A Process of Discernment by Joe Pagetta

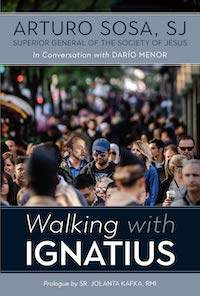

Walking with Ignatius

Walking with Ignatius

By Arturo Sosa, SJ

in Conversation with Darío Menor

Loyola Press, 2021

$24.99 264 pp.

When my grandmother died some 30 years ago, my parents and extended family went through the bittersweet process of dividing up her possessions. We lived in the same house as my grandmother, up in the second-floor apartment, and there was one item I asked my mother if I could have: a framed lithograph of Christ on the Mount of Olives by Josef August Untersberger. It hung in our furnished (and completely wood-panelled) basement where many of our Sunday dinners took place, and later, where I practiced with my first band. It now hangs over the doorway in my kitchen.

I knew the story it represented, often referred to as Jesus at Gethsemane or the Agony in the Garden, and was struck by how human Jesus appears at that moment. I don’t think I walked down the stairs into my basement once in my young life and didn’t notice it. I’ve always interpreted the scene, which takes place between the Last Supper and his arrest, as Jesus being tempted, though there’s no indication in either of the canonical gospels of that happening. Only that he is praying.

Thanks to Walking with Ignatius, a new book by Arturo Sosa, SJ, Superior General of the Society of Jesus, in conversation with Rome-based journalist Darío Menor, I have a new interpretation. In a question about St. Ignatius Loyola’s crises, including his thoughts of suicide prior to his conversion, Sosa responds:

The transformation that conversion involves can’t be experienced without times of deep crises, as the Gospels demonstrate. In this context, the most dramatic depiction of this is the agony in the garden where Jesus completely abandons what Ignatius might well have described as “his self-love, will, and interest.”

That’s the moment, Father Sosa suggests, that Jesus, through his own freedom, consecrates himself to God. It’s a conversion, not a temptation. It’s also about prayerful discernment and time for prayer, two concepts, along with faith as a personal choice, that dominate Menor’s interview with the 31st Superior General. Seen in this way, Jesus chastising Peter, James, and John for falling asleep while he prays is much more than a lesson about whether we, the faithful, are present and awake to God’s message (which is how I’ve heard it discussed in countless homilies). It’s about Jesus desperately needing time to pray, and the space to do it. Note that he keeps moving further away from the disciples to be alone in his discernment. Time is the prevailing theme. In Mark 14, Jesus prays that “the hour might pass from him” and tells Peter to “keep awake and pray that you may not come into the time of the trial.” He finally tells the three of them, “The hour has come.” He is human, like us, and aware of the fateful hands of time.

Discernment comes up throughout the book, in what feels like Father Sosa’s answer to almost every question. In Chapter 2, “Arturo Sosa: A Pilgrim Today,” in what’s almost a lighthearted inquiry into how Father Sosa handles the pressure of leading the Society of Jesus (“the largest male congregation in the church”), his response is measured:

Rather than a feeling of power, I have a feeling of responsibility, of being obliged to take decisions, which arise after a process of discernment rather than according to the first idea that comes into my head or what might seem a good idea to me personally. There needs to be a process that involves discernment. This isn’t something private, and it demands an effort.

Pope Francis, the first Jesuit pontificate, speaks of discernment often as well, and I imagine Menor reading my mind when he asks Father Sosa in Chapter 4, “A New Dream for the Church,” “Discernment is one of the most oft-repeated words of this pontiff . . . is this only a buzzword?”

“Without discernment, there is no experience of God,” Sosa responds, “and just the same, we cannot speak of discernment without prayer.” He continues:

The most interesting Old Testament characters are people of discernment. And the great work of Jesus involves getting all of us to discern. He does not offer ready-made answers but breaks down our own constructs and discerns the truth with the Father from a place of common sense. Before taking any major decision, he first listens to God through prayer.

My spiritual director, Fr. Bruce Morrill, S.J., often asks me if I’ve talked to Jesus about whatever it is I’m struggling with, and reminds me that the solution, or the direction I need to take, may not reveal itself immediately. It may not come the first time I pray about it, or the second, but the repetition and the time dedicated to the question may dictate my path. He’s introducing me, little by little, to Ignatius Loyola’s Spiritual Exercises, something he and Father Sosa know well and practice at least once a year, as is the tradition of the Society of Jesus.

“Their name is not a random choice,” says Sosa in response to a question by Menor about the greatest strength of the Spiritual Exercises. “We exercise to be in shape. In this case, we are doing exercises in the Spirit so we can train in the process of accompaniment that helps us discern.” Later, Sosa clarifies the role of consistency in truly making the Exercises effective. “The Spiritual Exercises . . . teach you to retain a certain discipline in order to preserve time for prayer.”

To set aside this time for prayerful discernment, of course, is a choice. As is Christianity itself, Sosa reminds us. For this cradle Italian-American Catholic, this is the most powerful revelation in the book. For many of us, Christianity, and specifically Catholicism, is a birthright. We were born into it, which may not necessarily seem like a choice. But in order to truly accept it, and the relationship with God it offers, we must actively choose it, whether that comes through a conversion born of the Spiritual Exercises or a comparable retreat experience, the way we make decisions every day of our lives, or simply noticing God’s presence in our lives—all of it, ultimately, deepening our relationship with God.

“In the Bible, we see that God communicates with human beings by revealing rather than imposing his presence on them,” Father Sosa says in response to a question by Menor about the Society’s First Universal Apostolic Preference, “Showing the way to God.” “The Lord becomes present, he offers himself to us, but each individual is then free to accept or reject him.” A few questions later, he clarifies: “We need to show a way but never impose it, because a Christianity that is not freely chosen loses its meaning.” And elsewhere: “Love is not about imposition but attraction, an offer, patient(ly) waiting for an answer that is freely given.”

I think of Untersberger’s painting on my basement wall all those years before my grandmother died, my kitchen wall now, and all the walls it’s hung on in between. I consider what it meant to me then and what it means to me now, and how its story and my relationship to it has changed over time. It would not be an exaggeration to say it’s been with me as long as I’ve been alive, which is as long as I’ve been Catholic. Reading Walking with Ignatius, like reading any book, is a choice. But through Menor and Father Sosa’s insightful questions and answers, complemented by chapter-ending invitations to prayer inspired by the Spiritual Exercises, it’s much more—a book that carries with it an opportunity to deepen your faith, and choose Christianity all over again.

Joe Pagetta is a museum professional, arts writer, and personal essayist whose work has appeared in America, Ambassador Magazine (the National Italian American Foundation), Chapter 16, Wordpeace, Ovunque Siamo, and more. He has a B.A. from Saint Peter’s University and currently serves as the director of communications for the Tennessee State Museum in Nashville, Tennessee. More at JoePagetta.com.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!