A Glorious Presence Out of Place in the World: On Marilynne Robinson by Leonard Engel

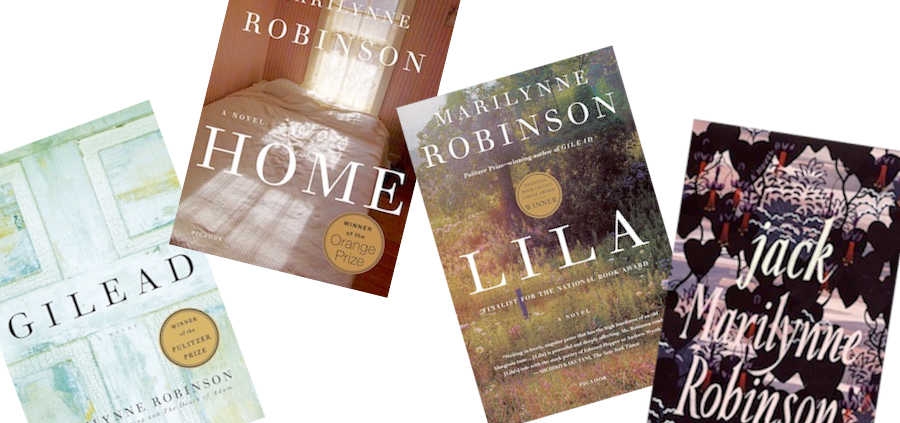

Marilynne Robinson’s breakout novel Housekeeping (1980) won the PEN/Hemingway first novel award and was a finalist for a Pulitzer Prize for Fiction and the National Book Award. She then wrote four books of nonfiction, most notably Mother Country (1989), about nuclear waste and its cover-up in Britain (the book was banned in the UK), and The Death of Adam (1998), a collection of essays which criticized the vacuity of American life. Twenty-four years after Housekeeping came another novel, Gilead (2004), which won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, followed by Home (2008), Lila (2014), and Jack (2020).

In Gilead, Reverend John Ames, a 67-year-old minister of the Congregational Church in fictional Gilead, Iowa, in the 1950s, has been a widower for the past 30-plus years. Two years before the novel begins, he has married again and has received a dire medical diagnosis; the book itself is in the form of a letter he writes to his infant son. Home focuses on the family of Reverend Robert Boughton, minister of the Presbyterian Church in Gilead and close friend of Ames. A widower in ill health, he has eight children. His youngest daughter, 38-year-old Glory, has returned home to care for him. Lila, set a few years before Gilead and the strangest of the three novels, tells the story of a woman, unknown to the community, who appears one day in the back of John Ames’s church while he is preaching. He falls almost instantly in love with her. He is nearly twice her age and couldn’t be more different in background, education, and interests, but Robinson makes clear the one thing they have in common: loneliness. They marry and have a son, Robbie, to whom Ames is writing in Gilead.

A character named Jack Boughton, one of Reverend Boughton’s eight children, makes brief appearances in all three novels. He is frequently talked about as having caused concern, grief, and intense anger among members of the community, including his family members and Reverend Ames. He is presented as a troublesome character: suddenly disappearing in the midst of family gatherings; refusing to attend church in his youth; stealing, drinking, taking drugs, and having run-ins with the police; and ultimately fleeing Gilead after impregnating a 15-year-old girl, returning only intermittently. Prior to publication of Jack in 2020, Robinson had been asked in interviews if she might devote a whole novel to him since he is such a disruptive yet compelling character. Her response then was: “I would lose Jack if I tried to get too close to him as a narrator. He’s alienated in a complicated way. Other people don’t find him comprehensible and he doesn’t find them comprehensible.” Apparently she couldn’t resist his attraction, and her focus on Jack in this latest addition to the series still leaves abundant room for yet another novel if she decides to continue writing about these two families.

It is important to note the structure in each of the four books: Gilead is in first person (Ames’s letter to his son); Home and Lila are in the third person; and Jack is in third person with extended dialogue between Jack and the people he encounters. What distinguishes Jack from the earlier novels is Robinson’s insertion of Jack’s freewheeling thoughts after almost every line of dialogue, so the reader apprehends not only Jack’s outer self, his appearance, through his comments to others, but his inner self—his thoughts as he is making these comments, which often conflict with what he says. This is not unlike the structure in some of William Faulkner’s novels, notably the Quentin section of The Sound and the Fury.

Unlike the earlier three books, Jack is not set in Gilead, but mostly in St. Louis, and it may have the oddest beginning in any work of contemporary fiction. After serving a two-year sentence for a crime he didn’t commit, Jack has just been released from prison, and in the middle of a rainstorm he sees a woman struggling to hold a stack of papers that are falling onto the pavement. He runs to her assistance, offers an umbrella, and picks up the papers. He then walks her to her apartment in the Black neighborhood of the city, and she invites him in for tea. The time is mid-1940s, when Missouri still had a strict miscegenation law and violators, especially Black women, were often beaten by white supremacists if they were even seen with white men. The woman, Della Miles, is from a well-respected Black family in Memphis and is teaching in a highly esteemed Black high school is St. Louis. She is also fully aware of the existing Jim Crow laws. However, something about Jack attracts her, and he is smitten by her beauty and intelligence. They start an uneasy relationship, and one evening while eating in a safe restaurant, he abruptly gets up without explanation and says that he’ll be back in a few minutes. Instead he disappears, leaving her with the check and a lot of embarrassment. Then one evening, not long after, he follows her home. Here is Robinson’s rendition of the scene, which gives a feel for the novel’s naturalistic speech:

He was walking along almost beside her, two steps behind. She did not look back. She said, “I’m not talking to you.”

“I completely understand.”

“If you did completely understand, you wouldn’t be following me.”

He said, “When a fellow takes a girl out to dinner, he has to see her home.”

“No, he doesn’t have to. Not if she tells him to go away and leave her alone.”

But he crossed the street and walked along beside her, across the street. When they were a block from where she lived, he came across the street again. He said, “I do want to apologize.”

“I don’t want to hear it. And don’t bother trying to explain.”

“Thank you. I mean I’d rather not try to explain. If that’s all right.”

“Nothing is all right. All right has no place in this conversation.” Still, her voice was soft.

She said, “I have never been so embarrassed. Never in my life.”

She shook her head. “Me scraping around in the bottom of my handbag trying to put together enough quarters and dimes to pay for those pork chops we didn’t eat. I left owing the man twenty cents. Well, here’s my door. You can leave now.”

He said, “I have a few minutes. If you want to talk this over in private.”

“Did you just invite yourself in? Well, there’s nothing to talk over. You go home, or wherever it is you go. I’m done with this, whatever it is. You’re just trouble.”

He nodded. “I’ve never denied it. Seldom denied it, anyway.”

Time passes, and one evening Jack again follows Della, this time into the white-only Bellefontaine Cemetery where they resume the conversation, sort of, for the next 74 pages. The setting is obviously tranquil, but both Della and Jack are filled with intense emotion. Robinson juxtaposes their dialogue against Jack’s inner, sometimes tortured, thoughts. He refers to himself as a “bum” who is no good for her. Della is still furious over his abandoning her in the restaurant. “All my life I’ve been a perfect Christian lady,” she says. “I actually am full of rage. Wrath.” Nevertheless, they continue to talk, then discover they’ve been locked inside the cemetery. Having no recourse but to continue walking among the graves and tombstones, they talk of many things: history, philosophy, religious faith, belief systems. Their conversation is filled with quotations from scripture, Milton, and Shakespeare (especially Hamlet—Jack, we learn, has had suicidal thoughts), in addition to modern poets. At one point, Jack refers to himself as the “prince of darkness.” “I am at the center of a certain turbulence,” he says, like “any bum dozing on a bench . . . steeped in beer and sunshine.” Frustrated, Della remarks, “I have never heard of a white man who got so little good out of being a white man.” It is a long night, to say the least.

When dawn approaches and a guard unlocks the gate, they leave separately to avoid suspicion but continue to see each other; their subsequent conversations are wide-ranging but never far from religion and belief. At one point Jack says, “I actually believe in predestination. I’m serious.” When Della responds that she doesn’t, Jack fires back, “Well, of course you don’t. Destiny has made you a Methodist. We are not as we appear.” Surprisingly, this “prince of darkness” promises to reform, makes positive changes, and even has minor success in the jobs that follow. Their love deepens, and Della testifies to it in an epiphanic moment:

Once in a lifetime, maybe, you look at a stranger and you see a soul, a glorious presence out of place in the world. And if you love God, every choice is made for you. There is no turning away. You’ve seen the mystery—you’ve seen what life is about. What it’s for. And a soul has no earthly qualities, no history among the things of this world, no guilt or injury or failure. No more than a flame would have. There is nothing to be said about it except that it is a holy human soul. And it is a miracle when you recognize it.

In the three earlier novels, Robinson immerses us in our country’s tragic history of slavery. In Jack, she highlights the evils of segregation and violence against Blacks during the Jim Crow period, and this becomes a major problem for Jack and Della as they plan their common-law marriage. Della’s family members are outraged and try to intervene; they are proud of their respectability and status. However, Della’s love for Jack is so great that she insists on inviting him home to meet them. Most want nothing to do with him. She is their rising star, and they know this lowlife white man could ruin her and bring the family down as well. Della tells Jack that her father, a bishop in the Methodist Church in Memphis, “doesn’t believe in marriage between the races,” then adds, ironically, “I probably don’t either.” On their first encounter, the bishop gives Jack “a look like a rifle shot,” and later, when they’re alone, tells Jack that if he persists in the relationship with his daughter, “You can never be welcome here.”

One reviewer has called Jack “a Calvinist romance . . . the love that arises between Della and Jack is more or less divinely ordained.” Another agrees: “Theirs is fated love, inexorable and mystical”; they “seem designed to enact the parable of redemptive love undermined by a fallen world; they are undone by America’s ‘original sin.’” Robinson herself has been identified as a Calvinist. She is an active member of a Congregational Church in Iowa City and often delivers sermons (one critic calls her a “gifted preacher”). She has also taught at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and has Professor Emerita status from the University of Iowa. It is known that in her writing classes she would often assign readings in Calvin, Johnathan Edwards, and John Winthrop, in addition to Poe, Hawthorne, Melville, and Faulkner, among others. Undoubtedly there are elements of predestination in her novels—actions determined by outside forces rather than individual will. But for the most part she presents her characters with choices they are forced to make and are then are held responsible for—although, in Jack, the line between choice and predeterminism sometimes blurs.

The conclusion of Jack is mystifying and ambiguous, but it also enlivens our curiosity about the continued travails of Della, Jack, and their son Robbie as they enter the initial stages of a more enlightened era—the 1960s. The reader hopes that Robinson will consider following their lives during the early days of the civil rights movement. In Jack’s final paragraph, Robinson bestows “grace” on Jack and Della, and I conclude with a passage from Valerie Sayers’s review in Commonweal that perfectly sums up of this fourth book in the Gilead series:

Robinson holds ideas and experience in a fine balance; she offers the possibility of love and forgiveness alongside the reality of bitterness and violence. But the ultimate satisfaction is the precision, wit, and intelligence of her glorious rhythmic prose. In Home, Jack’s sister Glory observes that “there was a kind of grace to anything Jack did with his whole attention.” In Jack, a reader senses Robinson’s whole attention, and responds in kind. Like Jack, like Della, this novel may be imperfect—but it is beautiful.

Leonard Engel, Professor Emeritus of English at Quinnipiac University, lives in Hamden, Connecticut, with his wife Moira McCloskey. He can be reached at Len.Engel@quinnipiac.edu.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!