The Unswerving Faith of a Christian Monarch by Michael Ford

The deep-rooted faith of Queen Elizabeth the Second, who was buried privately at Windsor Castle this week after a magnificent state funeral, was the underlying inspiration for her outstanding servant leadership.

Queen Elizabeth II at the U.S. Bicentennial, 1976

Before her body was interred on Monday evening in the King George VI memorial chapel, alongside her husband, parents, and sister, a committal at St. George’s Chapel, where she often worshipped, included the Russian Kontakion of the Departed. The Dean, the Rt Rev David Conner, spoke of the Queen’s “uncomplicated yet profound Christian faith” which had borne so much fruit, not only in unstinting service to the nation, commonwealth, and wider world, but also in kindness, concern, and reassuring care for her family, friends, and neighbors.

During this intimate and moving service, the Queen’s emblems of power—a crown, orb and scepter—were taken from the top of her coffin and placed on the altar, symbolizing the end of her reign.

Throughout the day, tens of thousands had lined the streets to watch military pageants before and after the funeral attended by more than 2,000 guests in Westminster Abbey, where her wedding and coronation had also taken place. The coffin was carried by guardsmen from the Queen’s Company, 1st Battalion Grenadier Guards.

The Queen once told the nation that Jesus Christ was “an anchor” in her life. In his sermon, the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Most Rev Justin Welby, said her example was set not through her position or ambition, but through whom she followed. Referring to the new King Charles the Third, he went on: “I know His Majesty shares the same faith and hope in Jesus Christ as his mother; the same sense of service and duty.”

Few leaders, he pointed out, receive the outpouring of love that had been witnessed in the capital in recent days. “People of loving service are rare in any walk of life. Leaders of loving service are still rarer. But in all cases, those who serve will be loved and remembered when those who cling to power and privileges are forgotten.”

Among the many world leaders listening intently was the Catholic US President Joe Biden. The Queen met 13 out of the last 14 presidents.

People of all religious and cultural backgrounds made up the congregation. Queen Elizabeth helped make the UK more tolerant of all Christian denominations and other faiths, so the procession naturally incorporated representatives of the Jewish, Muslim, Sikh, Hindu, Zoroastrian, Buddhist, Jain, and Baha’i communities. The chief rabbi commented on the beautiful sense of interfaith harmony under the arches.

The liturgy was simple and dignified, the choral music heavenly. The Scottish Catholic composer Sir James MacMillan wrote a new anthem, “Who Shall Separate Us,” especially for the occasion.

Prayers were offered by members of various Christian traditions, the Roman Catholic Church represented by Cardinal Vincent Nichols, Archbishop of Westminster. In 1995, the Queen had become the first British monarch in 400 years to be present at a Roman Catholic service in her own country, attending vespers for the centenary of Westminster Cathedral.

The Queen also met five different popes, including Pope Francis, who recently praised her “steadfast witness of faith in Jesus Christ.” She was admired at the Vatican.

Elizabeth the Second died on Thursday, September 8, at her Scottish retreat, Balmoral Castle. Within hours, a devout British Muslim was standing outside her home, Buckingham Palace, mourning the death of his monarch. “I said my prayers tonight and then I said one for the Queen,” he remarked.

From noon on the Friday, church and cathedral bells rang out across the land, and the doors stayed open for prayer. That evening, a national service of reflection was held at St. Paul’s Cathedral. The next morning the Accession Council met to formally proclaim Charles as the new sovereign. On Sunday, September 11, the Queen’s coffin made a six-hour journey through autumnal countryside from Balmoral to the Palace of Holyroodhouse in Edinburgh, where it rested overnight before a service and lying-in-state at St. Giles’ Cathedral.

After being flown to an airport on the outskirts of London, the coffin was taken to Buckingham Palace and the following day began a ceremonious journey by horse carriage to Westminster Hall, the oldest building on the parliamentary estate, for a formal lying-in-state over several days.

Transport of the Queen’s coffin to Westminster Hall. Photo by Michael Ford

As I stood for hours among the chattering crowds in the flag-lined Mall that afternoon, I found myself acutely aware that each of us was not so much watching history as taking part in it. The long stretch of road, with crowns perched on top of posts, was swept continually by a cleaning truck. The mood was convivial at first, not so dissimilar from the wedding of Harry and Meghan which I’d witnessed in Windsor four years before.

The warm sun began to pierce through the passing clouds and, sandwiched in though we were, people had brought along picnics with a predilection for Italian macaroons. Strangers got to know each other a little, and there was occasional reflection on the Queen’s deteriorating health in recent months.

Then, as soon as gun fire was heard at precisely 2:22 p.m., the atmosphere changed at the drop of a busby. To the strains of Beethoven’s Funeral March no. 1, the solemn procession with troopers of the Household Cavalry set off, with the Queen’s four children and other members of the Royal Family walking in mournful dignity behind the cortege. It called to mind “A Prayer for the Queen’s Majesty” from The Book of Common Prayer, which ends with the hope that “finally after this life she may obtain everlasting joy and felicity.”

The Queen was like a mother to the nation—our longest-reigning monarch for over 70 years and the second-longest in world history, surpassed only by Louis XIV of France. I couldn’t help recalling the few times I had seen her, most memorably at Dunblane in Scotland after 16 schoolchildren and a teacher had been killed by a gunman. She and Princess Anne went to offer comfort to grieving families and a distraught community. It remains the deadliest mass shooting in British history.

The United Kingdom has a constitutional monarchy which means that, while the sovereign is head of state, the ability to make and pass legislation rests with an elected parliament. Although Queen Elizabeth did not have a political or executive role, she played a pivotal part in the life of the nation by undertaking endless constitutional and representational duties developed over one thousand years of history. She was a focus for national identity, unity, and pride, giving always a sense of stability and continuity. She officially recognized success and excellence through the bestowing of awards (as well as cards for 100th birthdays) and earnestly advocated the ideals of voluntary service. In all these roles, she was supported by members of her immediate family.

The Queen had a strong sense of duty and a determination to dedicate her life to her throne and her people. She became for many the one constant in a rapidly changing world, which is why some treasure photographs, spoons, and commemorative mugs of her in their homes. And, of course, she’s on our postage stamps and bank notes.

Elizabeth the Second combined personal charisma and professional distance to ensure that the monarchy survived and had a reason to exist. Over two-thirds of people in the UK support the continuation of the monarchy, but there are undoubtedly republicans, some of whom have been protesting in recent days, although I didn’t hear any myself—just reverence for Her Majesty.

When the procession on Wednesday, September 14, finally reached Westminster Hall, a choir sang Psalm 139 (“O Lord Thou Hast Searched Me Out”) before a short service. Then, over several days, silent vigils, which were televised, were kept around the catafalque, at times attended by the Queen’s children and grandchildren.

In this effusion of genuine grief, affection, and gratitude, a quarter of a million people travelled from all over the UK and beyond to walk beside her coffin. At one point the queue stretched for 10 miles along the River Thames. The longest waiting time was over 24 hours. Thousands stood in the rain and cold all night so they could silently bow, kneel, curtsey, or make the sign of the cross. Both sadness and respect were etched into their tired faces.

The British Catholic academic, Professor Simon Lee, a former student at Yale Law School, Connecticut, queued for nine hours before reluctantly deciding to return home. He pointed out that English Catholics were very much part of the national mourning. “Those who are serious about their own religious faith appeal to us, especially those who wear their faith lightly but act on it to make a difference in the world, like Queen Elizabeth,” he told me.

Professor Lee once sat next to the Queen at a Buckingham Palace lunch in the light of his involvement in bringing Catholics and Protestants together in Northern Ireland. “The Queen asked if I thought there would be a ceasefire that year, which I did—and there was. She said she had been struck on her last visit to Northern Ireland how much the families of prison officers yearned for peace. She too knew what people were thinking at grassroots level.”

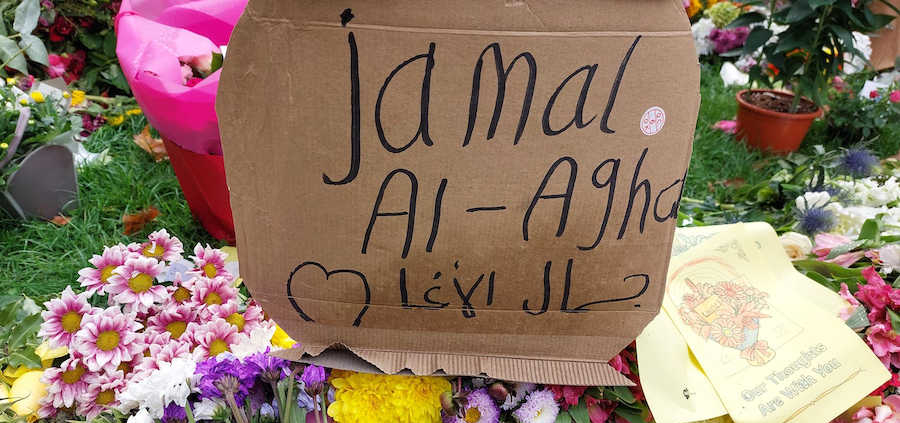

On two occasions, I meandered among the blankets of floral tributes spread over Green Park near Buckingham Palace. Smaller bunches were placed around trunks. The messages were deeply touching. One of the first that caught my eye read: “Elizabeth R. In loving memory and with our thanks. Recognising and admiring the integrity, values and unswerving sense of duty you have brought to seven decades of service on behalf of our country and the Commonwealth. You became the ‘glue’ which held our divided nation and brought together in unity the nations of the Commonwealth.”

Another stated that the Queen had given all men and women around the world the perfect role model of selfless dedication with dignity, unconditional love, and elegance: “Your father King George VI would have been very proud of you, as you exceeded more than what he could have ever imagined.”

Mother and daughter, Farah and Kiana Crawford, from Utah, join crowds in Green Park to honor the Queen. Photo by Michael Ford

After becoming Queen on his death, Elizabeth II dutifully embraced her regal obligations as a divine vocation. In the Christmas message before her coronation in 1953, she asked that people should pray “that God may give me wisdom and strength to carry out the solemn promises I shall be making and that I may faithfully serve him and you all the days of my life.”

That day, when the Queen had entered the abbey, she had instinctively walked past the throne on which she would sit and by herself knelt in prayer at the high altar. “There’s a profound symbolism there of the Head of State giving her allegiance to God before anyone gives their allegiance to her,” Archbishop Welby observed.

The Queen was Defender of the Faith and Supreme Governor of the Church of England. But it was Christianity, rather than Anglicanism per se, which she increasingly spoke about in her Christmas Day broadcasts, traditionally watched at 3:00 p.m. on December 25 after a hearty lunch.

In the year 2000, when she read a blessing from her own prayer book, the Queen told viewers: “To many of us our beliefs are of fundamental importance. For me the teachings of Christ and my own personal accountability before God provide a framework in which I try to lead my life. I, like so many of you, have drawn great comfort in difficult times from Christ’s words and example.”

Following the 9/11 attacks in 2001, the Queen (who visited more than two dozen cities in the United States) stressed the importance of faith in guiding people and the need to have hope in a better future. “It is to the Church that we turn to give meaning to these moments of intense human experience through prayer, symbol and ceremony. In these circumstances so many of us, whatever our religion, need our faith more than ever to sustain and guide us.”

In 2014, the Queen was more personally explicit, some might say even a touch evangelistic: “For me, the life of Jesus Christ, the Prince of Peace, whose birth we celebrate today, is an inspiration and an anchor in my life. A role model of reconciliation and forgiveness, he stretched out his hands in love, acceptance and healing. Christ’s example has taught me to seek to respect and value all people, of whatever faith or none.”

Then, on Holy Saturday 2020, when churches were closed because of the coronavirus pandemic, the Queen attracted a large audience of viewers, anxiously looking for some reassurance: “The discovery of the risen Christ on the first Easter Day gave his followers new hope and fresh purpose, and we can all take heart from this. We know that coronavirus will not overcome us. As dark as death can be—particularly for those suffering with grief—light and life are greater. May the living flame of the Easter hope be a steady guide as we face the future.”

These are words which console us now as we mourn the loss of a unique sovereign, a true Christian monarch who, though a global public figure, remained private and humble to the end. In a rare foreword to a book a few years ago, she wrote that she was “very grateful” to God for his “steadfast” love. “I have indeed seen His faithfulness,” she said. ♦

Michael Ford is a biographical writer and ecumenical theologian living in the UK. His features for TAC reflect a lifelong interest in the spiritual and psychological journeys of women and men from all walks of life. He may be contacted at hermitagewithin@gmail.com.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!