A Vocation of Presence: On the Canonization of Charles de Foucauld

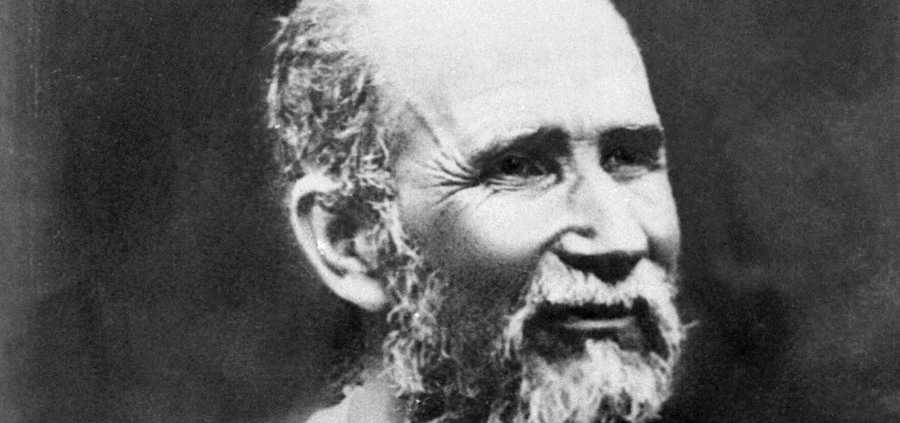

On May 15, Pope Francis canonized Blessed Charles de Foucauld along with six others. There are many good overviews of Foucauld’s life and witness available online, so I will not go into too much detail here; what I wish to focus on instead, and what seems to me to be the element of his vocation most beneficial to us today, was his call to imitate the hidden life of Christ in Nazareth.

In a time when the machinations of the neoliberal economic order have made everyone a market actor first and a person second, when pressure mounts to focus not on feeding one’s soul but building one’s brand, when even legitimate imaginings of a new and better and more just world can be captured by advertisers and reprocessed into slogans, willful anonymity becomes a countercultural act. To seek the good and to do it without expectation or hope of reward, even the reward of spiritual fellowship, counters the trend to make everything about ourselves.

This is what Foucauld did in his flight to Tamanrasset in Algeria on the edge of the Sahara, living as a hermit among the Tuareg people and ministering to them not as a priest or missionary but through a vocation of presence. He became the paradigm of the “other-centered” life; through his love for neighbor, he forgot himself in God. He learned the Tuareg language, offered Mass, food, medicine, and hospitality, and collected, translated, and anthologized Tuareg poetry. None of this was done with an end goal in sight. There was no plan for evangelization, no political initiative; there was simply a person opening himself to the process of continual conversion through encounter with others.

The road to Tamanrasset was a winding one, full of the kinds of false starts and detours that, when seen in the light of providence, are neither false nor detours at all. Foucauld spent time in the French army, joined and left the Trappists, worked as a handyman and gardener for a convent of Poor Clares in the Holy Land, and was ordained a priest in France. In 1901 he went to Morocco and tried to start a religious community there. Failing that, he went to Algeria and settled in Tamanrasset in 1905. He died a martyr in 1916, shot by one of a band of robbers who had infiltrated his hermitage.

From the moment of his spiritual maturity, the thread running through all these episodes of his life was a fundamental commitment to the hidden life of Christ. The image he took for his imitatio Christi was, fittingly, the one passed over in the Gospels: the 30 years Christ spent in Nazareth, a backwater town on the fringes of empire, before his public ministry. Here Christ was son, neighbor, friend, laborer in his father’s trade. Says one first-hand account of the Little Brothers of Jesus, the religious order inspired by Foucauld:

This call to imitate the life of Nazareth is the main characteristic of Charles de Foucauld’s vocation. But it was only gradually, as his life unfolded, that he came to perceive all the strands of his ideal: he lived them, one might say, before he thought of them, and one step at a time he achieved complete and admirable fulfillment during the years he spent in Tamanrasset.

To live the “strands of our ideals” before we think of them—how this resonates as a lesson for us today, when we are so inundated with crises to solve that it can be tempting to take refuge in analysis. Against this Foucauld shows us that we do not need to wait to become perfect people, nor have perfectly formulated solutions, before giving ourselves over in a spirit of charity and love. Solutions come in small, concrete actions built up over time, not through overarching systems idealized at a distance. One is reminded of how Dorothy Day used to say that the aim of the Catholic Worker was not to “solve poverty” but to enter into the lives of the poor and marginalized by sharing a meal or lending an ear and so reaffirm their dignity.

Outwardly, Foucauld’s life was a failure. He made no converts, attracted no followers to his proposed religious order, published nothing outside of a book on the geography of Morocco written prior to his conversion, and died in obscurity. Yet this failure, this foolishness in the eyes of the world, became the seed that bore fruit for subsequent generations. It is perhaps his greatest lesson. Our technocratic, data-driven, means-tested, results-oriented modern world does not deal well with the circuitous (to us) logic of the spiritual life that he and other saints exemplify; we feel that if we don’t see quantifiable change right away, our actions are pointless. Foucauld’s witness offers a corrective. He gives us the building blocks of a response to a time of overwhelming global catastrophe: the self-honesty of the hidden life in Christ, the elevation of one small gesture to a person in need, and the courage to love without fear. ♦

Michael Centore

Editor, Today’s American Catholic

Please get to know this amazing man.