From Child Star to Hospital Chaplain by Michael Ford

I love watching movies—detective mysteries, especially, but any film which tells a strong story with artistry and style. Sometimes it’s essential to watch these productions more than once to observe the subtleties of plot and dialogue. After an evening’s showing, I always try to find out as much about the making of the movie and those who have starred in it.

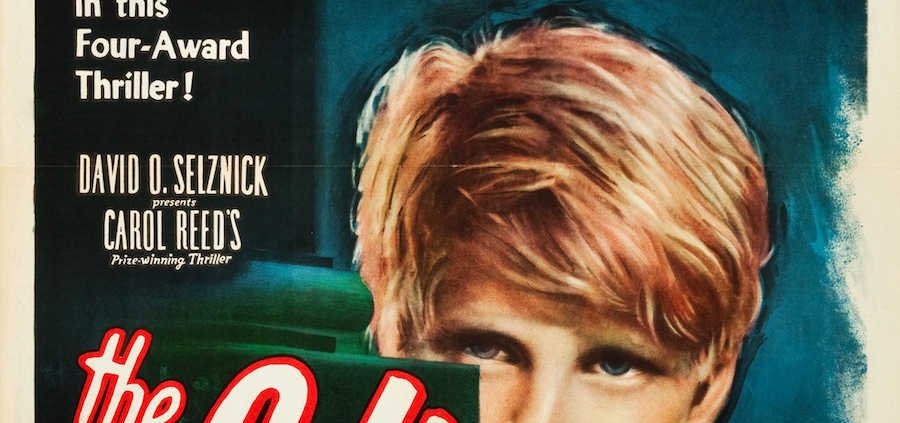

When I was working on my book Watershed about turning points on the spiritual road, I decided to feature a chapter on the illusion and reality of the cinema. I had already tracked down Jon Whiteley, a Scottish boy who had played opposite Dirk Bogarde in Hunted and had gone on to become an art historian. I wondered if I could locate another child star. A screening of Carol Reed’s The Fallen Idol provided the opportunity. It’s a gripping and tragic tale about an ambassador’s son called Philippe who idolizes his butler, Baines. I noted that the eight-year-old, blond-haired boy with a slight French accent was billed as “Bobby Henrey.”

I didn’t recognise the name and subsequent research revealed that here was another young actor who hadn’t remained in the industry. I couldn’t help but wonder what had become of him, so on went my journalistic hat and eventually I discovered that Bobby Henrey was now the Reverend Robert Henrey, a married deacon in the Roman Catholic Church. I managed to trace Robert to a town in Connecticut where he was about to retire as a chaplain at Greenwich Hospital. As you can imagine, he was a little surprised to hear from me.

Through correspondence, Robert told me how he had been born in a quaint medieval farmhouse in Normandy (which he still visited) but moved with his near penniless parents to London in the early years of the war. His father, a journalist, had gotten a government job penning war-related stories, but constantly broke, had decided to turn to writing. One of his books, A Village in Piccadilly, happened to include several photographs of his son. The book came into the hands of a member of a film crew adapting a Graham Greene short story, “The Basement Room,” for the big screen with Ralph Richardson, Michèle Morgan, Jack Hawkins, and Sonia Dresdel. Producers were on the lookout for a juvenile lead and thought Bobby could be perfect for the role.

“They sent a private plane to nearby Deauville airport to pick me up,” Robert recalled. “The only thing I remember was the thrill of flying for the first time—the views from the little plane as it banked over the Normandy fields and headed north over the English Channel, the din of the engines and the smell of the petrol. What did I know or care about filmmaking! I do remember a meeting in a swank office around Marble Arch overlooking Hyde Park. I assume that both Alexander Korda, the owner of London Films, and Carol Reed were there but I must have been far more interested in the strangeness of the setting—the wood panelling and the high ceilings—to give much thought to the names of those who were talking to me. Anyway, after that, my mother told me we would be spending a lot more time in London and that it had something to do with this film business.”

Robert lived with his mother in a residential suite that formed part of the studio facilities. He also had a governess. He remembered Carol Reed as a fine director who had probably needed a great deal of patience in dealing with the boy’s inquisitive nature. Rather than constraining the young Bobby to do things the director’s way, Reed would observe him, then encourage him to act in accordance with his own innate mannerisms. Despite Bobby’s endearing performance, his movie career lasted a mere eight months, after which he was sent to a Benedictine boarding school where he had to fend for himself among children his own age. The transition was far from pleasant. He coped by putting the film experience to one side and pretending to himself that it had never occurred. After the bright lights of the studio set, returning to live a normal life proved far from easy and he felt different, his celebrity status as a talked-about child actor contributing to his feelings of isolation.

Although fame didn’t go to his head, he couldn’t help being aware of his special status. People would stop him in the street and gawk, and there were endless interviews and pictures. While his parents, especially his mother, enjoyed all this, Robert was more bemused than anything else, “but we humans are naturally quite vain.” Robert went on: “Some of this must have percolated through into my psyche. As an adult I would describe myself as a rather private person who is not good at schmoozing and who dislikes being schmoozed. Fame—like the illusion of power—is a potent brew with complex side effects.

“Early on I got the message that the stage is in some ways more real than reality, and that story, metaphor, and ritual are enormously important to our understanding of life: an essential lens through which to sharpen our understanding. I think this is what good religious practice and ritual are all about. Ministry in a religious context is associated with taking on a part.

“I’d like to think that when all is said and done it taught me humility: this is something that happened to me to a large extent by chance. It was actually a good thing and it was important to do it to the best of my ability, but it was a gift—gifts can be hugely complex and confusing things to deal with. Above all, they need to be accepted with humility, otherwise things can go seriously wrong.”

Much to the unease of his Protestant family, Robert later became a Roman Catholic. He says Gregorian chant attracted him to Catholicism while his Benedictine teachers helped him win a place to Oxford where he met his English wife, Lisette, and was also fortunate to have a tutor who taught him to relish reading and encouraged him to discover different languages. Far from the realm of moviemaking, Robert entered the world of chartered accountancy, living in Asia, Latin America, and the United States. He became a partner in one of the large accounting firms in New York and was involved in corporate tax work.

Robert told me that he had long been aware of his contemplative nature and, had he not married young, might have been drawn towards a monastic vocation. When he was 40, Robert moved back to New York after living in Singapore. The couple had two young children and knew it was time to settle down. Although committed to an extremely demanding career, he wanted to set limits. He knew that, since the Second Vatican Council, the Roman Catholic Church had been willing to ordain married men as deacons, so he decided to offer himself. The formation involved three years of part-time theological study and a willingness to make a lifelong commitment. Ordained in 1984, Robert was assigned to his local parish in Connecticut, but also found himself gravitating towards hospital ministry.

“It was part-time, obviously, since I was taking the train into Manhattan every weekday to earn a living,” he said. “It was a good experience from the beginning—none of my partners ever objected to my having committed myself to doing something outside the firm. When I retired at the relatively young age of 58, I still had enough energy to move into a second career. Over two years I embarked on a series of clinical internships in hospitals leading to a certification as a chaplain. That enabled me to get a professional job with a hospital, ministering not just to Catholics but to all patients. The training was challenging and enriching with an emphasis on psychology, mental health, and working with all religious traditions.”

Robert and Lisette had two children, Dominique and Edward, but, shortly before her 19th birthday, Dominique (a talented young woman who would have become a professional writer) died from an allergic reaction while in her first year at Columbia University. “We knew she had a serious allergy to peanuts,” Robert told me. We were on vacation at Christmas and she died from anaphylactic shock after drinking a cup of chocolate—it must have contained traces of peanut. This happened in 1988 and had a profound impact on my life, my wife’s and my son’s—we were all together when it happened. It was devastating. Edward was 15 at the time.

“One of life’s lessons is that intense pain takes each of us on a highly personal journey—we’re alone with it and have to muddle through in the hope that the sunshine will one day make its way back into our lives. It’s the loneliness of it that makes us so vulnerable to giving up on our relationships. My wife and I were spared that—we made it through together. When eventually I did make it through recovery, the fact that I was a deacon helped me listen to the pain of others . . . and that was a privilege. None of us wants to experience pain—that kind of pain should be avoided at all cost. But the reality is that pain, however unwelcome, is a powerful teacher.”

Michael Ford is an author and theologian in England, where he worked in BBC news and religious broadcasting for many years. His articles for TAC reflect spiritually on his life as a journalist and writer.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!