Remembrance Institutions by William Droel

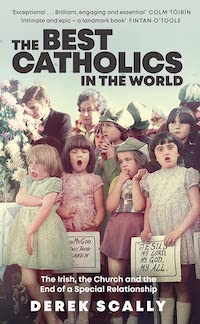

The Best Catholics in the World:

The Best Catholics in the World:

The Irish, the Church and the End

of a Special Relationship

By Derek Scally

Penguin Books, 2021

$32.95 336 pp.

The unifying theme of this report is abuse of children by clergy and religious. The book, however, is not an exposé, not a victim’s account, not a manifesto, not an attempt “to apportion blame or pronounce sentence.” Instead, author Derek Scally wants to thoroughly understand recent turns in Irish Catholicism and their relationship to the past. His tools are his own memories, literary allusions, examination of old catechisms, visits to schools and churches, participation in exhibits, and historical research and several interviews, including with Cardinal Sean Brady, Marie Collins, a champion for abused children, and Paddy Doyle (1951–2020), an abuse survivor and disability activist.

Why bother? Scally admits that everyone he met during the three years of preparing his manuscript is exhausted after “years of revelations, scandals, pain and confrontation.” Yet he is convinced that if Ireland fails to deal with its past, more structural flaws will certainly result in similar tragedies. This pertains not only to Catholicism, he wisely says, but “to how we deal with repeated serious failings in our healthcare system, to how we manage our housing crisis, to how we meet our obligation [to those] seeking refuge, to our attitude and conduct towards the weak, the old, the vulnerable.” The temptation in all of these areas is to settle into “lingering silence,” occasionally interrupted by “ritualized arguments” that go nowhere. This temptation quietly enters through the back door and creates a practiced helplessness, a pervasive victim mentality.

Scally concedes that people can reasonably become ex-Catholics. It is not healthy, however, for individuals to unreflectively just walk away from their Catholicism. To leave “does not absolve you of responsibility to try and understand,” he writes. An impulsive exit only tightens “a lid on discussion.”

In 1850 Archbishop (later Cardinal) Paul Cullen (1803–1878) convened the Synod of Thurles. The Great Famine was in its last months. The suppression of Catholicism in Ireland was in the rearview mirror. Cullen moved Catholicism past its homemade and irregular practices to a functional organization. His synod became “a sign of hope” for “a new prosperity and respectability.” Its decisions filled “deep-seated needs in the people for order, safety, pride, education and economic security.” The synod standardized practices and set off an expansion of ministries. It included a burst of building projects and a lively show of Catholicism through “expensive, elaborate rituals, overseen by tight, top-down structures.” It was a grand success. “There’s much to be proud of” in Catholic Ireland’s past, Scally writes.

The foundation built in 1850 determined “the shape, scale and ambition” of Ireland in the 20th century. The church’s respectability, however, was of a Victorian type. Behind the façade of Irish Catholicism was an obsession over sex as unholy. Jansenism, an import from France, added to a preoccupation with sinfulness for a “shame-based society.”

Ireland’s top-down Catholicism was one of presence but not of critical thinking. To be a Catholic, for lay and clergy, was to participate in many devotional and social events without really knowing much about scripture or doctrine. It was faith in an institution, an institution doing many fine things in education, social services, and healthcare. But without a substantial encounter with Christ and dogma, it became a lazy church. “The shallowness of many people’s religious belief allowed prosperity and secularism to erode Catholic Ireland’s foundations with great speed,” Scally concludes. The abuse of children took away the veneer of the confidence placed in institutions. Little was left. Disaffection soon followed disillusionment.

Now 44 years old, Scally has been based in Berlin for 20 years as a foreign correspondent for the Irish Times. He is aware of how Germany is processing its Nazi history. He proposes similar “remembrance institutions” for Ireland where some people were abusers, some were victims, and many were bystanders—all of whom “should feel a responsibility . . . to inform themselves of what made the unthinkable possible.”

In his wandering about Ireland, Scally comes upon some small beginnings. Interestingly, it is through the arts that Ireland’s recent past is being examined. Playwrights, poets, photographers, painters, and musicians are lifting up Ireland’s experience of shame and sorrow and tentative reconciliation. At one point in the book, Scally attends a reception for women who survived the Magdalene Laundries. It is an imperfect attempt at healing, he finds, but it is a start. He mentions a promising theological institute in Dublin where a small number of Catholics are able to talk through their experiences within a full tradition of faith.

The contours of Catholicism in the United States have largely been imported from Ireland—at least in northern cities. Thus, many of Scally’s observations apply here. Any renewed Catholicism for the United States requires as serious a confrontation with the past as it does for Ireland. Such an examination will not be limited to clerical abuse and mismanagement of deviant personnel. It must include the good and the bad: Catholicism’s part in slavery and with race relations; the content and presumptions of its religious education; its culture around holy sexuality; its regard for feminism; its participation in democracy. The “responsibility to try and understand” begins with the bystanders. It is a task for all of us who are Catholic, especially to include those who are half in and half out. ♦

William Droel is a board member of the National Center for the Laity (PO Box 291102, Chicago, IL 60629).

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!