Get Off of the Couch and Out of the Pew by Stephen B. Kass

In his article “Show Me Your Shoulders – The Stoic Workout,” Dr. Kevin Vost cites a quotation from the famous Greek Stoic philosopher Epictetus: “Suppose, for example, that in talking to an athlete, I said, ‘Show me your shoulders,’ and then he answered, ‘Look at my jumping weights.’ Go to, you and your jumping weights! What I want to see is the effect of the jumping weights.” The quotation appears in the Discourses (I, 4 [1]), which was written by one of Epictetus’s students early in the second century AD in an attempt to capture and record some of the great philosopher’s informal lectures.

In our modern culture, the term stoic is often used to connote a person who shows little emotion or passion, or who is restrained in their response to pain or distress. But this philosophical school, which was founded by the Cypriot Zeno of Citium and the Greek philosopher Heraclitus in the third century BC, is perhaps best characterized by its intense practicality. It is true that Stoic philosophers would downplay the importance of feeling and emotion in deference to the logic and order they believed were at the heart of the created universe. For the Stoics, philosophy was not abstract science or rhetoric; it was a way of life characterized by constant practice, training, and outcomes. The quotation from Epictetus gets to the essence of this notion by emphasizing that observing an athlete’s “jumping weights” are much less important than noting the results of using those weights. The well-developed shoulders of an athlete who uses “jumping weights” are what matter most to Epictetus, or any other Stoic.

Today, one could only wonder what kind of reaction Epictetus would have to the fact that the fitness industry in America is worth approximately $30 billion and growing by 3 to 4 percent each year. With that kind of spending, one would expect us to live in the most physically fit culture in the history of the world. And yet we know this is not true. The sheer amount of fitness-related spending seems to suggest that, culturally, we are more focused on the “jumping weights” than we are on the outcomes associated with using them.

Consider the amount of money spent on gym memberships, fitness clothing, fitness equipment, exercise classes, wearable fitness devices, entry fees for races, athletic events, and the demand for healthy foods. All of this would suggest a culture that puts physical fitness and training at the forefront. But the sad truth is that the fitness equipment in one’s basement is more likely to be used as a clothes rack than for the purposes for which it was intended. Gym memberships are vigorously used in the first weeks of a new year, but often fall out of favor by Valentine’s Day. The reality is that most people fall back into old habits despite the best intentions.

There are similar risks in one’s spiritual life. Attending Mass or worship services on Sunday may or may not have anything to do with the breadth and depth of one’s spirituality. There are approximately 2.3 billion Christians around the world; half of the world’s Christians are Roman Catholics. In the United States, 75 percent of people identify themselves with a Christian religion, and Roman Catholics form the largest single religious denomination in America with approximately 70 million people. According to the Pew Research Center, roughly one-third of adult Americans claim to attend some form of religious service each week. If these statistics are accurate, then there are about 280 million people in the United States alone who are actively seeking to make the kingdom of heaven known on earth. Somehow, intuitively, this seems not to be the case: witness the rush to exit the church parking lot after Mass to see how we tend to compartmentalize our lives of faith.

Today, our predominantly Christian society wants to marginalize matters of faith to a single hour of the liturgy on Sunday. And yet if our faith does not inform and direct the way we lead our lives on the other six days of the week, then what happens at Mass is superficial. It is a parallel point to Epictetus’s urging to “show me your shoulders.” He would say, “Don’t show me the amount you tithe, how often you attend Mass, go to Bible study, or serve in the soup kitchen—show me how your life is different because of the faith you profess.” The shoulders that he would want to see are ones built through the virtues of faith, hope, love, justice, temperance, prudence, and fortitude, and modeled on the Beatitudes Jesus preached in the Sermon on the Mount. After Jesus explains how he expects the lives of his disciples to be different and what the kingdom of heaven will look like, he tells them that they will be recognized by their fruits (Matt 7:17–20)—a close cousin to Epictetus’s charge to “show me your shoulders.” Just as Epictetus could evaluate the effectiveness of one’s fitness program by their physique, the efficacy of one’s spirituality can be evaluated by the degree to which one serves as an instrument of joy, light, healing, unity, hope, and love each day.

In both sports and spirituality, the outcomes and consequences are the only important metric of one’s efforts. The only way one will develop spiritually and physically is through a disciplined, measured, and sustained exertion that is fueled by intentionality. Take, for example, the hundreds of “couch-to-5K” websites and applications to help people get off the couch and into a healthier and physically active lifestyle—in this instance, oriented toward the completion of a 5K race. Of course, a 5K is not the only fitness-related objective one can pursue, but the programmatic nature of these plans points to the fact that getting off the couch and completing a fitness goal is not going to happen by accident, especially after a long period of inactivity. The absence of a well-thought-out plan will likely lead to failure, frustration, or injury—or some combination of all three—regardless of one’s fitness objectives. Something similar can be said in developing one’s spiritual life: Spiritual growth and development requires an effort and purpose that parallels a fitness plan. Holiness does not happen by accident or through osmosis. All of the saints and great spiritual teachers would claim that some spiritual disciplines and practices are necessary in order to grow in holiness.

The most fundamental building block and foundation of one’s spiritual life is prayer. No progress in the spiritual life is possible without it. As the great 20th-century spiritual writer Henri Nouwen wrote in his book Reaching Out: The Three Movements of the Spiritual Life, “when we do not stay in touch with that center of our spiritual life called prayer, we lose touch with all that grows from it.” The 16th-century Spanish mystic Teresa of Ávila warned her sisters against simply reciting prayers or attending Mass without deliberately thinking about their encounter with Christ. She knew that this required effort and discipline because her own prayer life had been, to her own admission, superficial for many years (and the fact that a cloistered nun and Doctor of the Church struggled with prayer should be a great source of encouragement for all of us!).

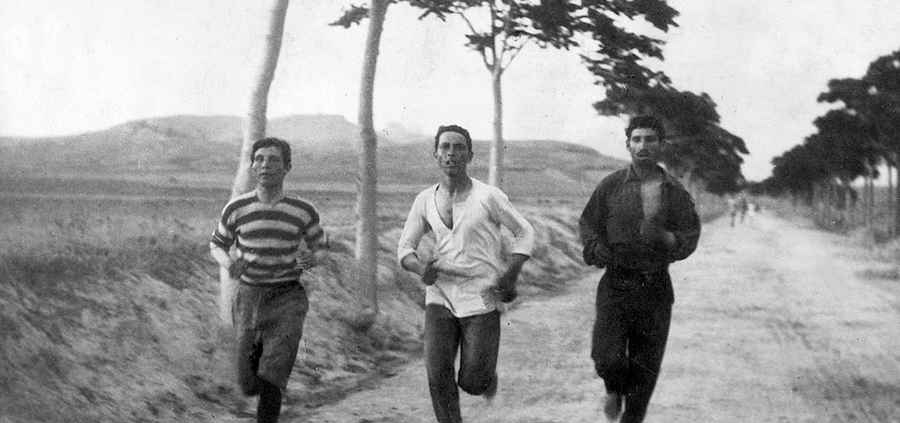

Saint Paul introduced the idea of spiritual fitness in his First Letter to the Corinthians: “Do you not know that the runners in the stadium all run in the race, but only one wins the prize? Run so as to win. Every athlete exercises discipline in every way. They do it to win a perishable crown, but we an imperishable one. Thus, I do not run aimlessly; I do not fight as if I were shadowboxing. No, I drive my body and train it, for fear that, after having preached to others, I myself should be disqualified” (1 Cor 9:24–27). Paul’s intent in this passage is to use physical training as a metaphor to describe the self-control and discipline one needs to grow in the spiritual life. He compares these disciplines with the way an athlete trains and strives for victory in a competition. He is also explicit in reminding us that our spiritual training cannot be “aimless” and without purpose.

Another important point in this passage is the way Paul reminds us that while an athlete strives for a “perishable” crown, Christians are to pursue a crown that is immortal. This crown of immortality and eternal life with God in heaven is the end to which the efforts of one’s spiritual training must be directed. Paul is encouraging the members of the burgeoning Christian community to become spiritual athletes, focused on their training in the same way that athletes would prepare for the Isthmian Games, which were held in Corinth as a part of the Panhellenic Games of ancient Greece. Most scholars will agree that Paul’s first letter to Corinthians was written between 52 and 57 AD, which means that within one generation of Christ’s crucifixion and resurrection, it was apparent that disciples of Christ were called to live a spiritually active life modeled on that of an Olympic athlete.

The Roman Stoic philosopher Seneca once said, “Philosophy teaches us how to act, not how to talk.” Saint Paul would likely concur with this, as he boldly proclaimed that speaking in tongues, prophesizing, and knowledge of God’s mysteries were meaningless without love (1 Cor 13). He even states that a great faith, capable of moving mountains, means nothing without love. But this is not a love that is abstracted from daily life. This is a love that is made real and experienced through patience, forgiveness, and kindness that endures, bears, and hopes in all things, even when there may be no reason to do so.

When the risen Lord appeared to his disciples, he told them that others will know they are his followers by the love they show to one another (Jn 13:35). Anyone who thinks they can live and love in this way without intentionality, without guidance by habits and virtues, is likely to be disappointed. It’s hard work. And it is why, in part, Saint Paul compares the attributes necessary to be a Christian with those required of Olympic athletes.

It is here that one finds the intersection of sports and spirituality. The disciplines and practices that forge and deepen one’s faith are similar to those required for athletic success. Both Epictetus and Saint Paul would likely echo a similar exhortation: Get off the couch, get out of the pew, and live an action-oriented life where others will know your physical prowess by the breadth of your shoulders and your spiritual maturity by the depth of your heart.

Stephen B. Kass is an adjunct professor of Catholic Studies at Seton Hall University, where he teaches a course in Sports and Spirituality for the Department of Catholic Studies. Professor Kass has led numerous retreats, parish missions, and workshops across the country, and has been featured on national Catholic radio programs. He holds an MA in theology from Seton Hall University and served as an officer in the US Navy.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!