Sanctity in a Secular Society by Gene Ciarlo

“Holiness is as universal as sin,” says Gregory Baum in Man Becoming: God in Secular Experience. At the time this book was written in 1970, Father Baum was professor of theology at the University of St. Michael’s College at the University of Toronto. The thoughts that he expressed in his work were groundbreaking at the time: that everybody is open to God’s grace and grace is available to everyone, whether you are Catholic, Muslim, Jew, just plain Christian, Evangelical, or profess no religion at all.

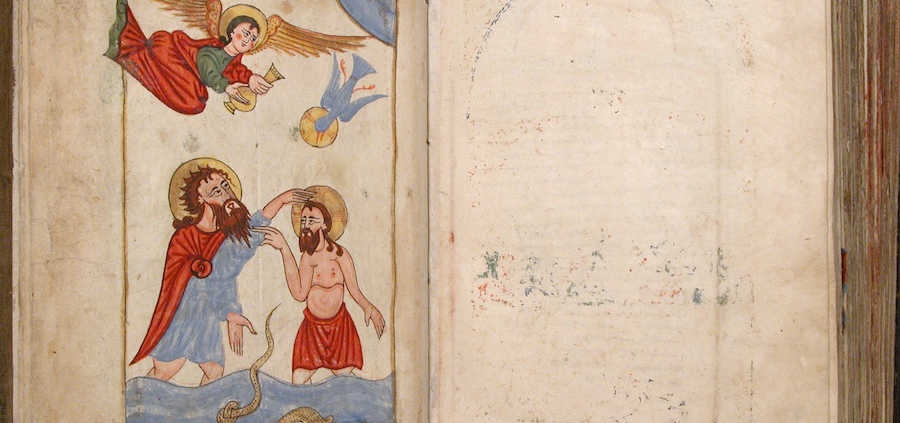

The idea defies the Catholic Church’s traditional theology that you need at least a baptism of desire in order to receive the grace of God for salvation’s sake. It takes the scriptural words of the Gospel of John 3:5 quite literally: “Jesus answered, ‘No one can enter the kingdom of God unless he is born of water and the Spirit.’” From that literalness, “water and the Spirit,” the Catholic Church conceded a bit and said that baptism of desire would be enough to gain salvation. Does that mean that it is enough to simply to want to be a “God person”? Is that kind of desire enough to warrant salvation?

The floodgates to various interpretations of John 3:5 opened up when Martin Luther said that good works are necessary but faith alone gives life. In today’s world, with biblical exegesis highly developed and the advent of formgeschichte—defined as the effort to discover the original form and historical context of scriptural words and ideas—we can no longer take scripture literally and out of context. If we were literalists, we would find that the Bible contains a multitude of falsehoods, disproved by science and given the lie simply due to time and the development of our intellects, our knowledge and awareness.

There are lots of holy people, men and women of compassion, love, awareness, mindfulness, and other great virtues abundant in the human spirit who know nothing of God and don’t belong to any religion. With that understanding, the big question arises: What is the advantage of owning and confessing a religion? Is it just to add to the burden that life already places on us? Why bother?

This reminds me of another title of a book, Good Without God by the humanist Greg Epstein. Epstein does not talk about the advantage of belonging to and owning up to active participation in a religious body of believers in Jesus, in God and the Spirit. What is the advantage of owning a religious belief and practice, he contends, if you can be good, Spirit-filled, and holy without God?

In a word, it is easier to be good with God with a knowledge and practice of religion. The destination is always easier with a path to follow, even if it be the road less traveled. As with anything that helps us to make life livable—and not only livable, but graceful, fruitful, fulfilling, and productive—we need to find a way to integrate it into our daily practice. For a Catholic this implies that a person do much more than simply go through the motions of religion. That avails one of nothing and is, in fact, precisely the waste of time and effort in religion.

That is why it is of the utmost importance not to simply follow laws and rules. Finding the right environment to become eminently human, and therefore reaching our highest potential, is what a religion in belief and practice is all about. Being part of a community of faith can transform a person’s life. I think of the Tin Man in the Wizard of Oz. He was looking for a heart. He found it, but only in the company of beings who were also on a search. He was in the right environment to find a heart and so he did. Desire, knowing what you want to accomplish and going after it, are essential for the Catholic as well. If it is a matter of fidelity to doctrines, obeying the laws and rules that the church has laid down over the centuries, then we are just adding an unnecessary burden to our already overloaded lives and we are wasting precious time.

G. K. Chesterton, the 19th-century English critic and author, put it succinctly in his book What’s Wrong with the World?, the subject of which is quite appropriate for our time. In it he coined the now commonly tossed-about cliché, “The Christian ideal has not been tried and found wanting. It has been found difficult and left untried.”

Has the Christian ideal been left untried? Perhaps so. What too many Christians have tried over the years is to live by “the Book,” by what they think the Book says, and to follow the norms, the rules, the customs, the doctrines and dogmas that representatives of the Book have put forth. This means to live by a book that is largely misunderstood and misinterpreted rather than to live by the message, life, and example of the God-Man, Jesus. To do that is much tougher than just being obedient to the prescriptions of the laws laid down by various Christian churches over the centuries for the sake of orthodoxy and to retain foundational principles. All of that was sociologically essential at one time, for uniformity of practice and all the other externals that our human condition demands when we are dealing with large numbers of people. With that understanding, shall we ask again: Has Christianity really been tried?

We are living in a secular age. It is much more difficult today to really live a Christian life because it is an uphill battle challenging the duplicitous, negative, and superficial forces of our society. The 21st century is not living the principles that we understand to be in the spirit of the Christ. This age was anticipated by theologians decades ago who proposed what was then called secular theology. Writers like Paul Tillich and Bishop John Robinson were condemned at that time for their heresy. How could they preach and teach a “secular theology” which allowed the denial of many dogmas and teachings of ancient Christianity? Was it really a denial or a bringing up to date, a revisionist theology that allowed for hell and damnation, heaven and angels with a new kind of fire and new wings?

Gregory Baum puts this new understanding in just three little words: “Grace is secular.” Grace is of the world in which we live, move, and have our being, which is where Jesus lived. To carry this theme yet further, there are secular priests among us. Those are the men and women who are, in fact, living the Christian life. Without naming names, I have come across a few in reading, disputably, the most secular of secular newspapers, the New York Times, including a writer whom I would identity to be a priest for the secular age. His mindfulness, depth, and spiritual life are tangible in his thinking and writing. This is a person who is living what Christianity is supposed to be all about. As Chesterton said, it has been found difficult, yet some people have tried it and they are glorious to behold. They are the saints in modern dress, never to be canonized, and they don’t have to profess any religion or wear it on their sleeves. They have it in their hearts and live it in their daily lives—not an easy feat in our day and age.

It becomes easier to believe that such people exist when you realize that Jesus never intended to start a religion. He was the original secular priest for his time, even though they tried to ordain him by calling him “Rabbi.” He didn’t know what Christianity was. Perhaps at some times, and in some places, he still doesn’t recognize it.

Gene Ciarlo is an ordained Catholic priest no longer in the active ministry. He lives and works in Vermont. He has been writing for Today’s American Catholic since the early days of its publication.

I always enjoy reading Gene’s column. He writes beautifully and thoughtfully, and with such a creative and open spirit. I love watching his pure intelligence, and open heart, express itself in his writing. I am not a Christian, and certainly not a theologian, but Gene’s open-minded thinking and sensibility exemplifies, in my view, what it means to be the kind of secular priest he writes about.