Songs of the Hours By Fr. Bob Bonnot

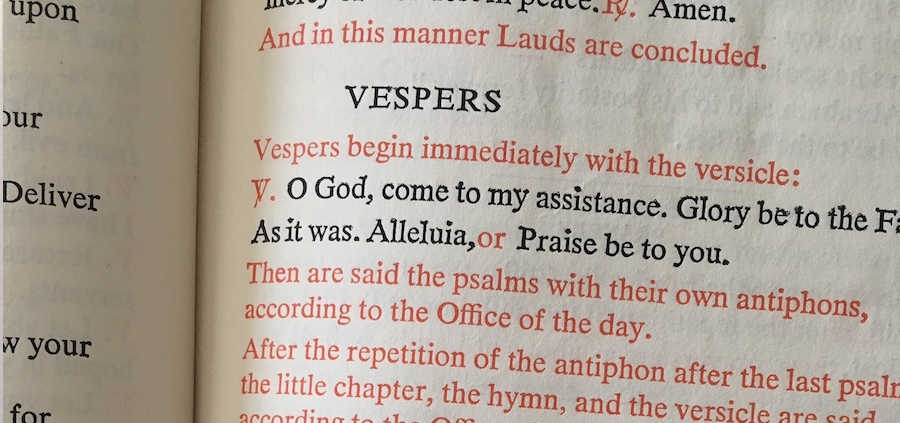

The Liturgy of the Hours, sometimes referred to as the Divine Office, is a series of prayers, psalms, hymns, and scriptural readings prayed at appointed times throughout the day by members of the church all over the world. There is a total of seven appointed prayer times in the Office, including Lauds (morning), Terce (midmorning), Sext (noon), None (afternoon), Vespers (evening), Compline (night), and Vigils, or the Office of Readings, which can be prayed at various points throughout the day.

Lauds, Vespers, and Compline each include a canticle from the Gospel of Luke: the Canticle of Zechariah from Luke 1:68–79 for Lauds (known as the Benedictus), the Canticle of Mary from Luke 1:46–55 for Vespers (known as the Magnificat), and the song of the Elder Simeon from Luke 2:29–32 for Compline (known as the Nunc Dimittis). In the essay below, Fr. Bob Bonnot reflects on the church’s daily use of these three Lucan canticles. In this Year of Luke, his insights particularly timely, and the invocation of the canticles throughout the day might add a new dimension to one’s prayer experience—Ed.

The Benedictus and the Baptist: Our Baptism and Our Mission

The Benedictus Song of Zechariah is part of the church’s morning prayer. I find that choice ever more appropriate. It’s there every day, I think, so each of us baptized in Christ will understand that what Zechariah sang to his son John is what the church wants us to hear God sing to us each morning. Zechariah’s song is God’s Word.

The song starts proclaiming that God has come and raised up a savior for his people. His purpose is to set us free, to save us from our enemies and those who hate us. Us! For we are God’s people. With Zechariah we then remember God’s promise to show mercy in the covenant God swore to Abraham, our father in faith. It spells out the provisions of that covenant in a triplet: to free us from the hands of our enemies; to free us to worship God without fear; and to enable us to live holy and righteous lives before God, always. That’s salvation: to live without fear but rather with a focus on God that will make us holy and righteous.

Zechariah’s song is a wonderful summary of the nature of God, the work of God, and the point of our entering relationship with God through baptism into Christ. There is a lot to think about there, a lot to take to heart as we begin each day.

Only after that bracing and all-embracing meditation on God does Zechariah turn to the child whose birth loosed his tongue and enabled him once again to sing. “You, my child,” he says. Every time we pray this Benedictus, we each need to hear those words spoken to us. We know Zechariah’s son as “the Baptist.” We are to be mindful each day that we are “the baptized.” What Zechariah says to his son John, God speaks to us each and every morning: our mission for each day, our deep purpose, God’s reason for our being and doing. Here is our charge: to be a prophet of the Most High; to go before the Lord, preparing his way; to give people knowledge of salvation; and to assure people that their sins are forgiven, that God is merciful.

Having sung to his son, Zechariah sings again to God. He sings of God’s tender compassion and sees it as the sun of mercy breaking upon us like the dawn, shining once again on those who dwell in darkness and the shadow of death.

That’s what we the baptized need to be about every day. That’s our mission. We are sent forth each morning to reach out to those in darkness, to share the deifying light that comes to us in Christ, thereby guiding peoples’ too often fear-filled feet—ours and others—to peace.

Mary’s Magnificat: God Is Great . . . And So Are We!

One of the best known and most perplexing “shout-outs” of our time is the Arabic acclamation Allahu akbar!, “God is great!” We hear it too often as a blood-curdling cry because we have encountered it mostly on television from the mouths of radical jihadists. How different would it sound were we to hear it coming from the mouth of a young Jewish girl from Nazareth?

We should hear it this way. For that is exactly what came out of Mary’s mouth when she, freshly pregnant, visited her cousin Elizabeth to help with her pregnancy. That is what the church has us sing every evening as we pray Vespers.

The greatness of God is a sense and a sentiment we Christians share with Muslims and Jews. Mary’s Magnificat is our best known and most used way of proclaiming that truth. Perhaps our familiarity with her 9-verse, 125-word song causes us to miss its simple message: “God is great . . . and makes us great.”

Mary sang in response to Elizabeth’s telling her that she was “most blessed among women”—holy, special, great—for two reasons. First, she believed the Word spoken to her. Second, the Lord fulfilled the promise that Word contained: she became pregnant.

Mary, it seems, deflects Elizabeth’s greeting by immediately responding that she is aware of how great her Lord is. Then she spells out what she means. She describes herself as a lowly servant. She rejoices in God’s special favor shown her. She acknowledges that she will be called blessed forever forward, not because of herself but because “the Almighty has done great things for [her].” Yahweh is the great and holy One. Then she spells out qualities that constitute her Lord’s greatness: mercy, strength, concern for the poor, generosity, readiness to help, keeping promises. God is the great one, not she.

Yet she too is great, for the Great One has brought all that greatness to bear on her. She is one of the lowly and hungry servants who live with a sense of joyous awe before their Lord and savior. Mary clearly understands that the greatness shared with her makes her responsible to proclaim God’s greatness and to enflesh it by “going and doing likewise.” No sooner does the angel who greeted her as “full of grace” depart than Mary herself departs to be grace for Elizabeth “in her sixth month.” She goes to share her mercy, her strength, and her ability to lift, bathe, feed, and clean. We remember her for all of that, not just for saying “yes” and giving birth to a special child. All her life she helped make Jesus great. Then she travelled with those who accompanied him in his great work among us, to the end.

When we pray the Magnificat each evening, we in effect shout out Allahu akbar! The two words capture it all. When we are weary or our memory falters, those few words in English are surely enough: God is great! When Jesus was asked to teach his disciples how to pray, he told them not to multiply words. He taught them a simple prayer for each day, a mere 38 words in Luke’s version.

When pressed for time at the end of each day’s pilgrimage—our spiritual jihad, our struggle, our intense effort to allow God to make us holy and “great”—perhaps it’s enough just to proclaim with Mary God is great!—and to remember that God makes us great too.

Simeon’s Canticle: Signing Off on God’s Daily Revelation

As night falls, the church’s prayer invites us to remember an event that probably happened in the morning: the prayer of Simeon in the evening of his life. He was a regular at the Temple and was ready to meet his maker, but he was waiting for something, a final fulfillment, a revelation.

Then it happened. A man and woman with a baby approached and he knew for certain that this was it. Simeon knew revelation. He had experienced it before. He was a devout and religious man, attuned to the Spirit. He was attentive to words he heard and promptings he felt. He knew how to discern what came from Yahweh and what not.

On that morning, moved by the Spirit, he came into the Temple expectant. Perhaps he did so daily, listening for the word, responsive to his feelings, hoping that he would receive some new revelation to live by . . . or die by. As it turned out on this day, it was a revelation he could die with.

He saw them approaching and he knew. He welcomed them with delight, took the baby in his arms, and prayed the prayer that Luke recorded in his Gospel and that the church includes in her night prayer:

Lord, now let your servant go in peace;

your word has been fulfilled:

my own eyes have seen the salvation

which you have prepared in the sight of every people:

a light to reveal you to the nations

and the glory of your people Israel.

Prior experiences left Simeon convinced that he would see the Messiah before he died. He was waiting, ready. Now he saw with his own eyes as had the shepherds and the Magi. In seeing the infant, he knew the time Yahweh had prepared for over centuries was beginning, the time of the Messiah. He knew it in his heart. That morning, he experienced salvation for all people. He was old enough to know well the darkness that comes over us. Here was light, a Light that would shine through Israel to all the nations.

At the end of each day, before darkness envelops us, the church invites us to reflect on the light we have seen and taken into our arms in the course of that day. It offers us a moment to remember the brief but surprising encounters we have had, the fulfillments we have experienced, the salvation embraced, and the good news we have shared with others.

In our culture the day’s mostly dark events are recounted in the evening news. That pattern shrouds our minds and hearts with darkness. Recalling Simeon’s encounter with that little family and praying his words can focus us anew on the light, lifting and comforting us even in the face of death. We can acknowledge the darkness as Simeon did with a few words to Mary and then dismiss it, as we give Yahweh permission to dismiss us, “now.” With Simeon, we will have heard and seen enough to go to sleep, even forever, in peace.

Bob (Bernard R.) Bonnot is a priest of the Diocese of Youngstown, now retired, serving as the Executive Director of the Association of U. S. Catholic Priests (AUSCP).

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!