Lifeways: A Review by J. Milburn Thompson

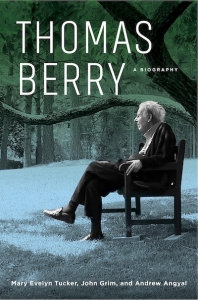

Thomas Berry: A Biography

By Mary Evelyn Tucker, John Grim, and Andrew Angyal

Columbia University Press, 2019

$28.95 339 pp.

Many people who have encountered Thomas Berry (1914–2009) through the classroom, a presentation, or his writings have been deeply changed, including me. In an age of specialization Berry was a renaissance person and a visionary. He was a Passionist priest whose early education in Catholic schools and the monastery steeped him in the classics of Western philosophy and theology. Then he explored cultural history, first the religious traditions that so profoundly influenced Chinese, Japanese, and Indian civilizations, then the traditions of indigenous peoples, and finally the scientific tradition of the modern Western world. He came to realize that all cultures are embedded not only in human history, but also in the history of Earth and the story of the universe (cosmology). Out of this breadth and depth of learning, Berry fashioned a vision that might offer humanity the wisdom to respond to the suffering posed by our destruction of the life systems of our planet and create a future where the community of life can flourish.

This clearly written biography is an excellent introduction to Berry’s life and thought. The first eight chapters present a chronological unfolding of his life. The final four chapters expound on key elements of his thought. The book includes endnotes, a helpful timeline of Berry’s life, a bibliography of books and articles by and about Berry, and an index. Mary Evelyn Tucker and John Grim, a married couple, worked with Berry for over 30 years as his students, editors of his books of essays, and collaborators. They both teach at Yale University, direct the Yale Forum on Religion and Ecology, and are managing trustees of the Thomas Berry Foundation. No one knows Berry better. Andrew Angyal is Professor Emeritus of English and Environmental Studies at Elon University. He visited with Berry nearly every week in the final decade of his life. This is his fourth biography, including one on environmentalist Wendell Berry from 1995.

Thomas Berry often called on everyone to contribute to today’s “Great Work,” that is, to create a flourishing future for the community of life. Let us consider some of his myriad contributions to the Great Work.

Berry became the first member of the Passionist order to teach at an institution other than one of their monasteries. He taught at Institutes for Asian Studies at Seton Hall University from 1957 to 1961, and at St. John’s University from 1961 to 1965. Then he accepted an invitation to join Fordham University’s theology department (1966–1979) and founded the History of Religions program there. This was the only program at any Catholic university in North America that emphasized the historical study of the religious traditions and their significance today, rather than a comparative approach.

Berry excelled as an interpreter and teacher of Asian thought and religious traditions. He published Buddhism in 1966, Five Oriental Philosophies in 1968, and Religions of India in 1971. (There are seven other edited books of his essays related to topics below.) For the next quarter century, in tune with Vatican II’s opening toward the wisdom and truth found in other religious traditions, Berry promoted the understanding of and dialogue among the world’s religions and the necessity of scholarship in Asian Studies for the church’s missionary work.

Berry was profoundly influenced by the Confucian tradition and by the mutual interaction of the three syncretic traditions of Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism. Along with his friends Ted de Bary, professor of Asian Studies at Columbia, and Tu Weiming of Harvard and Beijing Universities, Berry has been associated with the “New Confucians” who are reviving the tradition through new translations of the Asian classics, researching the development and spread of Confucianism, and articulating its relevance for today. Confucianism sees nature as interrelated and interdependent, a view compatible with evolutionary biology and ecology. Each part of the natural world is inherently but not equally valuable, a concept known as differentiation. Harmony with nature is essential for human self-realization and flourishing.

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, a Jesuit paleontologist and philosopher who reconciled evolution and faith, was a major influence on Berry, and Berry was a key proponent, interpreter, and critic of Teilhard. In 1967, Berry and other devotees established the American Teilhard Association for the Future of Man, which was eventually housed at Berry’s Riverdale Center for Religious Research, where he lived and worked. Berry served as the president of the Teilhard Association from 1975 until 1987, when John Grim succeeded him. Although Berry ultimately rejected Teilhard’s faith in progress, the two agreed that matter and spirit are differentiated, yet intertwined, aspects of reality. There is an interiority (Teilhard) or subjectivity (Berry) to evolution. “The universe is a communion of subjects, not a collection of objects” (p. 258).

Berry was also instrumental in creating a new academic field of study—religion and ecology. He repeatedly argued for a more constructive theological balance between redemption and creation. Although aware that religion is too often counterproductive regarding creation, Berry argued that the world’s religions can offer energy, symbols, moral persuasion, and motivation regarding ecological concerns and toward a flourishing future. A series of conferences held at Harvard from 1996 to 1998, organized by Tucker and Grim, resulted in 10 edited volumes on various world religions and ecology and evolved into the Forum on Religion and Ecology. Courses and programs on religion and ecology now exist at several universities. There are widespread conferences and lectures, and two journals in the field.

Berry observed that genuine transformation often comes from the margins of dominant societies. Thus he contends that indigenous peoples can teach dominant societies how to shape a future in which Earth is not regarded simply as a resource, but as a source of life itself. Blinded by the ideology of Manifest Destiny, European immigrants did not allow native peoples to teach them anything. Indigenous lifeways that recognize humanity’s kinship and reciprocity with the community of life are indispensable for reestablishing a relationship with Earth processes and a flourishing future.

Berry’s encounter with indigenous traditions and study of ecology itself led him to propose a philosophy and principles for “Earth Jurisprudence.” He found the contemporary legal system ill-equipped to respond realistically to questions about human-Earth relations. Nature has no legal standing. But if all the components of life are interdependent, and if nature and ecosystems have inherent value, then we need to recognize the rights of nature—the right to be, the right to a habitat or place to be, and the right to fulfill its role in the ecosystem—although all rights are limited and relative.

Berry proposed a new religio-scientific cosmology for our age in The Universe Story (with scientist Brain Swimme, 1992). His vision and thought offer humanity hope and guidance for a future in which the whole community of life can flourish. Thomas Berry: A Biography is essential reading.

J. Milburn Thompson is professor emeritus of theology at Bellarmine University, in Louisville, Kentucky. He took three courses with Thomas Berry in his graduate work at Fordham University. The Third Edition (Revised and Expanded) of his book Justice and Peace was published by Orbis Books in June.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!