The Priest and the Iconographer: A Portrait of William Hart McNichols by Michael Ford

“There’s a childlike awe in being called to create along with the Holy Spirit,” explains Father William Hart McNichols as he works away in his “messy studio” in the New Mexican city of Albuquerque where he also serves as a priest for the Archdiocese of Santa Fe.

It’s been said that the vocation of an artist is to send light into the human heart and, over the course of 30 years, Father Bill has done just that, emerging as a leading international figure in his field. Now his icons and sacred images are commissioned by individuals, families, and churches across the globe.

“People often say icons seem sad to them but they’re not,” he points out. “They’re really imploring and begging for compassion. I’m trying to cause a metanoia or change of heart in the person looking at them.”

Trained by the Russian-American master, Brother Robert Lentz, O.F.M., Father Bill has produced more than 300 mystical works of art, noted for their vivid hues and broad range of subjects. They include over 80 portraits of the Mother and Child, icons of the ancient saints of history, and images of more contemporary figures who have often paid with their lives because of who they were or what they stood up for.

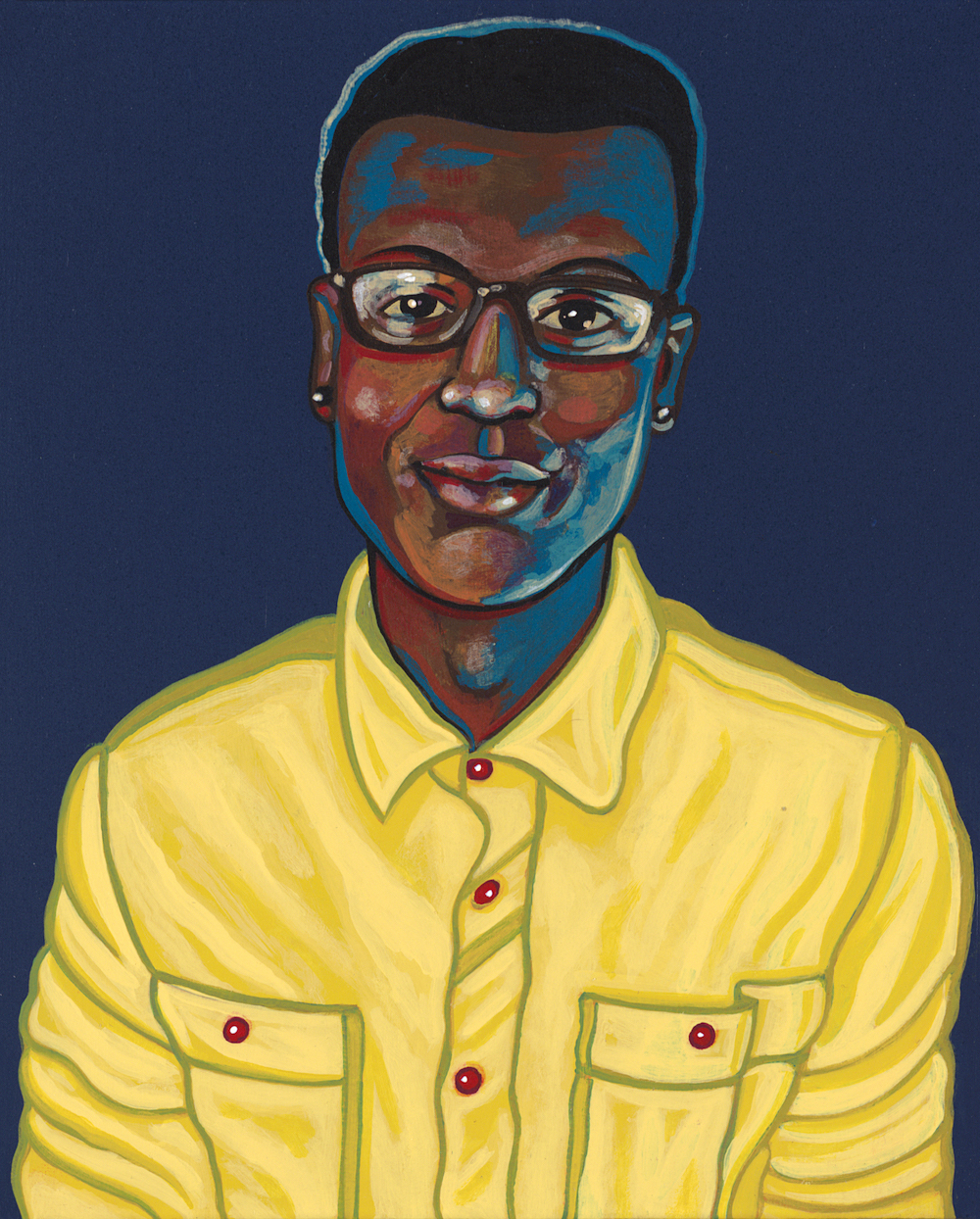

Perhaps not surprisingly, there have been calls for Father Bill to create images of George Floyd, the 46-year-old African American killed during an arrest in Minneapolis, or of Breonna Taylor, the 26-year-old African American medical technician fatally shot by police officers in Louisville. But Father Bill didn’t feel called in quite the same way as he was to paint Elijah McClain, a young black man who died in police custody in Colorado in 2019.

“A friend of showed me his photograph and, as soon as I saw it, I thought ‘Oh my God! I have to do him.’ Technically it is an image since he’s not canonised. It’s just 8 by 10 inches so it only took me about a week to complete.” The result is a tribute to “a very gifted, talented and beautiful soul.” Father Bill added light around his head and a golden-coloured shirt to echo scripture’s prophetic words about the chosen ones of God. The red buttons signify his terrible death, red being the color of the martyrs.

William Hart McNichols, “Elijah McClain,” acrylic on wood, 2020

Following the murder of 20 children and six staff members at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, in 2012, Father Bill sent his icon of Santa Rosa of Lima, patroness of the Americas, to the Catholic parish of Saint Rose in Newtown. Deeply disturbed by the killings, he hoped it might function as a healing image for members of the community.

Painted before the tragedy, it could be interpreted as a prophetic picture. Santa Rosa stands on the earth in her lay Dominican habit with her feet on the northern part of the Americas—and her left foot happens to be close to New England. The intercession of Santa Rosa, says Father Bill, offers not only healing but also transformation for the world.

Although many of the people he features may have died in dark and harrowing circumstances, Father Bill believes it’s essential to bring out their luminosity because “they are already in heaven.” This was memorably the case with the Orthodox martyr Hieromonk Nestor. A priest-monk during the closing years of the Soviet Union, he was found dead at the age of 33 outside his house in Zharky, Russia, with his throat slit and multiple stab wounds. “If you’re praying with an icon of Nestor, you are praying with him as he is now in heaven,” he insists. “You aren’t looking at a McNichols painting; you’re looking at Nestor. When you commission an icon, you’re ordering the subject not the artist. Most icons are never signed because iconographers believe the Holy Spirit did them.”

While Father Bill prefers not to dwell too much on suffering, it is sometimes difficult to avoid. With Demetrius of Thessaloniki, the early fourth-century Christian martyr who was lanced with spears, there’s obviously a cry of pain on the face. Most of his images tend not to concentrate on torture unless the focus is the Cross—and, even then, not in too much detail.

Father Bill’s subjects include followers of other religions, among them Mansur Al-Hallaj (858–922), a Persian mystic in the Sufi tradition of Islam who was imprisoned and brutally dismembered in public. Father Bill places him in his cell the night before his execution. He wears robes with the name “Allah” inflamed on his heart, symbolising his passionate love for God. Others feature Saint Josephine Bakhita, the religious sister born in western Sudan who was kidnapped at age seven, enslaved, and tortured; Princess Diana, “friend of the sick, outcast, and victims of violence”; Matthew Shepard, a 24-year-old gay man entrapped and then killed on a deer fence in Wyoming in 1998; and environmental writer Nicholas Black Elk, a second cousin of the war leader Crazy Horse, who guided nearly 400 fellow Native Americans, including children, into the Catholic Church.

Naturally, iconographers have to relate to their subjects and, understandably, Father Bill feels closer to some than others. One of his larger and most striking pieces was inspired by a woman to whom he has been devoted for nearly 40 years, the German mystic Saint Hildegard of Bingen. Titled Viriditas: Finding God in All Things, it was created for the Environmental Sustainability Center at Loyala University in Chicago. Honouring Hildegard’s theology, that the greening power of God (“viriditas”) makes all things new, it sends a powerful message to politicians for today’s urgent ecological concerns. As Father Bill puts it: “There’s no life without a planet.”

Since the age of 24, Father Bill has loved the writings of Julian of Norwich, but he had never attempted an icon of her. When he finally received a commission, he felt a relationship was already in place. But if Father Bill is less familiar with the person he is painting, he researches meticulously, as in the case of Sister Dorothy Stang, the American missionary and activist shot in the Amazon rainforest. “I really had to read about her, go into her life and try to figure out how I was going to picture her,” he explains.

“It’s different with Jesuit, Franciscan, or Dominican subjects as I’ve had a strong relationship with all three. When I did Fra Angelico, the patron of artists, I already knew a lot about him. The same with Catherine of Siena. I knew she had to hold the papal tiara because she is the protector of the papacy. But I put a crown of thorns on the tiara to tell people that, when you get called to be a pope, you don’t get the crown you think you’re going to get—you get the crown of thorns.”

For World Youth Day in 1993, Father Bill personally presented a more traditional icon, Our Lady of the New Advent, to Pope John Paul II when he visited Denver where the artist grew up. “As I approached the dais where John Paul was seated, he immediately stood up and approached the icon, with his hands outstretched. I had not always agreed with him, but after our brief meeting I felt unshakably connected.”

The son of a former governor of Colorado, William Hart McNichols spent hours as a child drawing and colouring in his bedroom, while also devouring books about the saints or the young martyrs of the Roman catacombs. He painted his first Crucifixion when he was five.

Such was his spiritual sensibility that, from an early age, Father Bill felt a mysterious bond with Saint Francis of Assisi. “When I was six or seven, my parents went to San Francisco and brought me back a statue of Francis,” recalls Father Bill, himself a Third Order Franciscan. “It was all white porcelain with birds on the arms. I really loved him. I think that Francis is the closest thing the Catholic Church has to what the Russians and Greeks call a holy fool. Francis was approachable. I’m not sure if it was anything to do with being Italian, but there was that part of him where he would just do spontaneous things. That really touched me. People would just back away because he was so filled with emotion and devotion. But he wanted women and men and everybody to be part of his life.”

It was, however, Saint Ignatius of Loyola who became Father Bill’s spiritual guide when he entered the Society of Jesus in 1968. He studied philosophy, theology, and art at St. Louis University, Boston College, Boston University, and Weston School of Theology in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He furthered his art studies at California College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland, California, and later received a master of fine arts in landscape painting from Pratt Institute in Brooklyn.

Four years after being ordained in 1979, he began a pioneering healing ministry with the AIDS hospice team of Saint Vincent’s Hospital, Manhattan, during which time he also illustrated 25 books, mainly for children (“which gave me a lightness and a joy”) while caring for people who were seriously ill. He even published a remarkable book, Stations of the Cross for a Person with AIDS, which contained original drawings based on Christ’s hands.

During these months of Covid-19, Father Bill, who is now in his early 70s, has been making comparisons with that ministry in the 1980s and the world of social distancing today. “The quarantining is different now,” he points out. “We didn’t have to do that back then and we could go to any place to eat. I was able to celebrate healing masses with a congregation. I was seeing a lot of people so it wasn’t as isolating. We never did find a cure for AIDS and they never found a vaccine. We lived seven years without that so going through something, without having a clear sign when it’s going to be over, is not abnormal for me. I was pretty lucky to have experienced those years because I know how to exist in a pandemic.”

In 2002, as the scandal of sexual abuse by clergy swept across the United States, Father Bill defended gay priests against what he saw as unjust scapegoating, a public stand which led to his leaving the Jesuits without having taken final vows. It was an extremely sad and painful experience, but one which called him out into a full-time iconographer’s vocation.

These days Father Bill isn’t able to paint for the eight hours expected of him as a younger artist. In the beginning, Brother Robert Lentz apparently shocked him by insisting that if Father Bill didn’t agree to paint for that length of time, he wouldn’t teach him. “So I prayed for the grace and I got it,” he remembers. “Without Robert, I would never have treated it like a full vocation. Robert gave me an entirely new life. But I’d never have had the nerve to spend my life doing it if I hadn’t done seven years’ work with those people in New York.

“I gradually got into a rhythm, painting in the evenings when it was quiet and I could create a mood. I used to work from 5 p.m. to midnight. One of the costs is physical. From sitting in that same position for all those hours, I have to really exercise the right side of my body and stretch to keep it going—and I experience problems with my right hand too. These days, in the evenings at 7, I’ll put on music and light candles, then I’ll paint for three hours. Right now I’m doing Our Lady of Silence so I ask myself: ‘What is that manifestation of Mary and how do I make the icon serene?’”

For this remarkably gifted, gently spoken, and profoundly sensitive iconographer, holiness clearly manifests itself in many different guises. “What you gaze upon, you become,” he says. “The icon is also looking at you.”

* * *

Additional icons by Father Bill are available on his website. A documentary about Father Bill by Chris Summa, The Boy Who Found Gold, is available here.

* * *

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!