Love Proposed from Below: Recovering the Russian Orthodox Tradition of Peace

For those of us with a deep love of Russian Orthodox spirituality, the events of the past month, heartbreaking enough on their own, have brought additional grief. We mourn the warping of the Russian Orthodox faith for nefarious nationalistic ends. We see Patriarch Kirill’s capitulation to the violent messianism of Vladimir Putin as a tragic case of succumbing to a false god. We pray for the intercession of saints like Seraphim of Sarov, the monk who fed bears by hand outside of his hermitage in the forest, who pleaded with a judge for mercy on behalf of a group of robbers who beat him senselessly and left him for dead, who counseled his followers to “Acquire a peaceful spirit, and thousands around you will be saved.”

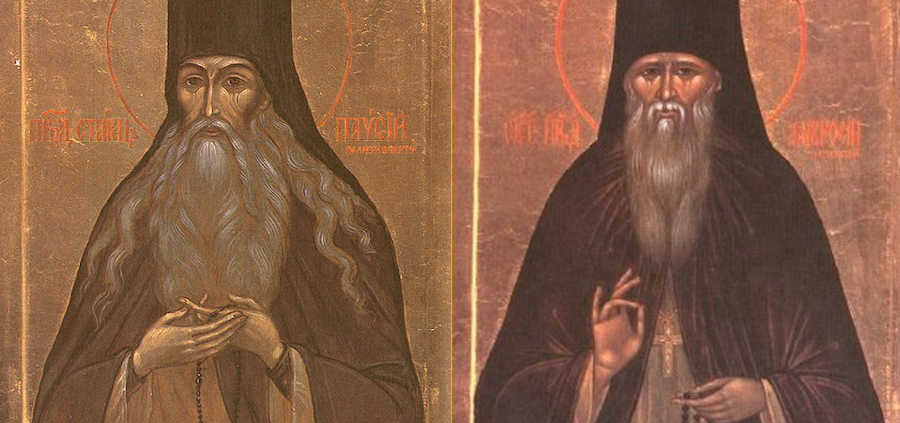

In the early days of the invasion, I kept a book of icons open on my desk. On the verso page was an icon of Saint Paisy Velichkovsky, a Ukrainian by birth, and on the recto, Saint Ambrose of Optina, a Russian. There is a gentleness in Saint Ambrose’s eyes that is hard to put into words. The icon itself, even in reproduction, seems to quiver with tenderness, as though the saint were on the verge of tears. Ambrose was the model for Father Zosima, the spiritual father to Alyosha Karamazov in Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov. One phrase from this fictional character contains more truth than all the sham sophistries of our real-life warmongers:

Every one of us is undoubtedly responsible for all men—and everything on earth, not merely through the general sinfulness of creation, but each one personally for all mankind and every individual man. . . . Only through that knowledge, our heart grows soft with infinite, universal, inexhaustible love.

Or this, which seems especially prescient given the Russian justification for the war as defending “traditional” Christian values against a decadent, secular West:

Hate not the atheists, the teachers of evil, the materialists—and I mean not only the good ones—for there are many good ones among them, especially in our day—hate not even the wicked ones. Remember them in your prayers thus: Save, O Lord, all those who have none to pray for them, save too all those who will not pray. And add: it is not in pride that I make this prayer, O Lord, for I am lower than all men . . .

In a speech at the dedication of the Pushkin Monument in Moscow in June 1880, Dostoevsky addressed the theme of “Holy Russia” and Russia’s special mission to the world. Though some of its reactionary, religiously nationalistic language has not aged well, and its calls for a nebulously defined “universalism” threaten to erase the particularities of human persons, Dostoevsky’s speech is notable for its language of nonviolence:

To become a true Russian, to become a Russian fully, (in the end of all, I repeat) means only to become the brother of all men, to become, if you will, a universal man. . . . our destiny is universality, won not by the sword, but by the strength of brotherhood and our fraternal aspiration to unite mankind [emphasis mine].

It is not through conquering or invasion, but through a sort of radical humility (“Let our country be poor, but this poor land ‘Christ traversed with blessing, in the garb of a serf’”) that the Russian aspires “to include within our soul by brotherly love all our brethren, and at last, it may be, to pronounce the final Word of the great general harmony, of the final brotherly communion of all nations in accordance with the law of the gospel of Christ”. Love proposed from below, not violence imposed from above, is what will rectify the divisions between nations and bring about lasting peace.

In addition to praying for the victims of the Ukrainian invasion as well as all victims of war, I find myself praying that Patriarch Kirill will experience that softening of heart so palpable in the icon of Saint Ambrose. I return to words of another patriarch, Ignatius IV of Antioch, who expressed a vision for “a church that does not maintain itself in a survivalist conservatism and in an ethnic and linguistic particularism, a church dispersed like salt, seeking its identity in its vocation.” This is the church we so desperately need today: one that is unafraid to make itself small, to break itself apart into humble daily acts of service, to resist the rhetoric of centralizing nationalisms. Pope Francis expressed as much in a phone call with Kirill earlier this month. Rejecting the justification of the invasion as a “holy war,” he said, “The Church must not use the language of politics, but the language of Jesus.”

Michael Centore

Editor, Today’s American Catholic

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!