Spiritual Awakening on the Holy Mountain by Michael Ford

Addiction has become one of the most disturbing social disorders of our time. But it’s important to remember that the psychological, neurological, and spiritual dynamics of full-blown addiction are at work in each human being, according to the Christian psychiatrist Gerald May. The same processes accountable for addiction to narcotics and alcohol are also responsible for addictive ideas, work patterns, relationships, power crazes, fame obsessions, and fantasies of every imaginable kind.

It is a sobering thought.

Although addictions form part and parcel of how we operate—including contemporary obsessions with gaming and smartphones—they are also our own worst enemies. They enslave us with chains of our own making and yet are virtually beyond our control. Addictions make idolaters of us all, argues May, because they compel us to worship the objects to which we are fatally attached.

Statistics in the United States make for uneasy reading: Among people aged 12 or older in 2020, 37.3 million had used an illicit drug, according to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. And the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that there have been 932,000 drug overdose deaths since 1999.

One of the most high-profile fatalities was that of the New York actor and director Philip Seymour Hoffman, who lost his life suddenly at the age of 46. Hoffman, who was raised a Catholic, had engaged in drug and alcohol misuse while a student at New York University, later acknowledging he had taken “anything I could get my hands on. I liked it all.” Following his graduation, he entered a drug rehabilitation program and then remained sober for 23 years.

However, the Oscar-winning actor, acclaimed for his riveting performances of profound intensity, relapsed in 2013 and admitted himself to a drug rehabilitation center for a short spell. But in February 2014, he was found dead in the bathroom of his Manhattan apartment. Detectives came across heroin and prescription medication, and revealed he had a syringe in his arm.

Hoffman’s death was officially ruled an accident, caused by “acute mixed drug intoxication including heroin, cocaine, benzodiazepines and amphetamine.” It was never reported whether he had taken all the substances on the same day or whether any had remained in his system from earlier use.

People living with addictions often need safe havens and nonjudgmental care for longer than they might realize. But substance use and mental health issues can undermine a person’s ability to access compassionate, high-quality facilities.

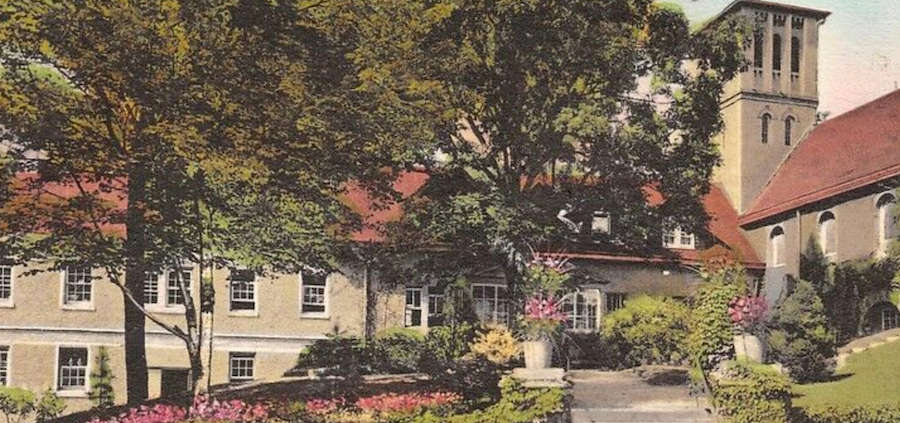

Fifty miles north of New York City, in the peace and beauty of the Hudson Valley at Garrison, lies St. Christopher’s Inn, a treatment center for men seeking rehabilitation from substance abuse and alcohol addiction.

Run by the Franciscan Friars of the Atonement, it was founded in 1909 and was once a temporary shelter for the homeless. The Inn is different from every other addiction treatment center because the men live in the home of the friars at Graymoor. Known as the “Holy Mountain,” Graymoor is, in fact, the birthplace of the Week of Prayer for Christian Unity (January 18–25), which was started by the Friars and Sisters of the Atonement.

The men who arrive at St. Christopher’s Inn usually stay for between 80 and 90 days. Their range of disorders include addiction to opiates, alcohol, and methadone. Depression, anxiety, trauma-related experience, and bipolar disorder increasingly accompany and exacerbate their problems.

In keeping with the ideals and philosophy of St. Francis, the Inn offers free accommodation to all incoming patients. Most outpatient clients live in the shelter free of charge while undergoing their treatment, a suitable option for male substance abuse victims unable to afford the high costs of treatment.

Elements of Franciscan spirituality permeate the treatment program, and there is a constant awareness of the power of grace. The words of St. Francis underpin the program’s mission: “We have been called to heal wounds, to unite what has fallen apart and to bring home those who have lost their way.”

As Father Dennis Polanco, president and spiritual director, puts it: “Frequently the men feel they are broken beyond repair because one of the first things that the disease of addiction weakens or destroys is a person’s spirit. They lose hope of ever recovering and need a spiritual awakening.

“All the staff help to heal the wounded spirits of our brothers who come to us. First of all, our medical team attends to the healing of their bodies through adequate sleep, good food, and individual exercise. Next comes a clearing of their minds as they begin to pay attention to themselves and the way they perceive the world around them. Counseling helps the men get rid of cognitive distortions and negative thinking. Spiritual counselling by the friars and trained spiritual directors addresses issues of shame and self-forgiveness. All the men care for the upkeep of their home at the Inn. This restores a sense of pride in their work and gives them a good feeling of accomplishment, even learning new skills. This combined effort is essential in the recovery process.

“In each man who comes for shelter or treatment, we see the suffering Christ. Everyone who comes to us is a ‘Brother Christopher’ in that they represent the Lord seeking us. Our mission is inspired by the words in chapter 25 of St. Matthew’s Gospel (‘For I was hungry and you gave me food . . .’).”

Many of the Brothers Christopher have no idea at all about “spirituality” as such, but during their time at the Inn they learn that they have been created in the image of God (or their “Higher Power”) and rediscover the human spirit of forgiveness, peace, goodness and joy. Sobriety, they come to appreciate, is the concrete gift of God or their “Higher Power,” a daily reprieve from substance use.

“The Word of God inspires many of the men who choose to come to our church services,” Father Dennis explains. “Relating the Sunday and daily readings to the 12-Step programs helps the men see how both are very much connected. They are asked to consider how they stand each day in relation to God or their ‘Higher Power,’ their brothers, and themselves. Meditation is introduced as a way of being in conscious contact with God or their ‘Higher Power.’ At first, many are uncomfortable with 15 minutes of meditation at the end of the day (all led by the men themselves), but they grow to enjoy this peaceful time. Joy in suffering is also experienced. They discover that sobriety can be fun as they take part in outdoor games, exercise or playing chess, dominoes and ping-pong.

“Our brothers comment so many times on the fact that something has changed, but they don’t know how. They often experience many ‘coincidences’ that they never paid attention to before, and they interpret these as signs of God or their ‘Higher Power’ walking with them in their lives. Our chapel services are optional since we welcome men with faith as well as those who say they have none. But here the men rediscover their relationship with God, something that had seemed occluded through the use of substances. From the onset, addiction takes away spirituality.”

Father Dennis explained that many men seemed to relate well to the “Seven Spiritual Needs” (the spiritual hungers all people have in common) drawn up by the pastor and psychological counsellor Howard Clinebell. Clinebell based his approach on the belief that human beings long to experience the healing and empowerment of love from others, themselves, and an ultimate source. This includes renewing times of transcendence, those expansive moments beyond the immediate sensory spheres.

The men who work with Clinebell’s teachings learn to cultivate vital beliefs that lend meaning and hope in the midst of losses, tragedies, and failures; they develop values, priorities, and life commitments centered on issues of justice, integrity, and love in order to move towards responsible living; they discover and develop inner wisdom, creativity, and love of self; they gain a deepening awareness of oneness with other people, the natural world, and all living things; they acquire spiritual resources to help heal grief, guilt, resentment, unforgiveness, self-rejection, and shame; and they broaden experiences of trust, self-esteem, hope, joy, and love of life.

“I have discovered over time that this is a great place to start in introducing ‘spirituality’ to most of the men,” Father Dennis elaborated. “Even those who have been raised with a community of faith soon discover the richness that already dwells within; they just need a guide to help them discover what’s already there. This, to me, is the ‘grace’ of God or ‘Higher Power’ dwelling in all of us as images of our Creator.”

The Brothers Christopher are wounded healers who reach out to all the new arrivals at the Inn, sharing their experiences, strength, and hope and seeing in the newcomers a gift for their own sobriety. This is a key component in all 12-Step programs: Tradition 1 (each “Tradition” is a counterpart to one of the 12 Steps) of Alcoholics Anonymous says: “Our common welfare should come first; personal recovery depends upon AA (Alcoholics Anonymous) unity.” Step 12 states: “Having had a spiritual awakening as the result of these steps, we tried to carry this message to alcoholics, and to practice these principles in all our affairs.”

By sharing their backgrounds, progress, and vision at every meeting, the men bring reassurance to others. The telling of stories of pain and loss gives encouragement and insight to all in recovery. In the common meeting room, they can’t miss a quotation in large letters: “I am a good man, worthy of love and respect.” In lectures and small groups, staff underline the same message.

For Roman Catholic brothers, the sacrament of reconciliation is available on a weekly basis but not forced. “This experience of forgiveness brings such great peace and relief to so many of our brothers,” said Father Dennis. “In spiritual direction, they often tell me about their experiences, rather than their sins. During Covid-19, isolation was the biggest challenge, with the men not being able to meet together physically in 12-Step meetings. This has been overcome somewhat with the use of modern technology, including Telepractice and Zoom, for 12-Step meetings, counselling sessions, and even medical and psychological care. It doesn’t replace human contact but takes away the sense of being alone which can trigger the use of substances.”

But there are still daily challenges. For example, some younger men in their 20s and 30s simply aren’t ready for the work of recovery. “Just last week, two men in this age group ended up overdosing and dying so very young,” said Father Dennis. “Counsellors and staff tell everyone they are in a fight for their lives. Deaths from overdoses increased during the pandemic.”

Several years ago, staff came to terms with failure and decided to honor with a brick memorial any Brother Christopher who passed away. The bricks with names now form a sacred space at the entrance to the Inn. They also remember the living: those staff, friars, and benefactors who have generously supported them over the years.

The friars’ ministry to chemically dependent men in crisis is extended to their families and all those they love. Testimonials bear witness to the Inn’s effective ministry of compassion. “After years of failed attempts at sobriety and the loss of everything and everyone I cared for, my life seemed over,” wrote one man. “St. Christopher’s Inn saved my life; gave me new purpose.” Another commented: “The love, respect, and spirituality given to me there has renewed my faith in God. I am reborn.”

Such remarks bear out the insights of psychiatrist Gerald May: “Our addictions can lead us to a deep appreciation of grace. They can bring us to our knees.” ♦

Michael Ford is a biographical writer and ecumenical theologian living in the UK. His features for TAC reflect a lifelong interest in the spiritual and psychological journeys of women and men from all walks of life. He may be contacted at hermitagewithin@gmail.com.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!