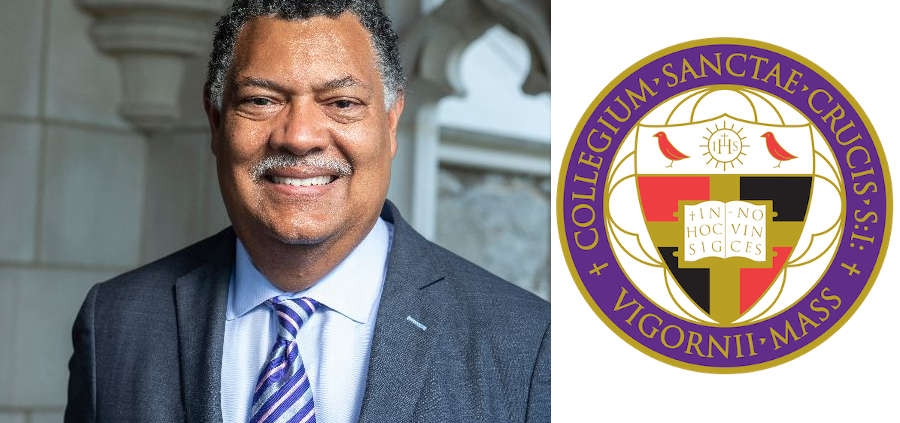

Living a Catholic Life in a Secular World: A Profile of Vincent D. Rougeau by Jane M. Bailey

It is not often a writer has a transformative experience interviewing the subject of a profile, though that’s exactly what happened to me when I zoomed across cyberspace to meet Vincent D. Rougeau, president-elect of the College of the Holy Cross. We were brought together by technology, bounded by the camera’s view. I saw a kind man willing to subject himself to yet another interview about his readiness to take the helm of one of the country’s premier Jesuit institutions as its first lay and first Black president. By the end of our conversation, this brilliant, humble man had shown me how to live a Christian life in a hurting secular world.

By any currency considered—faith, family, intellect, education, or experience—Vincent Rougeau is a wonderful choice for Holy Cross. He is an American legal scholar, dean of Boston College Law School, inaugural director of Boston College Forum for Racial Justice in America, tenured professor at Notre Dame Law School, president of the Association of American Law Schools, and senior fellow of the Centre for Theology & Community in London, England. And that’s only a start!

Throughout his long career, Vincent Rougeau has demonstrated leadership by example and modeled the values that we should hold. Rougeau’s commitment to Catholic Jesuit principles was evident throughout our conversation, within his writings, and through his accomplishments. He makes no apologies for his emphasis on social justice and the need to be focused on the poor and marginalized.

In higher education circles, being a lay leader is the norm. This is not the case at Holy Cross. Rougeau will follow a lineage of clerical leaders and be the first lay president to enter the inner sanctum. When I asked his perspective on lay leadership, Rougeau responded, “I have long believed that lay people have a special role to play in Catholic institutions.” He reminded me that the Second Vatican Council laid the groundwork for institutions to be less reliant on clerical leadership.

It is no secret that the numbers of Catholic clergy are diminishing. According to Georgetown’s Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate, there were 59,192 US priests in in 1970, which dwindled to 35,929 in 2019. The number of lay ecclesial ministers has trended in the opposite direction, with 21,569 in 1990 and 39,651 in 2015.

According to Rougeau, the Jesuits have been preparing for this transition to lay leadership for a long time. Recently, Pope Francis opened key roles for laity in the church, particularly for women. However, getting to the top rung of Catholic academic leadership is no easy feat for a layperson.

Rougeau credits his success to strong family and faith roots in the rural and poor Black Catholic community of southwest Louisiana. During times spent with extended family in those Louisiana parishes, Rougeau absorbed the rich multicultural background of Catholicism and felt a sense of belonging. “There is something very distinctive and rich and empowering about the Black Catholic experience,” he said.

There are many different cultural influences on Catholicism. In addition to the African American influence, “My grandparents grew up speaking Creole French at home and in church, learning all their prayers in French, and being taught by French nuns from Canada, in segregated settings of course.” Later, Rougeau’s grandparents helped found a parish designed to serve the African American community in Lake Charles, Louisiana.

It was African American parishes that finally provided opportunities for Black Catholics to be lay leaders rather than passive participants in the back pews they inhabited in white churches. With sadness in his voice, Rougeau noted, “It is unfortunate so few Catholics understand the rich multicultural history of American Catholicism.” He went on to say, “Even with Baltimore being the mother diocese of US Catholicism and having a large Black Catholic population, I often got the reaction, ‘I didn’t know Black people were Catholic.’”

Rougeau was born in 1963, one year before passage of the Civil Rights Act, which he later credited with transforming his life possibilities. While the act opened opportunities for himself and others, the journey to racial justice has not ended. When I asked if he had any seminal civil rights experiences, he responded, “I was not marked by much racial animus personally, but I knew I was operating under the negative assumptions of Blackness. I knew I had to manage that.”

When his sister was born just two years after him, the priest in the large Chicago parish the Rougeau family belonged to would not baptize her, stating she should be baptized in the African American parish. His mother insisted on staying in their home parish for the baptism and garnered help from the Archbishop of Chicago to make that happen.

His family lived as one of few Black families in white neighborhoods in the ’60s and ’70s in Chicago; Cambridge, Massachusetts; Queens, New York; and later in Silver Spring, Maryland, outside of Washington, DC. The family experienced many slights and ways of being excluded. “As persons of color, we knew we weren’t always welcome and were forced to endure things that weren’t fair. You just did it. You recognized how important it was to succeed.”

The seeds of Rougeau’s character were sown before he was born. His father, a civil rights activist, was arrested at age 19 while demonstrating for integrated lunch counters and consequently expelled from Southern University. He continued his civil rights activism and graduated from Loyola University Chicago in 1967. By age 30 he had graduated from Harvard Law School. Sixteen years later, Vincent Rougeau would earn his own juris doctor degree from Harvard Law after graduating magna cum laude from Brown University.

Recounting his formative years, Rougeau acknowledges, “I was privileged to be protected from experiencing some of the injustices my parents had to endure. We were able to be sheltered. My parents’ strategy was to move into areas of the best public schools.” He attended public school in Montgomery County, Maryland, and received his religious education from CCD classes in the large Catholic parish his family attended. While there were very few African American families in the parish, it was an ethnically diverse and international congregation.

His father’s legal and political work in Washington, DC, and later his own professional experiences there, exposed Rougeau to the international community of power and politics. His father was legislative assistant to Senator J. B. Johnston and subsequently worked in the Carter Administration. Rougeau himself spent two undergraduate summers as an intern for Senator Johnston and began his law career in Washington.

It was during his first academic position as law faculty at Loyola, his father’s alma mater, that he went through a tortuous period of discernment as to how to best utilize his gifts and talents. The culture of Loyola nurtured introspection, and from that grew Rougeau’s commitment to Jesuit Catholic liberal arts higher education.

I was curious if being a person of color was the wellspring of Rougeau’s commitment to social justice, but he pointed instead to his Catholic belief. “As a Catholic, I have been drawn to the message that Christ was attentive to those in need, the forgotten people. If you are in a position of privilege and do not realize injustice, you haven’t been fully formed.” Rougeau makes clear it is not enough to realize injustice. We are called to act by using our gifts and talents to be in service to those in need.

To that end, Rougeau serves as senior fellow to the Centre for Theology & Community in London. The Centre’s mission is to equip churches of different faiths to transform their communities of need, such as London’s East End, through shared community organizing and theological reflection. Pope Francis’s new book, Let Us Dream, was the basis for their recent international conference, “A Politics Rooted in the People.”

Rougeau uses a gentle voice of reason when he talks and writes, even on controversial topics such as where he believes American Christianity has gotten off track. In his 2008 book, Christians in the American Empire: Faith and Citizenship in the New World Order, Rougeau discusses what it means to be a Christian citizen and proposes that the dignity of a human person can only be realized in community with others.

When I asked how he plans to incorporate Catholic social teaching at Holy Cross, he responded, “I want the college to be a place of vibrant conversation and intellectual debate. Our country is in an exceedingly difficult place. We cannot dehumanize each other. If you empty the other of his/her humanity you are losing your way. We need to include people with whom we disagree at the center of our conversation. As a Jesuit Catholic institution, we have to remember the vision of Christ in the Gospels as to who we should be as followers.”

We began to talk about how the Holy Cross community will maintain its Catholic identity amid secularization of society. As he did throughout our conversation, Rougeau balanced challenge with opportunity, though his voice resonated with the word opportunity. His holistic vision is something of a Catholic social and spiritual-evangelical project. “I think the Jesuit Catholic intellectual tradition has a lot to offer,” he said. “It is rich and meaningful so I’m not too worried about the numbers.”

Rougeau does not see the life of faith and the life of the intellect as being mutually exclusive. “An education that doesn’t recognize we are spiritual beings is not a full education,” he explained. It does not matter to him whether students come to Catholicism, or just come to respect what Catholicism brings. It does matter who we are within our communities and how we treat one another despite our many differences.

Holy Cross is 75 percent white, 4 percent African American, and a remaining multicultural mix. Rougeau will need to grapple with how to make Holy Cross attractive to students of color and how to make sure they are embraced when they arrive on campus. He noted, “We need to be prepared for a multicultural future where everyone is not going to agree or hold the same faith beliefs. My job as an educator is to see that [students’] education gives them the tools they need to live in the future.”

At the end of the interview, I asked Rougeau if he had anything else to add. He thought for a moment and then went back to his Louisiana roots. “I would offer a particular thank you to my grandparents for their extraordinary faith and commitment in the face of all kinds of difficulty,” he said. “It was from a place of deep commitment and love that they passed down the values I’ve been talking about.”

Vincent Rougeau’s life honors his family, who put their hearts into opportunity, success, hope, and change. Soon he will pay that forward, providing a Jesuit Catholic education to a new generation of Holy Cross students who, he hopes, will lead us into a multicultural future that provides a seat at the table for all.

Jane M. Bailey is a writer from Litchfield, Connecticut. You can find more of her work at JaneMBailey.com.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!