lent Book. It is an inspiring read.

In his book, Varden asks an important question: “By what means may I understand and experience Christ’s wounds not just in juridical terms, as the providential means by which God chose to ‘take away’ sin, but as the living source of a remedy by which . . . humanity’s wounds, my wounds, are healed?” He answers this by arguing that Good Friday’s commemoration of the passion, a service unlike any other in the church’s liturgical year, dramatizes the conquering of evil through the cross. In an age in which we witness the presence of evil on a daily basis, this is indeed a message which resonates with hope and the belief that evil will not have the final word.

Varden writes that during the liturgy worshippers “profess the faith that the death-tree of human design has become a tree of life.” He continues, “There is glory there but not of a kind that overwhelms and terrifies. . . . Since God presents Himself to us wounded, we dare to come before him with our wounds.” During the service, worshippers come before the cross to kiss the wounded feet of Christ. The priest goes first, not as a sign of superiority but as one who carries vicariously all that which the people of God carry. The rubrics prescribe that he should first remove his shoes, like Moses before the burning bush, since he is approaching holy ground. He is to be sensually conscious of his feet as he prostrates himself before the immobile but clearly wounded feet of his Savior. Varden admits that “Each year I am conscious of this sight as a display of humanity owning the truth about itself, peacefully acknowledging the suffering by which no life is untouched yet holding its head high in trustful hope, in the certainty of being, remarkably, loved.”

When the Easter season arrives, we hear of Christ appearing to Mary Magdalene in a garden. Varden advocates that there he awaits us all. His wounds remain, but they are glorified and the message of the wounded-and-victorious One is “Peace.”

Conclusion: Sharing Our Woundedness

One would be mistaken if one took from this article the view that teachers ought to be skilled psychotherapists by owning and transforming their own wounds for the good and healing of others. Certainly, as Farber comments, Carl Jung believed that we all have a collective unconscious in which exists the archetype of the wounded healer whose wounds are both a burden and a driving force in an individual’s need to heal the problems of others. However, what I have attempted to put forward for consideration is the more theological view: that by aligning our own wounds with the wounds of Christ and sharing in his redemptive suffering, we will be given the strength and know-how to heal others’ wounds, constantly assisted by his grace. We are not alone in our endeavors to heal. So, yes, I do think the paradigm of the wounded healer can assist those teaching and working in Catholic education at the present time. ♦

Dr. David Torevell is Honorary Senior Research Fellow at Liverpool Hope University, UK, and Visiting Professor at Mary Immaculate College, University of Limerick, Ireland. His latest book with Routledge, shared with Brandon Schneeberger and Luke Taylor SJ, is Exploring Catholic Faith in Shakespearean Drama: Towards a Philosophy of Education (2025). His monograph published in 2024 was entitled Desire and Mental Health in Christianity and the Arts and before that he edited with Clive Palmer and Paul Rowan Training the Body: Perspectives from Religion, Physical Culture and Sport (2022) He is presently working on a book about trauma in theology and literature. A version of this essay was published earlier this month in the journal Networking.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!