The Necessity of Love by Rosalie G. Riegle

Dorothy Day, Thomas Merton, and the

Dorothy Day, Thomas Merton, and the

Greatest Commandment:

Radical Love in Times of Crisis

By Julie Leininger Pycior

Paulist Press, 2020

$29.95 224 pp

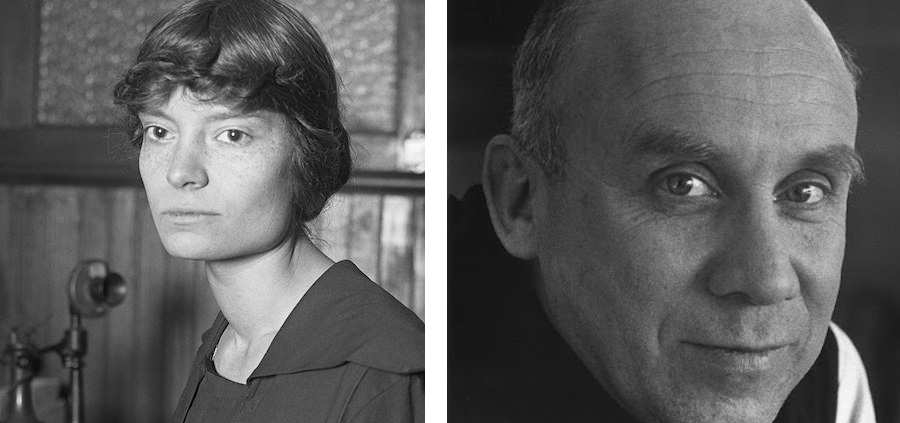

When I spoke on a panel on Dorothy Day and Thomas Merton at the 2011 International Thomas Merton Conference in Chicago, I remember wistfully commenting that all the panelists wished a meeting between the two had taken place. In her new book, Dorothy Day, Thomas Merton, and the Great Commandant: Radical Love in Times of Crisis, Julie Leininger Pycior has conjured such a meeting, setting herself the task of discussing the relationship between Day and Merton in the context of contemporary history. She deftly combines their friendship with their shared work on nonviolent action against war, particularly the Vietnam conflict. She completes her telling of these two figures well, weaving their responses to the world and to each other into the lives of their colleagues as well as to the country as a whole, thus documenting their epistolary relationship while also historicizing it.

Pycior adroitly navigates the antiwar turmoil of the sixties, speaking often of Fr. Daniel Berrigan, who learned from both Merton and Day. Readers unfamiliar with Merton and Day’s many colleagues may find the references to people such as Ammon Hennacy, Fr. Charles English, and Dr. Karl Stern a bit overwhelming at first. There are lots of names to keep track of, as both Merton and Day knew and corresponded with many, many people, both famous and obscure.

As an oral historian, I especially resonated with the several personal interviews the author uses so adroitly. One poignant detail that stood out to me was that it was through Merton and Day’s mutual friend, Fr. English, that the two almost met in 1964. Day had planned to visit Fr. English at Gethsemani Abbey after he suffered a heart attack; however, she finally decided she needed to stay put for a while and spend time in New York with her Catholic Worker family.

Both Merton and Day had problems with obedience, but Merton’s were much harder because he was a vowed monk, while Day was a layperson, and a woman at that. During the period Pycior is writing about, laywomen were accorded little recognition by ecclesiastics in any way, even by censure. Day, unlike her sometime friend Catherine de Hueck Doherty, founder of the Madonna House Apostolate, never asked permission to live as Jesus taught—or felt she needed to ask.

Both letter-writers were apt to react quickly and sometimes acerbically to each other. Merton’s most famous response was his angry telegram blaming Dorothy and the Catholic Worker for the tragic death of Roger LaPorte, a member of the Catholic Worker who immolated himself in front of the United Nations building in 1965 to protest the Vietnam War. For her part, Dorothy would often write about blaming herself, trying to see “the plank in her own eye.” Pycior quotes Day as remembering her mother’s saying, “Least said, soonest mended,” and frequently applying it to issues on which she was asked to comment. In contrast, Merton would sometimes render harsh judgments of others in his letters, especially of architects of war in positions of power.

The book is structured in such a way as to bring out the many aspects of Merton and Day’s correspondence. As its title suggests, suffusing the entire book is the necessity of love. Chapter one, “The One Thing Necessary” explicitly refers to love. Merton first reached out to Day in 1959 and their lively correspondence continued, with some hard interruptions, until his death in 1968. Day was one of the many people who provided a window onto the world that Merton had left when he entered Gethsemani, while Merton provided a confidential sounding board for Dorothy, who frequently wrote of problems with her family or the Catholic Worker movement.

Chapters two and three, “Hopes and Fears” and “Straight but Crooked Lines,” chronicle the growing involvement of both correspondents in protesting the Cold War and counseling nonviolence in the face of an increasingly militaristic church and state. Day criticized her own shortcomings in letters and also on the pages of the Catholic Worker newspaper, which had begun publishing Merton’s antiviolence messages, often under a pseudonym to counter Trappist censorship. Merton approved the formation of the Catholic Peace Fellowship to counsel conscientious objectors and offered a retreat at the abbey on “The Spiritual Roots of Protest” (to which no women were invited, showing some of the prejudices of the time).

In chapter four, “Lives in the Balance,” we see Merton become increasingly involved in writing to the powerful. He agreed with part of the just war position of the Catholic Church, while Day did not. She traveled to Rome to fast and pray and plead for a strong antinuclear position in the documents of the Second Vatican Council.

Chapter five, “A Harsh and Dreadful Love,” tells the story of Merton lashing out at Day for LaPorte’s death. While the two eventually reconciled, this breach of their friendship would haunt Day until the end of her days.

The chapter “One Tremendous Love” gives us a glimpse into the tensions in the family of Day’s daughter Tamar Hennessy, her sorrow at the death of friend and fellow Catholic Worker Ammon Hennacy, and Merton’s experience of falling in love with Margie Smith, who nursed him while he was hospitalized in Louisville for severe back pain. “Kairos: The Providential Hour” shows us how frustrated both Merton and Day were by the slaughter in Vietnam and the US Catholic Church’s official support of the war.

The final chapter, “Not Survival but Prophecy,” gives us what author John Hersey called the “Trip-Hammer Year” of 1968, which saw the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy, as well as Merton’s own shocking death at a Buddhist conference in Thailand. The book’s coda, “The Final Word Is Love,” restates the thesis of this fine book on a more personal note, bringing these two spiritual giants into our own tumultuous time where their voice still rings true.

Those already familiar with Day and Merton will find many new things to learn in this fascinating compendium. In fact, as I began my reading, I initially kept track of all the new details Pycior records. But I soon found there were just too many, and so I resolved to read more on Thomas Merton, using the author’s sound bibliography as a guide. The book is richly annotated with 44 pages of notes, showing that Pycior’s research was both broad and deep, though abbreviations after first mentions might have made the notes more readable. In sum, this book merits close reading for anyone seeking to internalize the joint message of its subjects—the ultimate necessity of love.

Rosalie Riegle wrote her way into the Catholic Worker movement with her oral history, Voices from the Catholic Worker (Temple University Press, 1993), followed by Dorothy Day: Portraits by Those Who Knew Her (Orbis Books, 2003) and two other oral histories on nonviolent peace activists, many of them Catholic Workers. She cofounded the Mustard Seed Catholic Worker in Saginaw, Michigan, and now lives in Evanston, Illinois, where she remains active as a Catholic Worker volunteer.

On the Greatest Commandment:

An Interview with Julie Leininger Pycior

Can you tell us a little about your background as a professor, historian, and person of faith and what initially drew you to the lives of Dorothy Day and Thomas Merton?

Surprisingly, my interest in Mexican American history intersected with my spiritual journey in ways that eventually led me write on Dorothy Day and Thomas Merton. But then, as they both used to say, “God writes straight with crooked lines.”

It all started in 1970, when I was participating in the United Farmworkers grape boycott along with a few other Michigan State students. As a Spanish major active in the MSU Catholic Student Center, I was inspired by the witness of these largely Mexican American labor activists who so often marched under the banner of Our Lady of Guadalupe. [In the] meantime, the most selfless, thoughtful of us UFW supporters, a biology major named Mike McCarthy, had Dorothy Day’s Catholic Worker newspaper lying on the floor of his apartment, even as he had a copy of Thomas Merton’s The Sign of Jonas under his arm while picketing at the grocery stores. Mike’s personal witness prompted me to look into Merton and Day, who soon became the modern American Catholics who most influenced my spiritual journey.

It all started in 1970, when I was participating in the United Farmworkers grape boycott along with a few other Michigan State students. As a Spanish major active in the MSU Catholic Student Center, I was inspired by the witness of these largely Mexican American labor activists who so often marched under the banner of Our Lady of Guadalupe. [In the] meantime, the most selfless, thoughtful of us UFW supporters, a biology major named Mike McCarthy, had Dorothy Day’s Catholic Worker newspaper lying on the floor of his apartment, even as he had a copy of Thomas Merton’s The Sign of Jonas under his arm while picketing at the grocery stores. Mike’s personal witness prompted me to look into Merton and Day, who soon became the modern American Catholics who most influenced my spiritual journey.

Then one day in the 1990s I spied a letter in the Catholic Worker from Mike, who was affiliated with a Catholic Worker community in Michigan, and I decided to get back in touch. Months went by. Finally it was Christmas Eve, so I sat down and wrote to him. Later that day, while I was reaching for something in my clothes closet, a piece of paper fluttered down from the top shelf, where I keep my journals. Amazingly, this scrap, from 1970, was the one entry I ever made about Mike McCarthy. Late that night I lay in bed thinking of how he bore witness to Dorothy Day’s radical vision. Then I recalled that over 20 years earlier he also had introduced me to Thomas Merton, whose inspiring but conversational—almost existential—writing was such a spiritual lifeline. Suddenly it hit me: Merton and Dorothy Day were contemporaries. Did they know each other? I got up and pulled off the bookshelf The Hidden Ground of Love, a collection of Merton’s letters. He wrote to hundreds of people, from all walks of life, but the back cover of that book featured excerpts of his correspondence with one person: Dorothy Day. Reading those letters as Christmas Eve turned into Christmas Day triggered the sole spiritual epiphany of my life—and, yes, sparked the idea for Dorothy Day, Thomas Merton and the Greatest Commandment: Radical Love in Times of Crisis.

Can you speak a bit about how your correspondence with Cardinal Timothy Dolan influenced both the content of his 2012 commencement address at Manhattan College and the references to Day and Merton in Pope Francis’s 2015 address to the US Congress?

Here too, it seems, God writes straight with crooked lines. That Pope Francis spotlighted Merton and Day likely did result from my research, but through an ironic turn of events.

Cardinal Timothy Dolan, the then-president of the US Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB), suggested the Day/Merton topic to the pope after I had recommended that idea to the cardinal for his commencement address at my institution, Manhattan College. But I had originally suggested that Dolan speak on them out of concern over what he otherwise might say. I wondered if he, as a prominent spokesman for the church’s stance against same-sex marriage, might say something that would upset my gay colleagues. Mulling this over as the day of that commencement address approached, it occurred to me that he had obtained unanimous USCCB support for Dorothy Day’s canonization cause, and at the time I was working on this book, so of course I wondered if he also admired Merton. I doubted it, as Merton’s openness to Buddhism was a cause for concern among many in the hierarchy. But an online search of Dolan and Merton revealed that the prelate had referenced the Trappist monk as someone whose writings “enhance our relationship to Christ.”

This, in turn, prompted me to write to the cardinal, telling him that I was doing a book on Merton and Day, thanking him for his own appreciation of them, and noting, “Now you will be speaking to us at graduation . . . [W]hen you speak to us, please speak to us of love: ‘The Hidden Ground of Love,’ as Merton put, or as Dorothy Day wrote, ‘The final word is love.’” He thoughtfully responded to my letter, thanking me for the idea, and in fact made it the framework of his graduation address. “Can I spend just a couple of minutes speaking about love?” he began, then he evoked Dorothy Day and Merton as “two real giants when it comes to love. I mean it, new classmates, when I tell you that I believe that I am now looking out with love and admiration upon today’s Thomas Merton and Dorothy Days.” Then Dolan ticked off the many ways Manhattan College alumni contribute to the betterment of the people in his archdiocese.

Meanwhile, after the pope’s address to Congress, Dolan confirmed to me that he did suggest the Day/Merton idea for that speech. The cardinal added that a number of other prelates weighed in, but Dolan is likely the Day/Merton source, given that a) he was the only cardinal who showcased Day and Merton in a speech prior to the pope showcasing them; and b) given his prominence as Cardinal Archbishop of New York and, at the time, president of the USCCB.

There is much more on this story in the book’s prologue, including how Day and Merton’s lovingly honest attitude toward Cardinal Francis Spellman, the powerful archbishop of New York in their time, informed my approach to Cardinal Dolan.

We are living in a time of widespread institutional collapse, where the structures, practices, and political and economic theories that we have operated under for decades are beginning to give way. In this “time of crisis,” what can the figures of Day and Merton teach us? In what ways is their time similar to ours, and how might their examples of radical charity and contemplation inform our work to build a more merciful and just society today?

Yes, we are whipsawed by so many dire crises. Take, for instance, my reference above to a prominent member of the church hierarchy: that inevitably brings to mind the bishops’ scandalous mishandling of clerical sexual abuse cases. No doubt Dorothy Day, grandmother of nine, would have reacted by crying out in grief to her readers and praying before the Blessed Sacrament with renewed vigor—storming the heavens on behalf of the victims—while Merton would have named that institutional sin for what it is and would have found the right words to honor the injured little ones that Jesus so loved. I suspect that they both would have wanted me to treat Cardinal Dolan with the respect owed any child of God and would want me to recognize that he works devotedly in service to the people of God, but also would have looked for me to acknowledge that, while archbishop of Milwaukee, he had transferred to a cemetery fund money that otherwise would have been available for payment of legal claims by victims of clerical sexual abuse (a revelation that had not yet been reported in the media when he spoke at my college).

Doubtless Dorothy Day would even have gone so far as to call the church “the cross on which Christ is crucified,” for when confronted with ecclesiastical sins, she sometimes did say, “The church is the cross on which Christ is crucified.” She was citing a writer that Merton also referenced, Romano Guardini, as when the monk wrote that Guardini reminds us that we have to remain in a perpetual state of dissatisfaction with the church. At the same time, this priest and theologian is hardly a fringe figure, as he is one of Pope Francis’s favorite theologians and was a mentor to Pope Benedict XVI.

What is certain is that Day and Merton would have prayed for Cardinal Dolan and his episcopal colleagues, recognizing their great need for prayer—this, even as, aware of their own sins, Merton and Day constantly asked each other for prayers. Indeed, they shared an abiding fear of sanctimony, recognizing it as the occupational hazard of any believer. They also remind us that the most important people are “the least.” Indeed, it is from this prophetic pair that I came to understand why the greatest sin is pride.

Meantime, in general, yes, we face crises of almost unimaginable proportions. As I put it in the book’s conclusion:

Today, with humanity itself at risk, we will not be saved by starry-eyed optimism or clever cynicism. We will not even be saved by calculating the effects of our good deeds. As he headed out on the Asian journey where he would meet an untimely death, Merton wrote to a group of friends, including Dorothy Day, “I shall continue to feel bound to all of you in silence and prayer. Our real journey in life is interior: it is a matter of growth, deepening, of an ever greater surrender to the creative action of love and grace in our hearts. Never was it more necessary for us to respond to that action.” Or as Dorothy Day put it, “The final word is love.” In this famous postscript to her autobiography The Long Loneliness, she observed, “We cannot love God unless we love each other and to love we must know each other. We know him in the breaking of bread, and we know each other in the breaking of bread . . . even with a crust, where there is companionship. We have all known the long loneliness, and we know that love comes with community.”

Thomas Merton and Dorothy Day call us to bear witness to the divine and to that spark of the divine in every person, but especially present in the destitute, the ostracized, the attacked (whether by hatred or by war). These two prophetic Americans, who together made history amid the escalating crises of the 1960s, bid us respond to our unbelievably challenging times with a bravery rooted in love: despite everything, and because everything is at stake.

One thing that was fascinating to learn from the book was how Our Lady of Gethsemani, the Trappist abbey in Kentucky where Merton was professed, was a major supporter of the Catholic Worker long before Merton’s arrival. Can you speak a bit about the Benedictine influence on the Catholic Worker movement and Dorothy Day in particular, as well as the ways that Day and Merton exerted a “pastoral role” on each other?

From its inception in 1933 the Catholic Worker movement was influenced by monastic spirituality. Co-founder Peter Maurin hailed from a village in rural France, where the “landscape [was] . . . unified by the church and that heavenly spire . . . a place that you are forced, in spite of yourself, to be a virtual contemplative!” So wrote Merton of the town in that general region where he had resided briefly in his youth. And because the Rule of Saint Benedict says that monasteries should offer hospitality to the stranger, as “another Christ,” Day and Maurin (who would die in 1949) christened their Catholic Worker communities Houses of Hospitality. Of course the Benedictines spawned the Trappists, and it was fascinating to see the numerous admiring donation letters to Day from Gethsemani Abbot Frederick Dunne, as when he wrote of “your great and noble work.” Two years later, in 1941, Abbot Frederick received Merton into the Trappists. By the early 1950s the Catholic Worker was publishing Merton’s spiritual writing, while in 1955 she professed as a Benedictine oblate, or lay associate.

Correspondingly, Merton had known about the Catholic Worker almost since its inception, according to his best friend Robert Lax, who was a student with him at Columbia University in the 1930s. Indeed, the two young men might well have volunteered at the [Worker] if it had not been located at the other end of Manhattan. As it was, they helped out at a similar place that was located near their campus: Friendship House, founded by Catherine de Hueck Doherty, a close friend of Dorothy Day’s. Meantime Lax got to know Day some years later, he told me. She invited him to read his poetry at some of their Friday night meetings, while he took photographs of her being booked by the authorities for refusing to engage in civil defense drills—photos she used in her 1963 book on the Catholic Worker, Loaves and Fishes. The back cover was entirely taken up with a glowing endorsement by Thomas Merton. Doubtless the savvy editors knew that this famous, bestselling Catholic cleric’s good word would encourage people to take a look at this book by a controversial laywoman during the height of the Cold War, when some diocesan newspapers were calling her a “Red.”

Correspondingly, Merton had known about the Catholic Worker almost since its inception, according to his best friend Robert Lax, who was a student with him at Columbia University in the 1930s. Indeed, the two young men might well have volunteered at the [Worker] if it had not been located at the other end of Manhattan. As it was, they helped out at a similar place that was located near their campus: Friendship House, founded by Catherine de Hueck Doherty, a close friend of Dorothy Day’s. Meantime Lax got to know Day some years later, he told me. She invited him to read his poetry at some of their Friday night meetings, while he took photographs of her being booked by the authorities for refusing to engage in civil defense drills—photos she used in her 1963 book on the Catholic Worker, Loaves and Fishes. The back cover was entirely taken up with a glowing endorsement by Thomas Merton. Doubtless the savvy editors knew that this famous, bestselling Catholic cleric’s good word would encourage people to take a look at this book by a controversial laywoman during the height of the Cold War, when some diocesan newspapers were calling her a “Red.”

And yet it was Merton, the person with more status in society, who initiated their correspondence in 1959. He was attempting to respond to a recent epiphany: that his monastic call did not make him somehow more spiritually special, that in fact every single person is beloved by a God who, after all, became one of us. Now Dorothy Day would provide him with crucial encouragement as he sought to combine a life devoted to prayer with writing that, while spiritually rooted, would directly challenge injustice. From seemingly opposite perches, the monk and the movement leader began encouraging each other in their lonely, often-misunderstood call: contemplation and action in service of love of God and love of neighbor. As crises mounted in the 1960s, their shared witness would prove crucial to many thoughtful Catholics and other spiritual sojourners—and with lessons for facing any time of great crisis with integrity.

Through all of this, they consoled and supported one another. A daily communicant who treasured the Bread of Life, Dorothy Day counted on Merton’s prayers as lifted up in his own liturgies and encouraged him in his priestly vocation, while he considered the prayers of her “least” guests the most powerful intercessions of all. This correspondence was made even more touching by their frequent begging of prayers from each other in the face of some crisis or other that they were facing, or that they recognized in society at large—or, often, a mixture of personal and societal angst.

Many of Day’s and Merton’s personal papers were consulted for the first time during the course of your research. Were there any interesting or unique discoveries in your research process, or new perceptions on their lives?

One of the major discoveries was the extent of Day and Merton’s commitment to racial justice—very much ahead of most white Americans. For instance, Day spoke and marched in Danville, Virginia, home to the most brutal police force in the entire South, according to Martin Luther King Jr., even as at that time Merton was writing a pamphlet called “Black Power” for King’s civil rights organization.

On another note: while I was doing my research, Dorothy Day’s diaries were unsealed. It was fascinating to discover, for instance, that she wrote, “I must pray to him” after watching a film of the talk Merton gave just hours before he died. Taken together, their personal jottings bring us into the heart of their spiritual yearnings: she often seeking clarity in her sometimes-chaotic community, he often wishing he could explore other geographic locations for his hermitage. This reinforced my impression that, paradoxically, the monk with the vow of stability was the more mercurial person and the New York City activist, often on the road, was the more deliberate person.

One fun thing I discovered while reading the letters and papers of Day (at Marquette University) and of Merton (at Bellarmine University in Louisville and at Columbia University) was that they had similar, slightly angular handwriting. This impression was confirmed for me by someone who had used the Merton papers for her dissertation and actually had helped Dorothy Day organize her correspondence: Sr. M. Donald Corcoran, OSB Cam. Indeed, Sr. Donald and the other 20+ people that granted me oral history interviews provided wonderful tidbits that help bring the Day/Merton story to life.

While doing research on these two extraordinary but very human figures, did any of their personal limitations become evident?

For all of their prophetic spiritual insights on public policies, [Day and Merton] rarely addressed sex/gender issues. I devote a chapter to exploring their relationship to these questions (including their own sexual attractions). Interestingly, the one who did write, albeit briefly, about women not having full participation in church roles was the male, Merton.

I also devote an entire chapter to their one major disagreement. It centered on a November 1965 tragedy that encapsulates the escalating crises of the sixties: namely, [Day’s] anger when Merton initially resigned from the Catholic peace movement after Catholic Worker Roger LaPorte sat down in front of the United Nations and burned himself alive in kinship with the Buddhist immolation protests in South Vietnam.

Again, though, they were the first to say that they had flaws—sins. Dorothy Day went to confession every week, while Merton’s most famous prayer begins, “My Lord God, I have no idea where I am going . . .”

Finally, how did the process of researching and writing the book, and setting these two figures in dialogue, impact your own spiritual journey?

Their devotion to Jesus’s dictum “Blessed are the Peacemakers” led me increasingly to question the military establishment and our endless wars—much like the journey of my church, with Pope Francis’s peace documents coming close to rethinking the church’s “just war” position. Indeed, the Americans involved in drafting his peace statements are people for whom Day and Merton are guiding lights.

Also, many of these drafters support the Kings Bay Plowshares Seven (KBP7), as do I. These seven Catholic Workers include Martha Hennessy, a granddaughter of Dorothy Day; Liz McAlister, sister-in-law of Day/Merton soulmate Dan Berrigan; and Clare Grady, whose father attended Merton’s peace retreat (It should be noted that Merton expressed some misgivings about property destruction in the name of nonviolence, although his main concern was the use of fire, while the Plowshares protestors pour their own blood, hang peace banners, and sometimes selectively hammer weaponry.)

Also, many of these drafters support the Kings Bay Plowshares Seven (KBP7), as do I. These seven Catholic Workers include Martha Hennessy, a granddaughter of Dorothy Day; Liz McAlister, sister-in-law of Day/Merton soulmate Dan Berrigan; and Clare Grady, whose father attended Merton’s peace retreat (It should be noted that Merton expressed some misgivings about property destruction in the name of nonviolence, although his main concern was the use of fire, while the Plowshares protestors pour their own blood, hang peace banners, and sometimes selectively hammer weaponry.)

The KBP7 were convicted of trespassing and defacing property at Kings Bay Naval Station, the world’s largest nuclear submarine facility. The judge refused to allow them to make their main arguments, including the fact that these weapons which are capable of destroying the entire world, and are obscenely expensive, have been declared illegal by the United Nations. The activists have been sent to COVID-riddled prisons (except for McAlister, who is under house arrest due to her advanced age). “So this is my wilderness,” writes Martha Hennessy in the March/April 2021 issue of the Catholic Worker, “beginning with the baptism of blood on the door of the Strategic Weapons Facility, Atlantic administrative building at Kings Bay Naval Base in southern Georgia . . . I believe the application of our free will to enter a deeply evil place, and offer an opportunity for discussion of alternatives to bombing whole cities and nations, was a healthy step to take as Christian in the 21st century.”

In the process of writing this book, my devotion to contemplation also deepened. I began doing Centering Prayer, including weekly Centering Prayer sessions in a local group affiliated with the Contemplative Outreach of Trappist Fr. Thomas Keating. Along with fellow Trappists Fr. Basil Pennington and Fr. William Meninger (whom I interviewed), Fr. Keating founded this practice so clearly influenced by Merton’s vision of “contemplation in a world of action.” At present my group is meeting online, and we miss gathering in our circle around a candle, but the pandemic does offer one consolation: thanks to Zoom I have been able to join a Centering Prayer group in the Yucatan, tapping my love of lo mexicano. God does write straight with crooked lines.

Meantime, as the world closed down last year and so many of us were isolated at home, as if on a desert isle, I thought of how Merton and Day sometimes considered the desert a place of spiritual renewal. Day wrote appreciatively of Merton’s Wisdom of the Desert, in which he revealed that the ancient desert hermits remind us of “the primacy of love over everything else in the spiritual life. Love in fact is [sic] the spiritual life, and without it all of the other exercises of the spirit, no matter how lofty, become mere illusions. The more lofty they are, the more dangerous the illusion.” And who did Merton say embodied this ancient vision of radical love? You guessed it: Dorothy Day.

Dorothy Day, Thomas Merton, and the Greatest Commandment is available directly from Paulist Press or wherever books are sold.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!