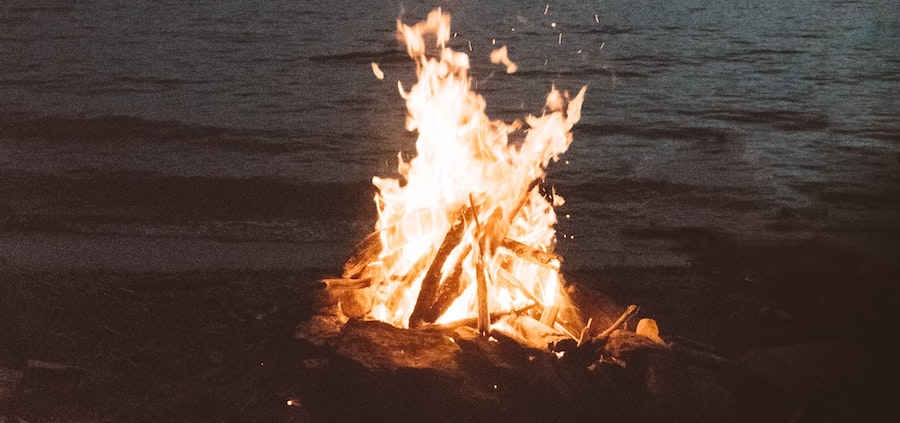

Sacred Fire by Ed Burns

“I came to bring fire to the earth, and how I wish it were already kindled! I have a baptism with which to be baptized, and what stress I am under until it is completed! Do you think that I have come to bring peace to the earth? No, I tell you, but rather division! From now on five in one household will be divided, three against two and two against three; they will be divided:

father against son

and son against father,

mother against daughter

and daughter against mother,

mother-in-law against her daughter-in-law

and daughter-in-law against mother-in-law.”– Luke 12:49–53

In chapter 12 of the Gospel of Luke, Jesus says some very disturbing things—things we may not wish to hear, things that, to say the least, do not sound very comforting. Is this not something of a contradiction? Isn’t our faith supposed to be a source of consolation? And yet here we have Jesus saying that he comes not to bring peace to the earth, but division. This is not only between warring nations, but within the very intimacy of family life and relationships: fathers against sons, mothers against daughters. What is going on here? Isn’t Jesus supposed to be the Prince of Peace?

Well, yes, of course. But there are certain things we must remember about the Prince of Peace and our faith in him. In the first place, Jesus never was nor ever claimed to be the Prince of Peace-at-Any-Price. Nor is a genuine faith in Jesus primarily intended to produce warm and fuzzy feelings of inner security and well-being. There is, after all, a “cost of discipleship,” as Dietrich Bonhoeffer and many other Christian believers discovered during the Second World War. Sometimes discipleship can cost someone his or her life. This, I suppose, is why we frequently pray “to deliver us from evil,” as we do in the Our Father.

Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, a prominent civil rights leader in the 1960s, once wrote: “Well-adjusted people think that faith is the answer to all human problems. In truth, however, faith is a challenge to all human persons. To have faith is to be in labor.”

What Rabbi Heschel meant by this is that the achievement of a mature and genuine religious faith is likely to be the fruit of struggle and the work of a lifetime. Our Christian faith can often create more problems for us and raise more doubts and questions than it can solve. Our faith does not contain quick and easy answers to life’s dilemmas. What solutions there are to such dilemmas may need to be worked out in the loneliness and anguish of one’s soul. It ought not to come as a surprise to hear of a Jesus who experienced some of this very loneliness, anguish, and frustration in his own efforts to bring about a new vision—his own vision of life and meaning and purpose for humankind. For Jesus, holding fast to this vision was clearly a source of labor and stress: I came to bring fire to the earth . . . and what stress I am under until it is completed.

What is this fire of which Jesus speaks? Is it a fire of destruction? Anyone vaguely familiar with the person of Jesus described in the Gospels will recognize that this is not the case. It was Jesus himself who said that he was sent to seek and to save that which was lost (Luke 19:10); that he had come to give his life for the ransom of many (Matt. 10:28); that it is not the healthy who need the physician but the sick (Mark 2:17). Therefore, when Jesus says that he has “come to bring fire to the earth,” he is not speaking a word of threat or destruction, but a word of empowerment, a word of purification, a word of strength and encouragement for his disciples.

Jesus has come to make us earnest, dedicated, and effective followers of the Gospel values he proclaimed, to make us strong in our convictions and courageous in speaking truth to power. He has come to shake us out of our boredom and lethargy and complacency, to challenge us to a greater commitment to seeking those things which will deepen and increase our dignity and our common humanity, and to awaken within us a renewed sense of mission and purpose and meaning in our lives. “Some day, after mastering the winds, the waves, the tides and gravity, we shall harness for God the energies of love, and then, for the second time in the history of the world, man will have discovered fire,” wrote Teilhard de Chardin; Christ has come to enkindle within us this “fire of love” that will renew the face of the earth. It was this fire that he was so eager to bring to earth that caused him such stress for the duration of his mission.

If all of this is true, then how, in the same breath, could Jesus speak of the divisions and conflicts that would occur for those who would be faithful to his word? What does love have to do with conflict? Here we must ask ourselves: Is it an easy thing for those who profess faith in Jesus and commitment to his Gospel to actually live the values contained therein? Are Gospel values the same as those that dominate our American culture? Do we think that there should be no conflict in our lives, no division, no struggle, no time where we would have to choose one set of values over another, one way of life over another, one personal relationship over another?

Jesus certainly encountered conflict throughout his life. His message of love and nonviolence challenged people at the deepest levels of themselves, beneath their surface securities. He made people choose one way of life over another, and he didn’t leave them much wiggle room. He who is not with me is against me (Matt. 12:30): He could not have said it more simply. Nor did he promise his followers a primrose path: In the world you will face affliction, he said, though he quickly added, Take courage, I have overcome the world (John 16:33).

The words of Jesus are like fire if we take them into our own hearts. They can purify us, embolden us, enable us to discern true prophets from false (“I have heard what the prophets have said who prophesy lies in my name, saying, ‘I have dreamed, I have dreamed!’ . . . Let the prophet who has a dream tell the dream, but let the one who has my word speak my word faithfully. Is not my word like fire?” [Jer. 23:25, 28–29]). They can help us to distinguish idolatry from authentic religious worship and commitment. They can help us sort out superficial ego-driven ambitions from more mature motivations and intentions. They can help us differentiate fantasies of omnipotence from realistic and humble acknowledgement of our human limitations. And they can help us recognize the distinction between truthfulness and “truthiness,” between candor and propaganda, between strong moral leadership and infantile lust for power.

The words of Jesus can act like a compass pointing unerringly toward the gracious heart of God. They are words that can and ultimately will lead us through the divisions and conflicts that afflict us into a kingdom where God will be “all in all,” and where we shall learn to love our neighbor as ourselves. It is this kind of love that is God’s gift to us, that frees us from lives of competition and self-concern, that enables us to return love to God, and that can bring the hostilities that divide us to an end.

Ed Burns is a licensed marital and family therapist living in Litchfield, Connecticut, where he maintains a private practice treating individuals, couples, and families.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!