“A Sublime International”: The Life and Work of Léon Chaine by Gregory Fox

In 1973, the French historian Émile Poulat proposed that, in the future, a study ought to be conducted on fin-de-siècle liberal Catholics in Lyon, France, noting that “everything remains to be done about this period, about this history.” While what follows is not such a study, it is a small attempt to bring into focus a sadly little-known figure in the history of Lyonnais liberal Catholicism: Léon Chaine (1851–1941).

Alongside other liberal Catholics in Lyon, Chaine was involved in some of the most important cultural and political conflicts of his time, most especially the Dreyfus affair. During this period he opposed antisemitism, fought against the exaggerated militarism and nationalism that was en vogue among the Catholics of his day, and vigorously campaigned for reform in his church.

Early Life

Léon Chaine was born February 22, 1851, in Lyon to a bourgeois Catholic family. According to Pierre Pierrard’s 1998 study Les chretiens et l’affaire Dreyfus, the Chaine family was “deeply Christian and deeply liberal.” The family produced a number of priests who played important roles in the religious life of Lyon. For example, Léon’s nephew, Fr. Joseph Chaine, became professor of New Testament exegesis on the Faculty of Catholic Theology at Lyon Catholic University; another nephew (also named Léon) became a Jesuit priest and later opposed the Nazi occupation of France.

Unlike these members of the Chaine family, Léon was not destined to become a priest. Instead, as a student at École Saint-Thomas d’Aquin-Veritas in Lyon, he took a different route and pursued a career in law. Founded in 1833, École Saint-Thomas d’Aquin-Veritas was deeply marked by the Catholic liberalism of the Dominican Jean-Baptiste Henri Lacordaire. All four of the school’s founders, including Léon’s uncle Fr. Pierre Chaine, were adherents of the Catholic liberalism of Lacordaire, which emphasized a dual commitment to Catholicism and the principles of the French Revolution. While at the school, Léon was “imbued,” as Pierrard puts it, with “l’esprit de Lacordaire.”

Facade of the Soufflot Building, École Saint-Thomas d’Aquin-Veritas

This liberal Catholic influence was apparent in the day-to-day life of the school. Students, for example, were not required to go to Mass daily, but only on specific days. This was not done to encourage religious laxity. Rather, according to Léon, it was done to encourage a sense of “liberty compatible with the character of the [school],” since “so many young people who have graduated from ecclesiastical institutions abandon religious practices . . . and no longer go to Mass at all, having been forced for years to attend it every day!”

In the area of education, the École Saint-Thomas d’Aquin-Veritas was unique as well. It contrasted profoundly with what Léon describes as the éducation servile of other authoritarian and illiberal forms of Catholic education. For example, he writes that “the directors of [this school] sought to enlighten their pupils, to exercise their freedom for which they showed great respect” and that “they . . . believed that they had neither the duty nor the right to deprive the young people . . . of any faculty of critical thinking.”

The environment of the École Saint-Thomas d’Aquin-Veritas clearly left its mark on Chaine. He would recall his time there fondly: “We have spent, we say, with these venerated masters, men of faith and science, the happy years of our youth.” Without a doubt, the enlightened Catholic atmosphere of the school played an important part in shaping his attitude towards the pressing problems of his day.

On November 15, 1879, a year after he started his career as a lawyer in Lyon, Chaine married Marie-Louise Quinson in Tenay. He lived quietly during this time, and nothing during this period seemed to point to him becoming involved in public controversies. This all changed during the Dreyfus Affair.

Opposing Antisemitism

When the Jewish army officer Alfred Dreyfus was (falsely) accused of treason in 1894, the reaction in the Catholic world was, with a few exceptions, unequivocally against Dreyfus. Many of the leading figures of the anti-Dreyfusard movement were Catholics, such as the “pope” of antisemitism, Édouard Drumont, who ran the violently antisemitic newspaper La Libre Parole. Catholic newspapers such as La Croix published articles that fanned the flames of antisemitism and French nationalism. In fact, opposition to Dreyfus was not limited to the right, for it spanned almost the entire Catholic political spectrum, from Catholic royalists to certain abbès démocrates (“democratic priests”). To be a Catholic and believe that Dreyfus was innocent “had become like . . . the eighth deadly sin”, as Chaine later recalled.

While the negative role of Catholicism in the Dreyfus affair cannot be overstated, it is necessary to recognize those few Catholics who bravely supported Dreyfus, and who, in many cases, put their own reputations on the line. There existed a milieu of pro-Dreyfus and reform-minded Catholics in Lyon. It included Chaine, Pierre Jay, Fr. Joseph Brugerette, and others centered around the Lyonnais newspapers Le Salut Public and Demain and groups such as Paul Viollet’s Comité Catholique pour la Défense du Droit. This “Lyon School” of pro-Dreyfus Catholicism was characterized by Léon Sentupéry in Le Lyon Républicain as having a threefold commitment to “the religious teaching of the Church, opposition to every form of clericalism, and to . . . appeasement and reconciliation through progress and freedom.” This was the context in which Chaine’s defense of Dreyfus emerged.

Paul Viollet (1840–1914)

Chaine became involved in the Dreyfus Affair in 1902, when he published his Lettre d’un catholique lyonnais à un évêque sur l’affaire Dreyfus (“Letter from a Catholic of Lyon to a bishop on the Dreyfus affair”) in the Catholic periodical Justice Social. What caused him to enter the fray, he later recalled, was seeing the “mass of Catholics taking, so imprudently, so unjustly, sides with the accusers of this man”. He could not bear the constant “blather, absurdities, and non sequiturs” he heard from Catholics regarding Dreyfus. The goal of his letter, he wrote to Fr. Brugerette, was to tell “Catholics, as a Catholic [that] the religion of Christ does not oblige us to hate the Jews, to believe in Dreyfus’ guilt, [or] in the infallibility of military judges.”

The letter begins with self-accusation: “If Catholics are suffering [because of anti-clericalism] in our country, isn’t it somewhat because they have committed heavy faults?” In other words: can Catholics, after their conduct in the Dreyfus Affair, continue to point fingers and blame their enemies for all of their problems? Is not the wound self-inflicted to some extent? He continues by comparing the independent and critical spirit of Catholics in other countries (“particularly in Switzerland, Belgium and among the Catholics of the great American Republic”) to the “childish, narrow and sectarian nationalism” which led so many French Catholics to support the army over Dreyfus.

The core of Léon’s opposition to antisemitism, besides his belief in Dreyfus’s innocence, was a deeply evangelical conception of the church. According to Louis-Pierre Sardella, Chaine believed that French Catholics had “forgotten . . . the religious ideal of Christianity: love of peace, tolerance, justice.” They had, in his view, betrayed the very essence of the Gospel and the religion of Christ.

Militarism and Nationalism

Chaine did not limit himself to merely criticizing antisemitism within Catholic circles. He also spent many chapters in his book Les catholiques français et leurs difficultés actuelles (“French Catholics and their current difficulties”) attacking nationalism and militarism. Such critiques were absolutely necessary during a period of time when the antisemitic “integral nationalism” of Action Française was attracting many Catholics.

In the second chapter of his book, Chaine argues that militarism in effect enables a total reversal of the relationship between God and man. Instead of man being made in God’s image, God is shaped in man’s. “We have, in fact, invented the vengeful God, the jealous God, the God of battles,” he states, by attempting to attach God to our side and our country.

Chaine contrasts his view on war with that of the ultramontane and reactionary Catholic Joseph de Maistre, who “goes so far as to discover in [war] a divine law.” Gruesomely, de Maistre speaks of “the universal law of the violent destruction of living beings” and how “the whole earth, continually steeped in blood, is nothing but an immense altar on which every living thing must be sacrificed without end, without restraint, without respite until the consummation of the world”. In response to this, Chaine wittily quips: “if this is genius, [perhaps] the man who declared that genius borders on madness was not mistaken.” De Maistre’s view, to Chaine, was absolutely contrary to Christian principles—and borderline insane.

Chaine believed that Christian conscience absolutely condemned and abhorred “the execrable crimes committed by French people in Africa, in Madagascar, in China” and “all wars of conquest”. Chaine’s opposition to war emerged not only from a humanitarian impulse, but also from his unique conception of the church. War and nationalism were to be opposed by the church, since, in his view, the church was a “sublime International.” Likewise, Catholics were not required to believe in the exclusive nationalism of a “Catholic France” (“‘Catholic and French always’ . . . rings falsely in our ears,” he writes) but simply a peaceful patriotism that requires a Catholic to “[value] his status as a Catholic infinitely more than his nationality.”

Antisemitism, militarism, and nationalism: these three issues were not isolated for Léon Chaine. Rather, they were deeply connected. Ultimately, they were all rooted in a refusal on the part of French Catholics to be true to their evangelical beliefs, a refusal which led them to become narrow-minded and sectarian. Against this sectarianism, Chaine advocated for the broadness of the universal church to permeate the spirit of Catholics so that they might conform themselves more closely to the essence of their religion.

Conclusion: Contemporary Relevance

After anonymously publishing his last book, Ce qu’on a fait de l’Eglise (“What we have done with the church”), in 1912, Chaine ceased to write about Catholicism and spent the rest of his days devoting himself to his career as a lawyer. He died on Christmas Day in 1941 in Caluire, a suburb of Lyon. He was 90 years old.

Except for a short period of intense writing between 1902 and 1912 occasioned by the Dreyfus Affair, Chaine’s life was relatively uneventful. Nonetheless, the writings and witness he left us are profoundly valuable. They give us a glimpse into the world of Catholic liberals in the early 20th century who, despite being a minority, fought bravely against the social evils of their day.

Chaine should not remain a mere historical curiosity to us. We ought to take note of what the Dominican Vincent Maumus, a Dreyfusard priest, had to say about him in 1910: “if . . . all Catholics [during the Affair] had Mr. Chaine’s attitude, many disappointments, I believe, would have been spared them. This is already old history, the misfortune is that it continues.”

Can we not say that this history continues for us as well, in one form or another? We are seeing a resurgence of the errors of nationalism and antisemitism, both inside and outside the church. Chaine’s Christian witness against these evils has once again become increasingly relevant. His life and work show us that other paths remain open for Catholics. ♦

Gregory Fox is an independent researcher based in Virginia whose primary focus is the history of social, democratic, and liberal Catholicism in 19th- and 20th-century France.

-

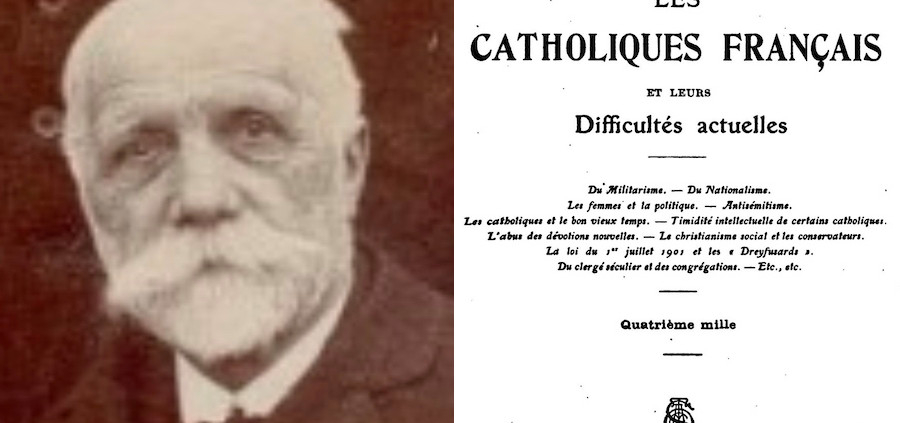

Top image: Léon Chaine / Title page of Les catholiques français et leurs difficultés actuelles, 1903 A. Storck edition

-

École Saint-Thomas d’Aquin-Veritas image credit: QCultureG | Wikimedia Commons | CC BY-SA 4.0

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!