Positively Chrystie Street: The Catholic Worker in the Mid-Sixties by Jim Wilson

The times in 1965 were certainly changing. The Catholic Worker at 175 Chrystie Street in New York City, a few blocks from the Bowery, was certainly a part of those changes.

The young men and women at the Catholic Worker at this time in history were facing major issues in their lives. These young people set an example for elders, priests, nuns, and those who would come after them. Dorothy Day recognized their importance, as did the Berrigan brothers. I want to take some time to share what I remember about life at the Catholic Worker in 1965 and 1966 as well as to celebrate the names and stories of those mentors, peers, and heroes who I knew.

First, some brief background: the Catholic Worker was founded and established in 1933 by Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin. There is plenty that has been written about those early years and the two founders. How the organization actually operated, however, has always been a work in progress. Dorothy and Peter based the philosophy of the Catholic Worker on the principles of personalism and Christian anarchism. The overriding concept is one of a community sharing work and responsibilities to meet the needs of marginalized people and the poor by providing food, shelter, and clothing. In this environment, there were few rules and as little bureaucracy as possible, unlike government-funded programs that require eligibility verification, certification, and the like.

There was some basic organization to Saint Joseph’s House of Hospitality, the official name for the Catholic Worker residence on Chrystie Street, in 1965. The proportion of young people to older volunteers at the Worker at that time was high. This was due to the reality of the times. Young men were facing decisions about the draft, and young women were searching for what role they should be playing in a world screaming for social justice, peace, and equality. The Catholic Worker became a place where these issues could not only be discussed, but where actions could be taken.

A number of the more senior volunteers had established clear areas of responsibility for themselves. Walter Kerrel was in charge of the office and mailroom on the second floor. There he and his sidekick Smokey Joe handled the daily mail and the monthly paper. Walter also handled responsibility for distributing small amounts of cash to various regulars and volunteers. Ed Forand was in charge of making sure that a variety of staples were available for the kitchen and thereby for the soup line and the dinner meal. Ed and Walter would work out the costs, and Ed would do the shopping. Chris Kearns was in charge of the house’s only vehicle. Since he had the keys and was the driver, he was responsible for collecting vegetables at the wholesale market. This required dickering and begging the various vendors to donate vegetables that were on the cusp of spoiling.

The rest of what needed to be done was either unassigned or up for grabs. There was usually a core of 6 to 10 volunteers who split up these other tasks. They included daily preparation for the soup line early in the morning. Later in the day, there was prep for the evening meal as well as cleanup duty. There was also a clothing room where donated clothing was sorted and given out to people on a daily or as-needed basis.

Another aspect of hospitality was building relationships, talking to people, and assisting with problems or issues. “Keeping the peace” could take time and skill, depending the situation and the people involved. There were guests who sometimes would not get along. Fights or shouting matches could take place fairly quickly, and a negotiated peace needed to be brokered.

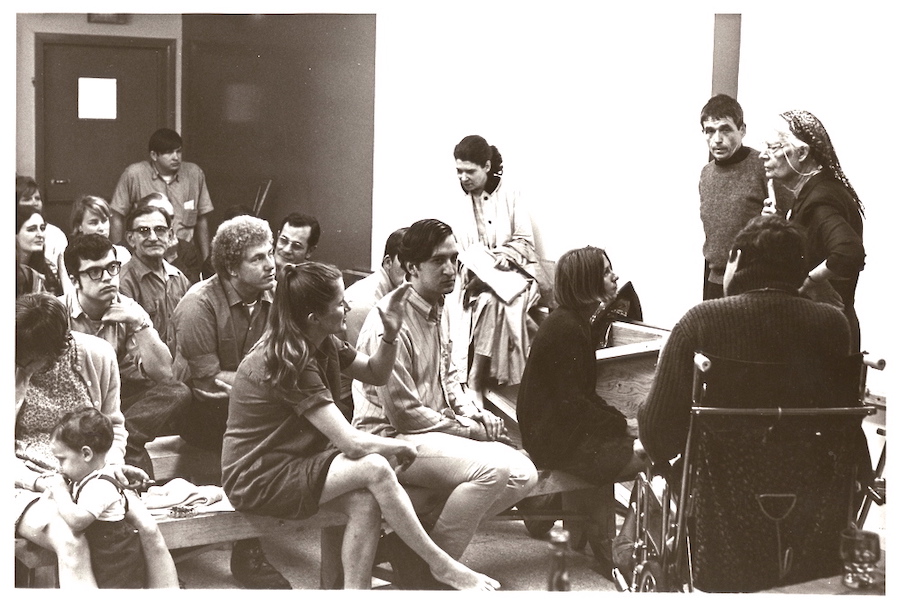

Dorothy Day and Dan Berrigan speaking to a group of Catholic Workers. (Photographer unknown; courtesy Jim Wilson)

One of the first people I met at the Worker was a young woman a few years older than me by the name of Nicole d’Entremont. Nicole was quiet and determined. Peeling potatoes, preparing soup, making sure coffee pots stayed full—these were the tasks I saw her perform every day in a straightforward fashion. Nicole came from Pennsylvania. She had been to Selma with a contingent of others from the Catholic Worker earlier in the spring. Nicole was also a wonderful writer and intellect. Dorothy Day recognized her gifts, and soon Nicole was writing articles for the paper on a regular basis.

Two other people showed up at the front door one day, Murphy Dowouis and Paul Mann. They had traveled by train and the use of their thumbs, carrying guitars and duffle bags from a recent stint at the Joe Hill House in Salt Lake City, Utah. That house of hospitality was operated by Ammon Hennacy, a personalist, anarchist, pacifist, and regular troublemaker of sorts. It was also where Murphy and Paul met up and sang with Bruce “Utah” Phillips.

Murph, or “Cajun” as we called him, grew up in Louisiana. He was actually a Cajun and had been involved in peacemaking and civil rights work since getting out of high school. Being a peace activist and civil rights proponent in Louisiana in the early ’60s was no small feat. Besides picketing and marching, he used music and songs to tell stories about workers of every sort. He was a terrific musician and played a wonderful 12-string guitar. Cajun had come east to see and experience the New York Catholic Worker, but also to become more involved in demonstrations against the war in Vietnam. He was actively refusing to cooperate with the Selective Service system.

One morning Murph was on his way to the Catholic Worker and made it as far as Delancey Street, a few blocks away, when suddenly four or five men in suits grabbed him, cuffed him, and took him away in their car. The FBI had gotten their man, but Murph didn’t make it easy. He went limp and had to be dragged into the car. He spent a few years in federal prison in the deep South. I never saw him again until I found a video he made just prior to his death. He was a close personal friend of another fellow from Louisiana, the great mystery author James Lee Burke.

Paul Mann came from the same area in Pennsylvania as Nicole. They had grown up and gone to school together. Paul was another young man refusing to cooperate with the draft. He was a “down-home” kind of fellow, cut in the mold of Woody Guthrie, one of his personal heroes. He also played a mean guitar, and he and Cajun could keep a crowd entertained for hours. At some point Paul and I became roommates in one of the Catholic Worker apartments. We also became close friends, walking the streets of New York late at night, going to Chinatown for fried rice with a copy of the Times right off the press. Paul eventually married Salome, a beautiful artist and dreamer who occasionally volunteered at the Worker.

Raona Millikin became involved at the Worker, volunteering while a college student. She eventually left school and became a full-time volunteer. Raona and I were married in the middle of our protests against the draft. Paul Mann served as my best man. Although we eventually separated, Raona stuck by me through many difficult times.

There were so many others, all committed young people who wanted to bring change to the world. Phil and Sheila Maloney were a married couple who ended up managing Saint Joseph’s House. David Miller and Cathy Swann were both volunteers who eventually married. After David’s draft card burning, court battles, and prison time, they opened a house of hospitality in the Washington, DC, area. Dan Miller, Dave’s brother, also found his way to the Catholic Worker.

Barb Uhrie, who had been involved with the Worker for some time, married Al Uhrie, a committed antiwar activist who was tragically murdered on the street near his home. Ursula McGuire was a former Maryknoll nun who had spent time in Africa prior to her involvement with the Worker. Roger LaPorte was a former seminarian working part time at Columbia University and volunteering for various shifts at the Worker, always offering friendly conversation to people who needed it. Tom Hoey was the youngest of the volunteers. He was taken under Dorothy’s wing and supported in finishing high school.

Isidore Fazio was an older person who had spent many years around the Worker. He had become disillusioned with the way things operated but always came back to share a meal, a cup of coffee, or to help out where needed. Isidore was always searching and stretching the thinking of the younger Catholic Workers. Terry Sullivan was also a bit older. He had been an original Freedom Rider and had worked with Karl Myer, who had a house of hospitality in the Chicago area. Terry led philosophical discussions and arguments that could go late into the night. Felix McGowan was a former Maryknoll priest who had served as a missionary in Latin America. He had left the priesthood and was working for peace and social justice through writing, organizing, and demonstrating.

We were a very tight and close-knit community. We would work hard during the day and into the evening. Then we would gather in someone’s apartment, have some beer or wine, and sing our hearts out. Music was something that brought us together, and whether it was our own singing or hearing someone else at a small club or bar in the East Village, we followed the melody. We shared a belief system around the liturgy, the Eucharist, and in the social teaching of the church. We didn’t just sing labor and antiwar songs; we sang songs as part of a joyful liturgical celebration. Dorothy participated when she could. She preferred traditional religious celebrations, but she understood that changes were coming and she did her best to be a part of our experiences.

Eventually prison and life’s circumstances separated many of us from one another, but there were always those who stayed in touch, who found each other and reconnected whenever possible. We became doctors, lawyers, arts and music professionals, nurses and HIV/AIDS activists, a professional photographer, authors, poets, farmers, professors, nonprofit administrators, counselors and social workers, librarians and ex-cons. Wherever we went, whomever we became, the principles espoused by the Catholic Worker were woven into our lives.

Jim Wilson spent time at the Catholic Worker in the mid-60s. This piece is a chapter from his autobiography and memoir, Choosing the Hard Path, that will be published in early 2022.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!