Mission by Mission: A Soldier’s Journey of War, Faith, and Healing by Jane M. Bailey

The Frog Hunter:

A Story About the Vietnam War, an Inkblot Test and a Girl

By TB Stamper

Milton Barn Press, 2021

$15.99 ($4.99 Kindle) 370 pp.

Not every author can write beautifully about the hell of war. Writer TB (Bart) Stamper is one of them. He kept me turning the pages of his book, The Frog Hunter: A Story About the Vietnam War, an Inkblot Test and a Girl, straight through to the end and left me breathless in the process.

A memoir is only as good as its ability to carry the reader along with the author. Stamper brought me with him to boot camp, paratrooper and Ranger training, onto the plane to Vietnam, into the crucible of fear and fire fights, onto the choppers, and into the face of death. In the tradition of Vietnam memoirs like Robert Mason’s Chickenhawk and Michael Herr’s Dispatches, it is a harrowing ride that covers the full spectrum of human emotion.

Fighting our way through the war’s moral morass, Stamper showed me, with his lyrical writing, how war wounds the soul. He writes of a night reconnaissance mission, lying still on the ground, listening to the enemy patrol searching for him, their boots softly breaking branches, close enough to touch. He relays that “Tiny maggots of fear multiplied, eating away at my courage. Squinting forcefully, I squeezed the sweat from the corners of my eyelids, fighting to concentrate and stave off the chewing worms.”

I was there with him, waiting for our date with death.

When he brought me on the plane home from Vietnam, I sat with an anguished soldier burdened with a vault of memories too painful to open for the next 12 years. We got off the plane and I wanted to run, far and fast, from the war. But for Stamper, the devastating effects of combat had embedded themselves and there was no escape. He returned to stateside duty in California and headed for a collision course with his superior officers.

I was swept along in his desperate search to find truth. Turning to the hippie culture, he realized the peace movement wasn’t always so peaceful after all, and his footing slipped. Finding love, and the Rock on which to plant his boots, gave him the foothold he needed to heal.

Stamper introduces me to his personal God. He is not the God of my imagination nor my denomination. This is an intimate God who comes after a broken soldier. He forgives sin, unlocks vaults, and heals wounds. As I turn the last page, I am immersed in hope. Stamper has found a higher, more wondrous way.

The Frog Hunter lays the truth of war on the line and offers a means to peace through faith forged in war’s aftermath. While it moved me deeply, it also left me feeling contrite as to how little I know about the Vietnam War, soldiers’ lingering pain, and my own faith. With this in mind, I requested an interview to understand the man behind the book. Stamper graciously agreed. We got together on a beautiful winter morning. His home was warm and welcoming, with a distant view of Connecticut hills.

Stamper is quiet, serious with a quick wit, and has a Ranger-steady temperament of grit and determination. When asked how he was able to write such a gut-wrenching book, he replied, “Ernest Hemingway once said, ‘All you do is sit down at a typewriter and bleed.’” He continued, “While I was in Vietnam, I kept a photo album with snippets of writings, thoughts, drawings, and poems. For the next 50 years, the war, mission by mission, poured onto legal pads, spiral notebooks, scraps of paper, or napkins until I finally organized the writings into the book that was published in October.”

God is an important component of The Frog Hunter, yet the title doesn’t indicate that. It takes a while for the reader to find God in the rubble. I asked why this was so.

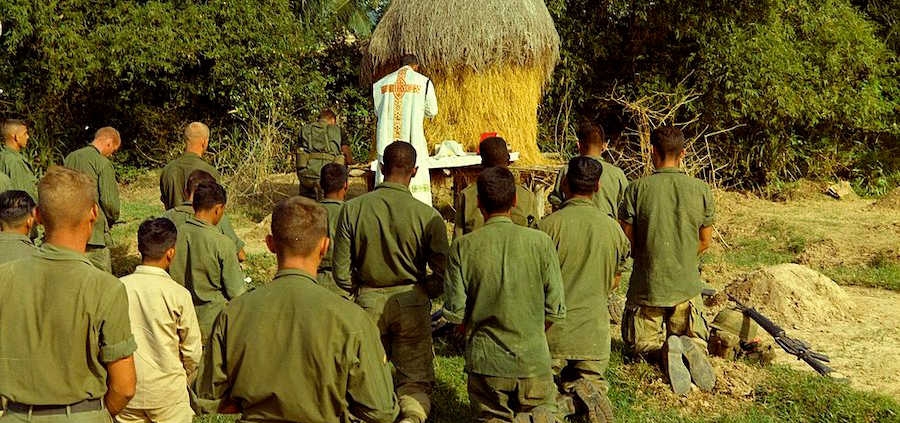

Charlie Team, November Rangers, Vietnam, 1969. TB Stamper is standing on far right

“The story is about a tumultuous three-year period in my life: before, during, and after Vietnam. A God-thread appears in the prologue and continues through to the last page. At times we see a hint of him, or his shadow, then he crashes through the veil unexpectedly. It was important to reveal God in my book exactly as he revealed himself to me in my life. I have been a Christian now for 50 years, and he continues to reveal himself to me every day through his Word.”

When Stamper talks about his faith, his voice is strong and his eyes pierce, as if to say, “I know what I’m talking about. Don’t dismiss this.” He has a belief that appears born of a lifetime with God. Yet Stamper did not grow up religious, and did not attend church. “My parents had a 50-pound gold-colored Bible that sat unopened on the coffee table. I think it was there as a nod to God, hoping he might see it and bless our house.”

When asked how his beliefs developed, he said, “As a child, I believed there was a God, a benevolent creator of the universe. One look at the night sky told me that, but I didn’t really know him. As a teenager, I was squarely in the driver’s seat of my own life and barely gave him the time of day.

“In Vietnam, I developed the habit of praying, no begging, God to let me survive. The chaplains conducted weekly services at our firebase. One for Catholics, and one for Protestants. I attended both for a short while, until my friends started to get killed, then the enormity of the war overwhelmed me and I stopped going.

“By the time I came home, the war had destroyed all that I thought to be true and the desperation in my soul set me on a quest to find truth. What I didn’t realize is that through it all, God was drawing me to himself. We have a pursuing God who desires we be in a relationship with him.”

The first chapter of The Frog Hunter shows Stamper living a fun-loving life straight out of American Graffiti, complete with hot rods and Friday night drag races. This is juxtaposed with an awareness of the war and the approaching draft. Stamper says he was naïve about everything at the time. His patriotism was tempered by images of body bags on the nightly news. It was after seeing John Wayne in The Green Berets that he got a decision-making jolt. “The film tapped into my patriotic fervor and pumped testosterone straight into my 18-year-old veins,” he says. Three hours later he was in the Army recruiting office.

Vietnam complicated the Catholic Church’s already uneasy relationship with war and peace. An argument that Vietnam was a “just war” had its origins in Pope Leo XIII’s 1891 encyclical Rerum Novarum, where he denounces “the main tenet of socialism, community of goods” as “directly contrary to the natural rights of mankind” (§15). The church was divided between those committed to Gospel nonviolence and a vocal anticommunist flank represented in the U.S. by Cardinal Francis Spellman.

In 1967, U.S. President Lyndon Johnson visited the Vatican to implore Pope Paul VI to facilitate dialogue between the United States and Hanoi. Johnson saw the pope as both an enemy of communism and a persistent voice for peace—after all, he had famously admonished, “No more war, war never again” during his 1965 address to the United Nations.

The Vatican was influential in persuading Hanoi to begin early peace negotiations. On January 27, 1973, “An Agreement Ending the War and Restoring Peace in Vietnam” was announced to a divided America. Many of us at the time were naïve enough to believe that peace meant peace. But while American troops came home and bases were closed, the war continued. Two years after the peace agreement, communist forces ended the war by seizing control of South Vietnam and the country was unified as the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. It was a bitter pill for soldiers like Bart Stamper.

“I think the ones who understand the cost of war most are those who have been touched by it directly,” he told me. “The whole point of soldiers going to war is so civilians don’t have to experience it. However, the people who should never be oblivious to the cost of war are the politicians who send our solders into harm’s way.”

Stamper said he was most proud of the incredible heroism of the men with whom he served in the November Company Rangers, 75th Infantry, 173d Airborne Brigade. He tempered that by saying he was least proud of the way our government conducted the war. His voice got quiet and quivered with anger. “It cost men their lives.”

In The Frog Hunter, Stamper recounts reading a newspaper two years after his return from Vietnam where he learned that the North Vietnamese Army had advanced into Binh Dinh Province and the town of Bong Son had fallen. It was a few miles from LZ English, where his Ranger unit was stationed—where he and his buddies fought and died. “I stopped reading and threw the paper down,” he writes. “Those turncoat politicians! We had the victory-in-hand and they’re just giving it away!”

During our conversation he expanded on that. “It is well documented that Congress gave the war away during and after the negotiated peace by breaking their promise to support the South Vietnamese by not sending them the supplies they needed to defeat the North. In doing so, they invalidated the sacrifices of all who died and were wounded; the sacrifices of their families and loved ones; and turned their valiant efforts into waste. A quarter million South Vietnamese soldiers were killed and two million civilians murdered. Here it is, almost 50 years later and the veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan, who sacrificed so much, watch things crumble like Vietnam, with their sacrifices also invalidated.”

When asked what advice he has for the younger generation of soldiers, Stamper’s voice cracked. “Twenty-two vets a day kill themselves. That’s nearly one per hour.” He took a minute to compose himself, pain evident.

“I’d tell returning soldiers, God knows what you went through. He was there. And he is with you in your arduous journey home. If you feel the ground beneath you is crumbling, know that there is firm ground ahead. A Rock on which you can plant your boots. That Rock is Christ.”

Stamper’s advice to politicians is simple. “God put you in authority to do the right thing. We are all accountable to God for our actions. Weigh your decisions carefully.” His words recall those of Pope Francis, who writes in the conclusion to his 2021 collection, Peace on Earth: Fraternity Is Possible, that questions of conscience “should disturb the political leaders who will answer before God and the people for the continuation of wars.”

As for advice to the church, Stamper replied, “You want to fix the world’s ills? Stop embracing the culture, telling people what they want to hear and trying to be liked. Give people the beautiful, unvarnished Gospel. Christ died on the cross to save us from our sins. His sacrifice is the only thing that transforms the human heart.”

Author TB Stamper today

The Frog Hunter’s prologue and epilogue are bookends to Stamper’s evolving relationship with God. From its first hints to its deepening convictions, this relationship emerges within the thicket of war and Stamper’s tempestuous return to civilian life. It coincides with falling in love with his lovely wife of 50 years. Stamper says that “The Frog Hunter is my story. It’s the story of God’s incredible love for us all.”

Stamper smiled at me, clearly at peace with having told his very difficult, very personal story in his book, and in our conversation. His son, who is a professional filmmaker, stopped the camera that had been recording us, his gracious wife made us lunch, and their beautiful home came back into focus.

What’s next for Bart Stamper? “Going to the grocery store,” he replies with a grin. His son doesn’t let him off the hook. “Should we tell her about our project, Dad?”

“Oh, we’re planning a trip cross-country to film the stories of my November Ranger Company buddies. Incredible things happen in war. I want to get their stories on film.”

Before I read The Frog Hunter, my knowledge of war was abstract. I knew war is hell; I just didn’t understand what hell is. I am grateful that Bart Stamper leaned into his pain and wrote his way out. He gave me the visceral truth about war, its aftermath, and a path to solace through the Savior who walks side-by-side with broken humanity. Bart leaves me with words from Psalm 46:1. “God is our shelter and strength, always ready to help in times of trouble.”

If only we’ll listen.

Jane M. Bailey writes from Litchfield, Connecticut, about matters of the heart and people who make a difference. To see more of her writing, go to JaneMBailey.com. To learn more about TB Stamper, see SoulRanger.com.

I think to understand war and its consequences, it is as necessary to talk to the civilians caught in a war’s crossfire as it is to the soldiers who do/did the fighting. I also think that those of us who came of age during the Vietnam war will, in some ways, always be debating what we did and/or didn’t do during that time. Maybe that is as it should be. Maybe we have learned something. Maybe it will make us better judges regarding any government’s wish to pursue war as a solution.